In her current show at Canvas Gallery Karachi, Adeela Suleman reflects upon persistent conditions, but uses a language that is distinct in taste and distant in time

In Italo Calvino’s fantastic novel The Cloven Viscount, during the "battle against the Turks, Viscount Medardo of Terralba is bisected lengthwise by a cannonball". One part (the right side) is found and doctors manage to heal him. The left half is discovered by hermits, who "with balsams and unguents……. tended and saved him". The novel is about a conflict between two separated selves, right and left, good and bad of one individual, while both are competing for a village maiden, Pamela.

All of us are split beings. If you hit another person, you are injured too; when you kill someone, you also murder a part of yourself. In Adeela Suleman’s recent work, war-inflicted bodies missing a limb or lacking a head suggest an internal destruction too. In her sculptures, you see a man, one arm cut or without a head, in action moving a sword, holding a lance, balancing on one foot.

These immaculately fabricated figures, painted in light and bright shades indicate the presence of an age-old sentiment or sensation -- of romanticising and idolising violence. She feels that "the way people enjoy food, sex and sports, the same way they take pleasure in violence; because instinctively humans are very violent".

Violence in life and art is not the same. In real life it may involve different skills but in art you need a pair of scissors, an erasure, a saw, a chisel, tools of Photoshop, and video editing to execute it harmlessly. Through these visuals of violence, artists convey the state of a society.

For some years Adeela Suleman has been focusing on images which can be understood as traditional in terms of genre -- human figure and landscape. In the present exhibition (Sept 25-Oct 4, 2018, at Canvas Gallery, Karachi) one finds these two subjects. Human bodies are carved in wood and landscape is painted on metal sheets. However, in this simple division there exists a complex separation: of past and present, reality and imagination.

In her solo show one comes across two sets of armed personnel. First consists of a group of three men spreading their arms, and two identical soldiers aiming at each other -- all covered in modern day military outfit, yet without revealing their identity, or their nationality. The other comprises of crippled men who do not belong to our era but may be associated with this area (especially as depicted in miniature paintings).

The modern-day armed soldiers look ‘real’ while the figures from the past, with elaborate dresses and missing limbs and heads, convey a sense of fantasy, not much different from Calvino’s character. An allusion to illusions provided by history. One reads episodes and accounts of bravery of some of most revered personalities in our religious and cultural chronicles, but no one has the means to verify these descriptions. With the passage of time, these names have emerged as giants, obliterating truth in their shadow. The same process is happening in our current documentation of life. What is viewed in the name of fact on media is merely a fabrication, in which reality disappears. Hence the title of the exhibition ‘What May Lie Ahead’ is a double entendre.

So if the past is perceived as fantasy, the present is also projected as fib. In that sense both types of soldiers, from history and contemporary times, reside not outside but within ourselves, and are extensions of violence in our personalities and behaviours. At the same time, contemporary soldiers in Suleman’s work, due to their featurelessness appear as large-scale toys or decoration pieces, confirming that modern battles are a child’s play for world powers despite the death and destruction.

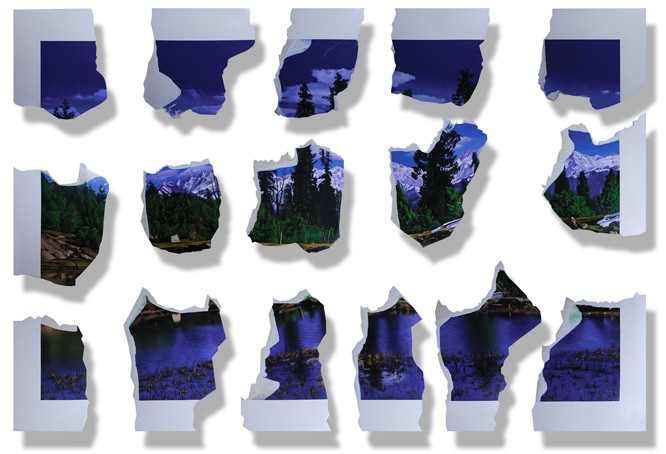

This death and destruction is represented in the way landscape is dealt with. In ‘Protecting His Land, 1&2’, standard postcard views of Northern Areas of Pakistan are rendered but behind piles of rough and unhewn stones. The perfect vision of beauty and calmness is shattered. The message is obvious: how terror has tarnished peace in a region that was away from political conflicts and constraints of globalisation.

More than these apparent readings, one can find other contents in Suleman’s work. In order to understand her concern, the choice of her mode of imagery is crucial. The artist has established her studio in a low-income neighbourhood of Karachi, where she employs artisans of various skills (wood carvers, ironsmiths, painters) who produce her pieces. There are several artists in our surroundings who have hired technical help that complies and constructs according to a high taste of art, as directed by the master artist. On the other hand, in Suleman’s case, people who are fabricating her work are not dealing with alien aesthetics. They are producing imagery popular and in circulation in their environment.

Not only because of the imagery and technique, but even in its content, Adeela Suleman’s art transcends the boundaries of classes. A dismembered swordsman is a reflection of a society that is fragmented. Military men in mirror-like positions, aiming at each other, can be seen a comment on a self-destructive situation. A shredded landscape is a clue to a broken societal system.

As a sensitive person and artist, Suleman reflects upon persistent conditions but uses a language that is distinct in taste and distant in time. Her wooden figures, besides invoking popular pictorial language, remind one of the tradition of sculpture in our region -- Gandhara art that flourished between 1st century BC to 7th century AD mainly comprised of stone figures of Buddha (hence the Urdu word for statue butt). Zahoorul Akhlaq used to describe them ‘two-dimensional’ due to the linear depiction of drapery’s folds. Creases in the costumes of Suleman’s soldiers are also portrayed in a descriptive manner. And so are the details of hands, fingers and nails.

The connection in these flat sculptures of army men and toy soldiers is a reflection on war -- a play of egos, interests and desires. Wars are generally waged in the name of patriotism, faith, freedom (and democracy). But behind these grand declarations, there may be some other reality.