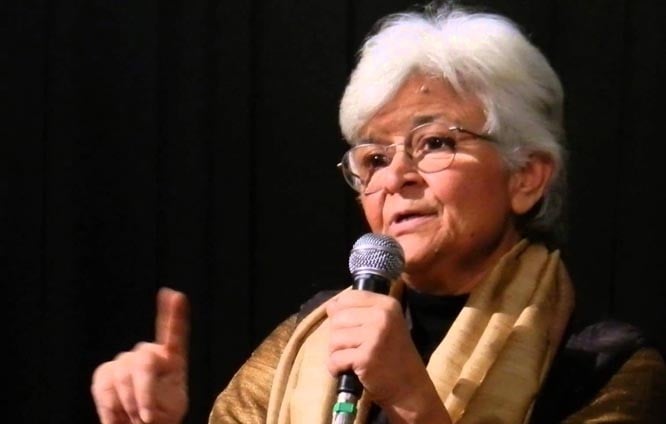

Kamla Bhasin, feminist, social scientist and activist, speaks about her struggle for equality in the world, especially South Asia and her deeply cherished bond with feminists from Pakistan

For more than two decades, Kamla Bhasin, along with other South Asian feminists under an organisation Sangat, has been organising a Feminist Capacity Building Course on Gender, Sustainable Livelihoods, Human Rights and Peace. The course which caters to more than 30 women from countries like Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Maldives and now Sierra Leone may be dubbed as a boot camp for learning about perils of patriarchy and intersectional feminism paving way for discussions over class, caste, nationalities, sexual orientation and others.

Before flying back to Delhi, Kamla spoke to The News on Sunday on a sunny afternoon in Kathmandu about bridging the ‘gap’ between old and new feminists and her memories of two great Pakistani feminists, Asma Jahangir and Madeeha Gauhar -- both passed away earlier this year.

Kamla doesn’t feel strongly about the generation gap.

"Whether we are old or new, we are very few."

"In the old ones, we had women from both APWA and WAF so I cannot generalise that old and young feminists have a gap. Today, in Pakistan we can see feminists from Awami Workers Party (AWP) and they do not necessarily have an issue with older feminists rather their struggle is directed towards eradication of poverty.

"However, if there are people who are solely focusing on the elimination of binaries in gender, one wonders if they would also speak on the issues of class or caste because those issues are equally important. If they halt at just pronouns, and if the only identity one speaks about is limited to sexual orientation, then they need to rethink their politics," she points out.

Kamla remarks that many groups exist among both old and young feminists and the latter are not all against the former, rather the older feminists are also changing.

"To think we have remained where we started from would not be correct because we change each day. I started working on development and class issues and then I became a feminist. I started working in the 1970s and around 1986 or 1987 I first encountered the term, gender. I didn’t know the word feminism because I went to a village school," she says in a matter of fact tone.

Speaking about her journey of evolving into a feminist, Kamla shares that she wrote a book ‘What is a Boy and What is a Girl’ in 1990s, in which she spoke about the two sexes, male and female: "But as I learnt more, I edited my books and wrote that there are three genders, and now I am writing about transgender identities instead of masculine and feminine. Today we are learning about digital violence so I don’t think we all are at the same place as we were years ago."

But Kamla doesn’t put the entire onus of the difference in perspectives between feminists on the younger lot; rather she feels that it is deeper than what appears in their views.

"Young people, whom we refer to as millennials, whether feminist or not, are caught up in consumerism due to the neoliberal structures surrounding them. I wouldn’t claim that we didn’t get stuck in its quicksand but the biggest difference is that we weren’t born and raised in it. For around 30 to 40 years, we did see alternate systems and structures. I have found for the last two decades that neo-liberalism is highly depoliticising in nature. Whether you like it or not, it gets you obsessed with consumerism and money, survival and competition and the façade of choices like the colour of lipstick," she explains.

She adds that the real choice lies with regard to the system.

"Earlier, we could live by Rs5,000 and could make ends meet by doing a choti moti naukri and make adequate time to do our feminism. However, now if a young woman wants to live in a city like Karachi, she can’t do so unless she is earning at least R40,000 to Rs50,000, and for that sort of a job one often needs to trade the soul. You’re a feminist but you’re working for a soft drink brand because one would work where they find a job. But feminism has nothing to do with these places and this word becomes a derogatory term and you don’t want to own yourself. Because in this pond, the feminist woman can be like a small fish and larger ones will devour her," she laments.

She empathises and stresses that she understands people are products of different circumstances, different political and cultural aspects.

"Those differences are there but it’s important that the old and the new get into a dialogue, and try to understand each other. Because whether we are old or new, we are very few. We are outnumbered so we can’t divide ourselves further. We all have our biases, I have mine: I find it very difficult to accept this whole beauty culture, and I feel this is what patriarchy emphasises on, or either the users of beauty products actually believe in it to be their choice. You can’t go to a mainstream newspaper of a channel if you don’t fit their standards of beauty. But then I see there are women who are all dressed up and are doing fantastic work too so one does question their own biases," she smiles.

But despite this, she believes in bringing biases to the table.

"I tell all to not be frightened of them. We don’t want to clone ourselves. As far as the causes are concerned, if we can’t be together on each and every one of them, we can at least find a common ground and work together and form alliances," she says.

She strongly feels that trainings which lead to women questioning their surroundings always go a long way and are in no way monotonous for her.

"I take these trainings like a challenge because every year they are new people. Has anyone ever told a painter that they are boring or did anyone ever tell Faiz that he had been writing poems for so many decades. I think if people are learning new concepts or even if they are challenging any aspect, our job is done because this journey isn’t a short one," she says.

Time with Asma and Madeeha

Taking a stroll down memory lane, Kamla speaks about her time spent with activist Asma Jahangir and theatre artist Madeeha Gauhar, whom she dubs as fierce feminists.

"I think I met Asma in 1983 or 1984. WAF was holding a jalsa, their first big jalsa, and they were unable to get permission from the police so they said they were organising a ‘mela’ to pretend they would put bangles stalls among others there. And inside we were holding the most political meetings against the then military dictator, Zia ul Haq.

Later on, when SAHR (South Asians for Human Rights) came about with likes of I.K. Gujral, Kuldeep Nayyar, Mubashir Hasan, Anis Haroon and others, Asma was looking for a place to set up the secretariat and my daughter Meeto stepped up, looking after their office in Delhi which brought the two closer to each other," she reminisces.

Speaking about a bus diplomacy service between India and Pakistan to promote peace activism, she said it was a coincidence that when the bus from India arrived in Lahore, the Pakistani women who were receiving the Indian women were both singing the song she wrote ‘Tor tor k bandhanon ko’.

"We had immense respect for her courageous mind and fearlessness. What I loved most about her was that she was a very political person but also a personal one. She would call me Kamla Kamli and even if she had half an hour she would come -- she made sure to ring and squeeze out time for me," she recalls.

Kamla met Madeeha while she was still working with FAO.

"Madeeha was running Ajoka and I used to arrange exchange visits during my time at FAO. In India, the street theatre movement or people’s theatre movement was quite strong. There was a man Safdar Hashmi, who was associated with CPM. He used to run a theatre group for trade unions and others. I asked if he wanted to visit Pakistan and then he went there and established contacts and started working with Madeeha. She often came to India and felt there wasn’t enough breathing space in Pakistan. She would visit India at least twice a year.

"All of her plays were highly political and her play ‘Bari’ on women in jail was a remarkable one. I saw the play in Lahore and invited her to perform it in India in 2004. She then did a play Ek Thee Nani, and we brought it to India and hosted it in Jaipur and we have an amazing bond via theatre. My younger sister hosted her and once again, the relationship was like that of a family. These are the women who disregarded borders completely and we are in awe of their struggles," she says.