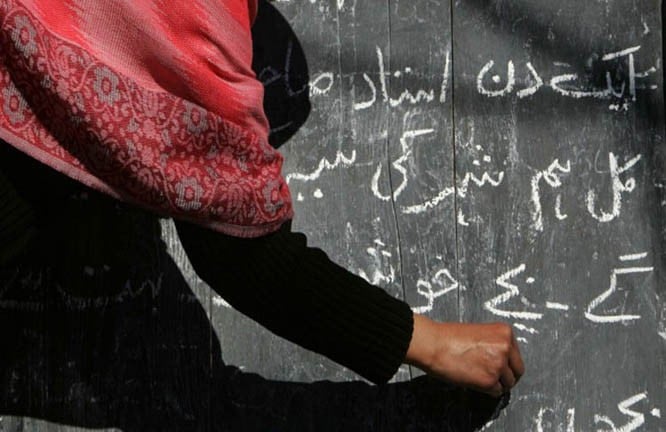

Teaching and learning Urdu at a time when English has a hegemonic hold on the world’s imagination

Nahin khel aye Daagh yaaron say keh do

Keh aati hai Urdu zubaan aatay aatay

Each morning in Lahore, Sadia Sarmad checks feedback on her uploaded Urdu audio stories for children, arranges meetings with her volunteers for fresh ones and then proceeds to the recording of ones already in progress. Intermingled with these is her ongoing search for new ideas, supervising write-ups and finding quality voices for recording. These activities contribute to her project Suno Kahani Meri Zabani, a labour of love for Urdu.

"I have been reading and telling stories to my children since they were babies," shares Sadia. "As they grew older, I started playing audio stories for them while I drove them home from school, but unfortunately, I could find such stories only in English. Hence, I came up with the idea of recording moralistic audio stories in Urdu, to facilitate parent and child communication and to build a better and stronger relationship between them."

With a background in graphic designing, Sadia, also a story teller and reciter, pursues her passion entirely on a voluntary basis, with famous names like TV artiste Bigul Hussain, writer Saji Gul and Dr. Ahmed Bilal, a PhD holder in filmmaking, supporting the project. She believes her cause is more important than the mere pursuit of money, and will help promote a love for Urdu in the next generation.

"Unfortunately, parents have been brainwashed with the concept that Urdu is the language of the have-nots. Plus, it is now portrayed as a difficult language, so it is ignored despite being an amalgamation of different languages," says Sadia.

Sadia’s project of audio stories reminds me of Kassette Kahani -- a series of Urdu stories on tape which I as a child used to love listening to. A production of EMI, Kassette Kahani was a collection of famous fairy tales like Cinderella, Jack and the Beanstalk, Red Riding Hood and the Arabian Nights stories in Urdu. Complete with background music and audio effects, the narrations would always carry me to a magical world of stories.

I faced the same dilemma as Sadia Sarmad, when wanting to share this wonderful journey with my own children. I discovered that since our time audio tapes have become obsolete, along with Kassette Kahani, and there is no back-up or modern version. Although while researching for this article, I did come across a Facebook page of Kassette Kahani, it is largely unknown and includes only bits and pieces from the original series, not enough to have the profound effect it once had.

It’s not just technological advancement which led to these series going obsolete. While the demise of Kassette Kahani owes largely to piracy, with the original team not being able to fight pirated versions and thus forced to abandon the project, a lack of fluency in the national language of Pakistan among all classes, particularly among the urban upper classes, is leading to disinterest in Urdu fiction.

Urdu’s usage has decreased drastically in educational institutions. Those that proclaim a relatively better standard officially communicate in English with both employees and students. All subjects are taught in English except Urdu itself. This is in stark contrast to the time Pakistan came into existence.

"Uss waqt Urdu parhanay ka mayaar behtar tha (At that time the standard of teaching Urdu was better)," reminisces Sabuha Khan, an author in Urdu who also happened to be a secondary school teacher as well as an Urdu newscaster at PTV during the 1970s. "Poori tawajoh say parhaatay thay, mehnat kartay thay (we worked really hard to teach and with full concentration)."

Today, the emphasis on creative and innovative teaching methods seems limited to subjects which are taught in English. For these subjects, teaching workshops and training methods are shared extensively with teachers. In preschool in particular, where students are introduced to letters of the alphabet and beginning of language structures, catchy tunes, arts and crafts and videos usually accompany lessons.

But such techniques remain conspicuously missing in Urdu. In most schools, a group of Urdu teachers headed by a senior instructor gets together and discusses teaching methods in its planning meetings and creativity in Urdu classes is dependent upon that of the teacher. Audio-visual aids remain limited to flash cards. Students often bring back crafts announcing the introduction of a new shape, colour or number of the English alphabet but rarely do the same for Urdu. Story telling sessions in schools are also mostly in English.

Hence the focus to excel also remains in English. Many parents belonging to middle class households in Pakistan have now switched to conversing in English with their children, which promotes the idea that Urdu is a language relegated to those who haven’t made it.

In his book Crimson Papers, poet and essayist Harris Khalique narrates a story famed Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz told his father, filmmaker Khalique Ibrahim Khalique. After dinner at a senior Pakistani diplomat’s residence in Delhi, the diplomat’s son asked Faiz for an autograph. Faiz inscribed one of his verses and put his signature. The boy looked at his autograph book in amazement and told Faiz that he knew such good English and his father had told him that Faiz was also the editor of a leading English newspaper, but he had given him the autograph in their cook’s language.

What may have led to this abandonment of Urdu?

"It’s the legacy of our colonial past," says Tamania Jafri, a Canadian-Pakistani, who runs a blog by the name of urdumom.com solely for the purpose of promoting learning in Urdu.

A desire to succeed across borders also goads people to be fluent in English, the lingua franca of the world. Jafri quoted a research survey conducted in Canada, which revealed that most Canadian-Pakistani parents give preference to the learning of at least 3 other languages over Urdu. First is English, the second is French since Canada is a bilingual country and third is mostly Arabic, since parents want their children to recite and understand the Quran.

To save the declining status of Urdu, some sincere efforts seem to have begun. Improved quality of publishing and visuals is now occasionally seen in storybooks for children, which some time back, seemed to be on the verge of extinction. Oxford University Press, Ferozsons Publishers and Book Group are doing significant work to this end.

While the emphasis is more on the very young -- children aged between 3 to 8 years, lesser variety is available for older groups, especially teenagers. The only choice available is a throwback to yesteryears, when Urdu fiction-reading among the young was also common. Imran Series, Ishtiaq Ahmed’s crime and adventure stories and detective novels by Ibn e Safi are probably the best examples.

"Storytelling has been the best medium to communicate since ages. And I strongly feel that the revival is only possible if we catch children’s attention first," says Sadia Sarmad, who is enthusiastically aiming to take her project of Urdu audio stories to a wider audience. "Once they have our attention they will listen and pick up, because listening skills are the first and foremost that develop in a child while growing up."

Blogger Tamania Jafri takes it a step further and shares resource material and interesting information about Urdu language on her blog. "My purpose is to share resources which can be helpful in learning Urdu with other parents. I write and share Urdu poems and stories and conduct a live Urdu storytelling session with my daughter every Saturday."

Urdu, an Indo-Aryan language of South Asia, is one of the 23 official languages in India and the national language of Pakistan. It is the first language of more than 60 million people around the world. For a generation to be able to speak and somewhat understand Urdu, but remain unaware of Ghalib, Meer, Iqbal, Faiz, Manto, Amrita Pritam, would be most unjust to the language, to say the least. If Urdu is to live on, the generations to come should get acquainted with the maestros who created this language. The generation at present can start this worthy cause.

Urdu hai jiss ka naam humin jaantay hain Daagh

Saaray jahan main dhoom hamari zuban ki hai