His work emerging out of Vasl residency proves that the city for Haider Ali Naqvi is just not a canvas to paint but a point to ponder

You are disoriented. Is it an art space or a violent zone with demolished buildings and debris scattered around? Soon, you come to know it is the display area of an artist’s work. The city is Karachi, that is apparently calm these days but remains on the verge of a breakdown, and you are in a building that is being repaired but is temporarily used for ‘Conurbations’ -- art pieces produced after a three-month Vasl Residency.

Haider Ali Naqvi, a 2015 graduate of Fine Art from the National College of Arts, was selected for the Residency, and spent the months starting from May to August 2018 at the Vasl studio. During those months, he "developed a body of work which reflects on the changing landscape of his city and surroundings". The way it was arranged (August 27-31 at the venue) amid rubble on the top floor of Karachi Arts Council reminded of a far-off location -- Hans Haacke’s ‘Germania’ at Venice Biennale 1993. Haacke, representing Germany, destroyed his country’s national pavilion that in 1938 was rebuilt by Ernst Haiger "to manifest the principles of Nazi aesthetics".

A young person who had spent most of his years in Karachi, Naqvi is part of the city as much as the city becomes a fragment of him. We all are segments of one or another town, both metaphorically and physically. After death, we are buried in its soil but in life too our residences are minuscule manifestations of the city.

For most artists, city inspires views of streets, alleys, seaside, rendering of buildings or boats. Beyond these picturesque pleasures, city is a difficult entity.

Today’s Karachi is difficult in many ways. It is a place where groups of population are struggling for their rights, influence, power and safety. It is also a place that fell from the glorious and glamorous grace of 1960s and ’70s to the depressing 1980s and ’90s. Ethnic, and sectarian conflicts characterise the port city. However, it still is trying to find peace and prosperity, absorbing a mixture of inhabitants from within the country and without.

A person who lives in ‘jungle of cities’ (coined by Bertolt Brecht) has to deal with his immediate surroundings; such as transport, crowd, cramped houses in narrow neighbourhoods. Negotiating that situation, a sensitive artist observes how a space constructed by humans eventually affects them, transforms them, modifies their pattern of being as well as their system of thought.

In publications and presentations on urbanity, one is struck by charts of growing population. This may impress a technocrat or a reporter but for many these statistics are merely abstract amounts; accumulation of zeros. On the other hand, the experience of being in a city swarming with people is more common and convincing. Haider Ali Naqvi has composed his drawings of the metropolis in a way that large papers with sensitively depicted views of buildings are cramped inside relatively small frames: perhaps recalling the pressing population. His images of areas close to a saint’s grave denote how life revolves around death. Thus children’s rides, fortune teller’s set-ups, vendors’ stalls are all next to Abdullah Shah Ghazi’s tomb. His large work depicting mausoleum of Quaid-e-Azam, drawn next to houses and high rises in the locality, is split into nine tightened frames.

Apart from his impressive skill in capturing details of a big monument and adjoining buildings, the artist has focused on the condition of a brimming city. So, his drawings are also confined, compressed and contorted within frames. This is not a random choice because the artist extrapolates with the ‘usual’ proportions of an artwork. In two of his canvases, executed on surfaces resembling an open Chinese hand fan, he has painted housing societies (BahriaTown and Creek?) stretching normal views in order to convey the extent of expanding population.

The city for Naqvi is just not a canvas to paint but a point to ponder -- about distinction, disjuncture, disparities and disappointments. Pictures of new properties, in a way, (perhaps not intended by the artist) comment upon the divide between the haves and have-nots.

During his residency period, he invited people in the surroundings of Abdullah Shah Ghazi’s Mazaar to make drawings of the building. All these attempts are included in his exhibition. Naqvi also photographed certain sections and characters around that vicinity as a chronology of life and activities, flourishing even if on a subterranean level. These photos and drawings indicate that the world is seen in a different light and language by different groups.

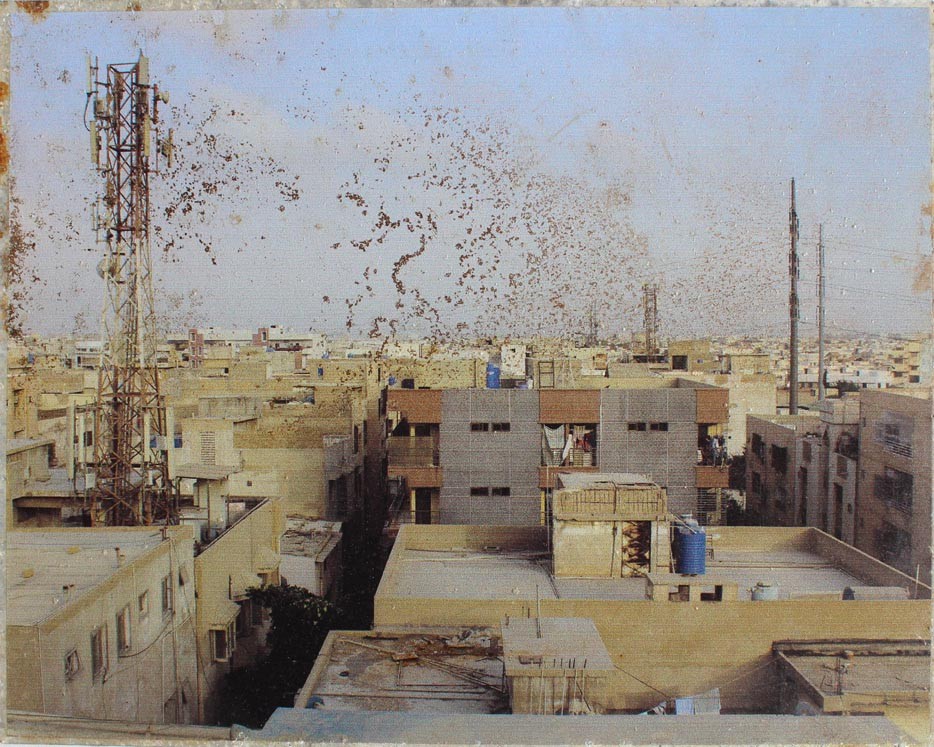

Naqvi’s act of printing map of each town of metropolis on iron plates, leaving them, collecting them after variations in eroding and his pictures and changes in pictorial resolution due to the passage of time, address the diversity of responses to one’s background.

Two important aspects of Naqvi’s work are formal (effect of age and greyness of imagery). "I am intrigued by rupture caused by human development and the inevitable forces of nature" he says. The physical deterioration can be read as a metaphor of breaking down of social structures of the city. This is a place that has been stripped of beauty. Most of his works -- from fabulously rendered pencil drawings of several parts of the city to monochromatic paintings of its multiple localities -- are a means to reinforce the essence of a concrete world which is not suitable to sustain colours, or other decorative features.

Although Karachi, known as the city of lights, is still vivid, vibrant and thriving, yet some parts communicate a semblance of bare and unbearable existence. Cement structures, barren lanes and heavily populated quarters represented in Naqvi’s work remind one of French poet and critic Mallarme who said: "Everything in the world exists in order to end up as a book". Except in Naqvi’s case it exists to end up as art.