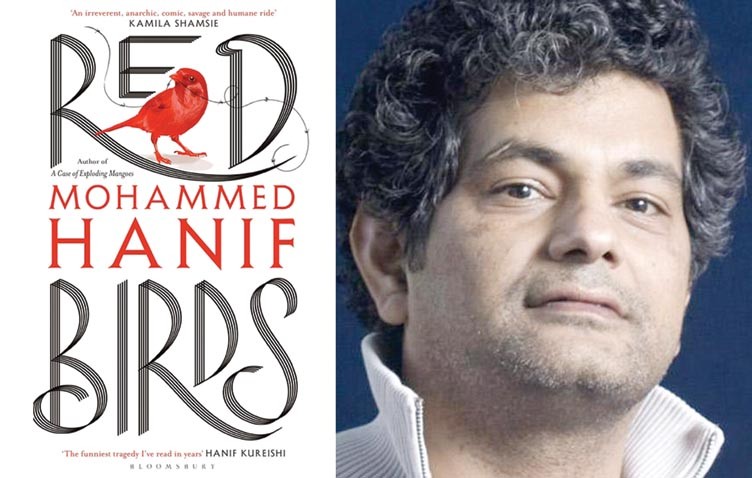

A satire depicting war and its accompanying perils through the biting humour and gripping language of Mohammed Hanif

All good, sensitive writers struggle with balancing humility on one hand and narcissism on the other. Both elements are crucial. A right amount of self-admiration allows a writer to break free of self-doubt and fear to push boundaries, and rejuvenate language. A sense of humility guides the writer to entrust freedom to her characters, who are an extension of the writer and are thus in danger of sounding alike by default. The modern novel, in Mikhail Bakhtin’s view, derives its supremacy to other literary forms from a phenomenon called heteroglossia, wherein various language registers of the characters, narrators and of the author travel around each other in harmony and disruption. Now let’s turn to Red Birds by Mohammed Hanif.

Is it an anti-war novel? A critique of the American empire, capitalism-fuelled wars? Native complicity? Perhaps, a bit of all.

Three characters dominate the narrative: Ellie, Momo, and Mutt, who share the space, every third chapter, two-thirds of the novel. It opens with Ellie’s plane crashing into the Rigestan desert, near a refugee encampment. This is the exact encampment where Momo and his dog Mutt survive the war and its aftermath. In close proximity lies a non-operational Hangar, which has served the American forces’ military needs and provided employment to locals who helped with the occupation. The locals include Momo’s Father Dear, a tragicomic spineless figure, whose elder son Ali disappeared after he began helping the American forces find targets to bomb. Ellie is rescued and made prisoner by Momo as he goes into the desert searching for his dog, Mutt, whom he has injured earlier in a fit of rage. It’s a love and hate relationship between Mutt the dog and Momo, who hopes to get his brother Ali back to their mother by trading the prisoner Ellie at some point. Father Dear, in the meantime, has brought to their makeshift abode a researcher, Lady Flowerbody, to study the wars’ effects on ‘young Muslim minds’, a swipe Hanif takes on the neocons, the Raphael Patais and Bernard Lewises of the western world.

The concept behind the title Red Birds ties the first two and the last part of the story. The last drop of blood, as it pours out of the body of a casualty of war, flies away turning into a red bird. And there one occasionally sees red birds under certain circumstances; the stretch from flying red birds to ghosts is a short walk. There’s a subtle suggestion that by the time Momo rescues Ellie, the US pilot has already met his Creator. So it is possible what he brings home to his mother’s annoyance is a ghost. It is also possible that even Mutt has become a ghost, that is if Ellie had succeeded in killing it.

The only way to enter the Hangar is to have a white man upfront and once Momo’s team -- which includes his father and mother with a special dagger made of salt, the dog, even Lady Flowerbody -- arrives, a Star Wars of sorts takes place inside the Hangar between the good guys and bad guys. We finally get to meet Ellie’s mentor Col. Slatter, who seems to have been modelled after a mixture of Capt Kurtz and Brig. Gen. Jack D Ripper.

In the end, though it’s a victory, it seems Momo has retrieved Ali’s ghost or his sleeping body, and as the mother receives her son and then lies down beside him, one is confronted with the image of Pieta, mother Mary holding the dead body of her son, Jesus. And it is perhaps this connection at the back of Hanif’s mind that makes a beautifully poignant sentence possible, from Mutt’s point of view: "She pours tears in her curry, so sad is that woman. Why does she need salt, she could just cook with her tears?"

Hanif is fundamentally a humour writer, a practitioner of satire. To bomb or not to bomb becomes "To B or not to B", evoking Shakespeare. My favourite was Mutt’s description of Momo’s anger at his failed business plans: "And he kicks the ball so hard, and straight to the sky, that it disappears for a long time and only comes back to the earth when everybody has forgotten that there was a ball kicked towards the sky. It always comes back . . ." Of the three, Mutt the dog is the most ponderous; he seems well-aware of the fact that the day his brains got fried, he "became a philosopher . . ."

I think the best part of the novel is that Hanif, despite the apparent political agenda, humanises Ellie and Mutt the dog. Ellie and Ali (the missing son) are two sides of the same coin, doing empire’s bidding for different reasons.

Yet despite the novel’s complex emotional cartography, it fails to evoke emotion and lacks rasa (essence). Chapter after chapter dripping with dollops of acerbic wisdom, camouflaged political rants, and compulsive smart-aleckries, consuming most characters most of the time, weaken the novel. This reviewer feels that Hanif is aware of this on a subconscious level, as on page 182, while commenting on Momo, Ellie says that there "is nothing more irritating than cocky fifteen-year-olds", which could be Hanif’s way of commenting on the tone of the novel. Even the combined effect of all the narrators of Red Birds, sadly, do not translate into Holden Caulfied’s cynicism.

Disrupting a delicate balance, most characters begin to sound similar because they end up echoing the author’s rage and insight, thus obliterating heteroglossia to a large extent. The dog’s philosophic outlook notwithstanding, Mutt’s comments strain credulity when he utters "slashing milk money for poor babies at home" or "That is not how distribution of wealth works in post-war economies", while this is the same dog, who in a moment of innocence and honesty, admits that "I’ve never understood how money works"."

Although Hanif exhibits great command over American idiom and speech, while looking into Ellie’s head he doesn’t go beyond Ellie’s relationship with his wife, Cath. A soldier whose plane crashed and is about to die, or to be taken prisoner, or become a ghost would want to think of his mother and father, friends and other relatives too. The reviewer is stuck with a feeling that the novel is following a careful template and does not allow an organic growth of the narrative and of character. Finally, it seems, that the inclusion of a single cell phone could destabilise the entire novel. Even if the Americans have left, there are a lot of people still present in the camp, not to mention the woman doing her research on the ‘young Muslim mind’, who must have some contact with the outside world. There’s no imminent danger of famine there. Even if all of them are ghosts, including Ellie and the researcher, why can’t someone have a phone when they can have Jeep Cherokee and guns and food?

However, in retrospect, these are minor shortcomings. Hanif’s biting humour and crisp language keep a tight grip on the flow of the novel. Thankfully most chapters are short, discouraging the reader from losing interest. The novel offers a critique of American behaviour from a non-western point of view, and gives the American reader some food for thought.

Red Birds [Hard Cover]

Author: Mohammed Hanif

Publisher: Bloomsbury India

Pages: 320

Price: Rs1,145