The exhibition at ‘O’ Art Space, Lahore in the memory of Qutub Rind, which included works of other artists, evoked new insights into his work

As there are various words for death in different languages, there are numerous modes of dying. Qutub Rind died in an unjust manner. In July this year, he had an argument with his landlord over a minor matter related to non-payment of rent. The landlord and his brother allegedly beat him with a rod and pushed him down the stairs from the third floor of the house. The sudden death of the 34-year-old artist was as shocking and disconcerting as the way his murder was manipulated, initially by the man who killed him, and then by others on social media. In order to justify his action, the murderer falsely accused him of blasphemy.

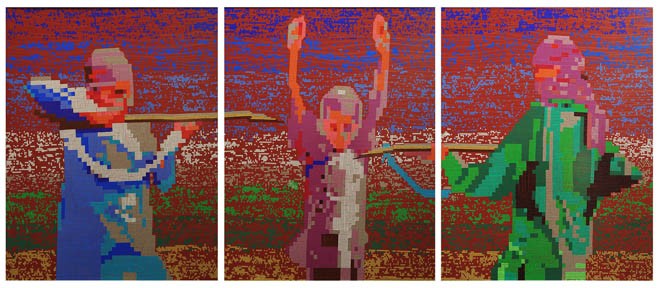

The case of Rind is an example of how reality is misconstrued and misconstructed. In an ironic scheme, the blinding of facts for certain gains is echoed in the aesthetics of the artist. Rind graduated in Fine Art, specialising in Miniature Painting from National College of Arts, Lahore in 2014. During his last year at the college, he evolved a style for representing his subjects: groups of people, guns, grenades, single figures and portraits were all rendered with round pieces of reflective tape of varying hues. Shifting the size of his basic unit, changing the chromatic order -- from strong to subtle -- he transformed a definite reality into a diffused picture. Looking at his works derived from actual references, one joins bits of visual information and arrives at a conclusion -- but not a clear one.

This is exactly what happened to him. With hindsight, one can view his work which, in a sense, foretold his death (he mostly depicted weapons). It was strange experience seeing a large body of his art work at the exhibition in ‘O’ Art Space, Lahore from October 12-22, 2018 which included works of other artists. It was something like an encounter in purgatory. One look at the artwork hung in different sections of the gallery was enough to bring back his personality; reading the titles from the exhibit list revived his voice. Trying to trace his formal development through works created from 2010 to 2018, his words resonated, explaining what he had created during class critiques at NCA.

For me, in his death there is a personal link and perpetual feeling of loss. As someone who saw him as a boy from Jacobabad to becoming a refined student (he was awarded distinction on his final year project), the exhibition dedicated to his memory evoked many questions. Foremost was how and why a work, or our perception about it, changes if we know the artist is no more. This is not particular to visual arts, but in other fields of creative expression too, death brings out different responses. In the case of some writers like V. S. Naipaul, Philip Roth and Gunter Grass, death makes a reader revert to their books, hence reprints of novels and short stories.

The situation is different for writers and artists. Even though a poet or prose writer earns from his words, yet his text is not owned by a single individual, nor does the passage of time increase or reduce its worth. Often in someone’s possession, the price of a work of art depends on the age, health or death of the artist. The hype in monetary value of an art work can be compared to the rise in the dead artist’s aesthetic worth. Death sometimes enhances interest in an artist. Imagine the possibility of Asim Butt’s retrospective at the Mohatta Palace Museum, Karachi in 2011 if he had not committed suicide at the age of 32. The exhibition organised for Qutub Rind made the viewers see his work in a new light. One discovered that it was not only the technique of the artist, translating regular photographs and items into circles, but his choice of colours and his combination of loud and muted shades that made his art distinct. A series of works showing rifles in identical scale reflects the artist’s sophistication in his pictorial language. Although it reminds one of Shahbaz Malik (another painter who picked an unusual pictorial vocabulary), Rind appeared more natural, intuitive, and abrupt.

As it so happens one does not pay much heed to a person’s utterances in their life, but start pondering, understanding and reviving them only after they are no more. The preference of Qutub Rind for guns, bullets, grenades, and other violent imagery was considered ‘normal’ due to his background and fascination. Rind talked about his work that "deals with the idea of altering the context of violent tools with aesthetically beautiful and harmless objects such as beads/moti". However, it is only after his murder, that one perceives a pistol with bullets coming out (‘Untitled’, 2014), two rifles in a diptych (‘Positive Negative’, 2016) a machine gun with a fully-loaded magazine (‘Tangawe’, 2016), and several characters holding guns and posing as if for a formal photograph as snapshots of a grief that was envisaged.

The violent death of Rind has introduced new meanings to these visuals, revealing how aggression, anger, and weaponry have become so much a part of our existence. At the same time, the fact that all these tools of power are not able to defend a human being, an artist, a person drawing inspiration from his background, is a comment on the condition of a society that failed to save him.

Even though artists were unable to secure his life, they could help his family, as was felt by coming across works of other artists such as R.M. Naeem, Muhammad Zeeshan, Ali Kazim, Adeel uz Zafar and many more. Besides this obvious good cause, promoting, protecting and defending art from different parts of Pakistan could be a means to make diversity of ideas, strategies, regions and training an essential and indispensable part of the mainstream. One wishes that all those artists, including some of the most well-known names and his friends who have supported Rind through their works, can keep doing this by finding other Rinds in our midst, and not letting them die, physically or otherwise.