A revisit to the violent partition of the subcontinent and the accompanying nostalgia and trauma of divided lives

Dr Pippa Virdee is a familiar figure in both India and Pakistan not only because research on her doctoral dissertation and the book under review often brought her to both countries, but also because she is fond of the subcontinent. The book under review is yet another book on the academic literature on the partition of British India but it is a book with a difference -- this difference will become clear below.

The book has ten chapters and a preface which is important in its own right to understand the rest of this book. In it, she makes the point that the trauma of partition has still not been explored or resolved. In this work, therefore, she would ‘focus on the people’s history’ (p. xviii). It is just this which she has done in the most original chapters of this book and this deserves commendation. But before I come to those chapters let me mention her review of literature in the first chapter (partitioned lands, partitioned histories). I single it out for attention because it is one of the clearest statements about the state of historiography about the partition.

One learns about the major trends -- the history of decision-making from the British, Indian and Pakistani points of view -- and the defining characteristic of these trends is they are nationalistic and toe their particular, obviously biased, official narratives. Moreover, all of them refer to documents and the great actors in the drama of the partition in which the common people appear as statistics or parts of the arguments of the elites. She then mentions the subaltern school which opens up the possibility of exploring the lived experience of the ordinary people. Creative literature, which she mentions, is one tool for doing this and the other is oral history. These are the two research tools she relies upon in this book.

There are several other works which have used oral history to investigate aspects of the partition of Punjab. Perhaps the most notable of them is Ishtiaq Ahmed’s The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed (2012). Another one is Anam Zakaria’s The Footprints of Partition (2015) which traces out narratives about the life lived together by the different religious communities in British India. In India too there are several such histories one of which, Ravinder Kaur’s Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi (2007) comes to the mind.

Pippa Virdee’s book shares the methodology and some of the themes of such writings, but her emphasis is different from these studies. She clarifies that she intends to document ‘the experiences of partition and resettlement of women in Pakistani Punjab, especially in terms of how this is recorded in public and private spaces’ (p. 15). The emphasis on Pakistan, on women and especially on their resettlement is what makes this book different. This is a subject which has been written about in short stories and the partition narratives we have mentioned above, but it has not been dwelt upon by academic historians as much as it is in this study.

The next two chapters are of an introductory nature. The one on the Punjab is an introduction to the scene of the great tragedy and the second is about the decision-making which precipitated it. After clearing the decks so to speak, she comes to the violence itself (Chapter 4). This chapter is also of an introductory nature because it frames the story of the displacement of women which is the heart of the book. But here too Virdee refers to literary sources such as Khushwant Singh’s iconic novel Train to Pakistan (1956) as well as the interviews she herself has recorded. Moreover, this chapter quickly comes to the issue of the rehabilitation of the refugees.

It is chapter 5, however, which is both original and significant. It is on Malerkotla, a princely state in the Punjab ruled by a Muslim, Nawab Ahmad Ali Khan, which remained a haven of peace when the rest of the Punjab was bleeding. Malerkotla emphasised unity (ikatth) between different religious communities (Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus). Her interviewees told her, often with intense emotion, how they had suffered in the neighbouring states and how Malerkotla was where they found peace. The role of leadership in this atypical state is discussed and one agrees with the author that had partition been thought out by the leaders of the Indians and the British, such terrible suffering would not have befallen the ordinary people of South Asia.

The next chapter focuses on the way the refugees settled down in the lands they had to go to. The Muslims from the Indian Punjab chose to settle down in Lyallpur (Faisalabad now). The Hindus and Sikhs settled down in Ludhiana, the ‘Manchester of India’. There were reasons for both communities choosing these two cities. Both were suitable for business. Lyallpur specialised in textiles and Ludhiana, located along the Grand Trunk Road, was a centre of industry. Most histories stop at the settling down of refugees but Virdee goes into the nostalgia which the refugees experienced. They often named their businesses on their motherland: Ludhiana store; Lyallpur Sweets etc. Incidentally, nostalgia and sweet memories of shared life is also an important theme in Anam Zakaria’s book The Footprints of Partition which is one of the few books which sets out to record joys and not only sorrows.

The next two chapters (Chapters 8 and 9) are perhaps the most significant parts of Virdee’s book because these are one in which the author writes about abducted women and how they faced the trauma of their abduction and the shame of having been forced to live with their abductors. The excerpts from the interviews of these women or the fictional accounts about them are sobering and heart-wrenching. The fact that traumas of this magnitude have never been faced, hardly written about and not even recorded in significant ways is, indeed, staggering.

The last chapter mentions the few isolated monuments which do attempt to record the great tragedy but they are so few and far between that one despairs at the lack of interest in the project of forgiveness and reconciliation which has never taken place anywhere in South Asia about any major trauma: the partition of 1947; the wars about Kashmir and the violence unleashed there by militants, Indian security forces and radicalised young men; the military action by the Pakistan army on Bengalis from March till November and the vengeance of the Bengalis on unarmed Pakistanis and Biharis before the military action and after the fall of Dhaka in 1971; the brutal killings by the Tamil Tigers and the even more brutal extermination of the same by the Sri Lankan army in Sri Lanka -- all of them lie as unhealed traumas in the crypts of the beings of us South Asians.

One of the achievements of Pippa Virdee is that she has opened these old wounds. Let it be a beginning in the healing process which more such writings may facilitate. Pippa Virdee’s work is a landmark in the scholarship on the partition and will remain as an exemplar of the kind of writing we academics should aspire to if we are to write on emotive subjects which deeply touch us as humans.

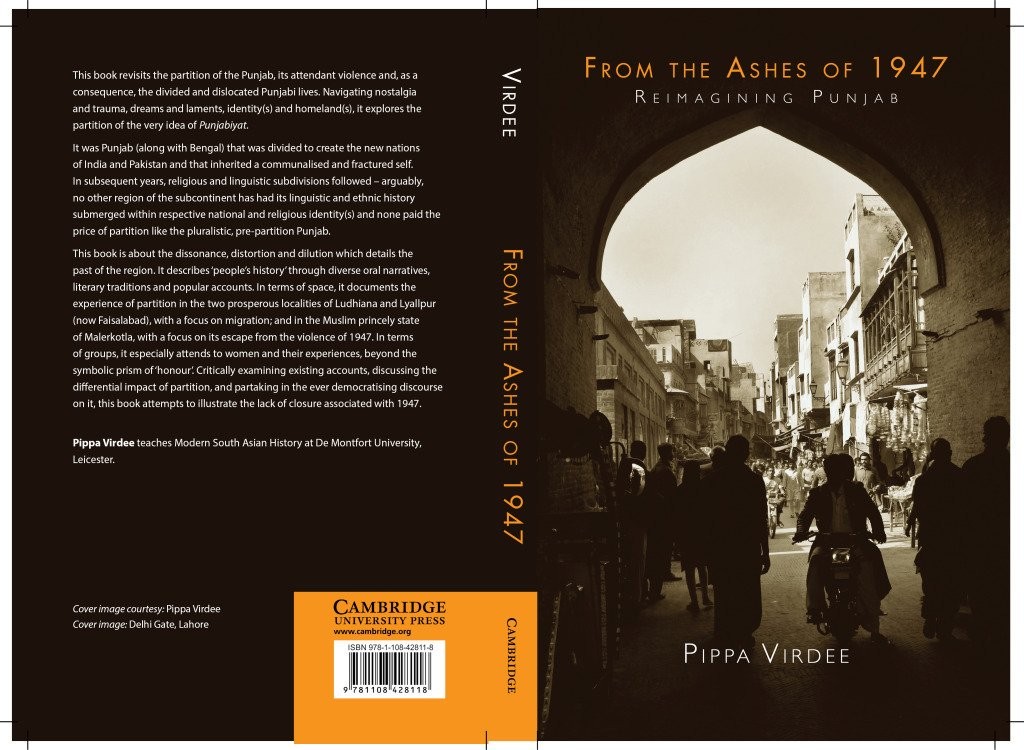

From the Ashes of 1947 Reimagining Punjab

Author: Pippa Virdee

Publisher: Cambridge University Press, 2018

Pages: 254

Price: Rs1,750