What is more crucial for human consciousness? Words that attempt to make things more precise, or music that keeps them broader and more generalised

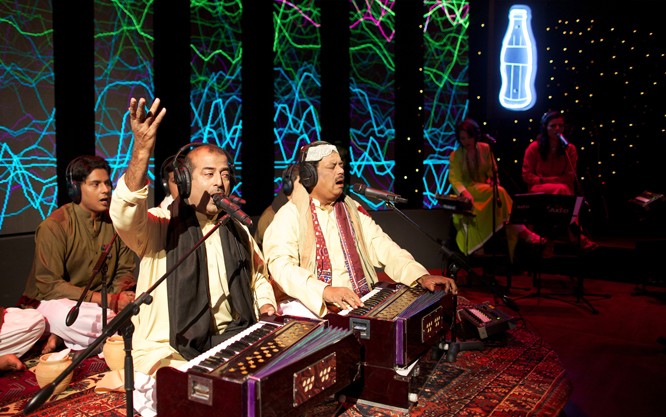

In this season of Coke Studio, poems of two important poets Iqbal and Faiz have been sung by Fareed Ayaz, Abu Muhammad and a host of other vocalists. There were objections in the case of Faiz that certain of the more volatile lines or rebellious verses were not included in the rendition; in other words these were edited out on purpose. In the case of the qawwals’ rendition of Shikwa and Jawab-e Shikwa, a few verses were added that actually did not belong to Iqbal.

As is the general trend, the verses had been sung by other very famous vocalists in compositions made decades ago, and these were a kind of a refurbished version with visual opulence that is the forte of Coke Studio. Probably the mission statement of Coke Studio is to make an effort at refurbishment of melodies that have been proved popular by time, and in that they have probably been successful in attracting the attention of the younger generation who are either unaware of their past and its cultural landmarks or are unresponsive to them unless repackaged in contemporary sonic intonations.

Iqbal Bano’s ‘Hum Dekhain Ge’ in the mid-1980s, a composition by Israr Ahmed, a connoisseur of music, an academic and a part-time composer who was very well-known in the music circles of the city, had such an impact due to the volatility of the verses rendered by her in times that marked by the extreme oppression of Zia ul Haq. It was probably tolerated as Mohammed Khan Junejo’s government had taken over as the junior partners of the military regime and was giving the impression that it wanted resumption of democratic activities, the first requirement of which was tolerance and acceptance of the value of more voices than one in society.

Probably Shikwa and Jawab-e Shikwa were sung for the first time by Mubarak Ali/Fateh Ali in the form of qawwali as, with the creation of Pakistan, the noose of censorship was narrowing all the time. The qawwals and the kalam of Iqbal were considered to be the first line of defence against those who wanted cultural expression to be based on its theological understanding and so tightly regimented through censorship from the top.

But the qawwals or qawwali by its very form is not supposed to stick to either the lyrics of a single poet, a particular ghazal or nazm and also be faithful to one single melodic pattern. The virtue of qawwali is actually "girah lagana" which means that the qawwals are free to decide at that very moment, if there are other verses that can be integrated to the musical expression of qawwali to further it through an evening’s performance. Similarly, they have the freedom to move from one raag to the other which again the form provides, the only value being the music appropriateness of it. In other words the lyrics are subordinate to the musical structure of the qawwali.

The general perception or a layperson’s understanding about music -- that it is poetry sung or lyrics rendered in music -- is half truth and can totally lead you into a blind alley. Along with it is the common corollary that the purpose of music is to enhance or augment poetry or the words and to communicate in a more heightened form whatever is embedded in the words.

It also implies that music as a genre or an art form is subservient to the word for it is meant only to take a step forward what is only there primarily in words. It can also imply that since, in a society, the general or the major potion of the population is illiterate it is through music or singing that much of poetry is communicated to the people at large.

As we move towards the popular forms of music, the understanding of music is or the retention in memory is actually of the verses or the lines that form the mukhra of the bandish. People generally recall a certain song by its mukhra and in the company of friends usually make it into a collective recall. But as one moves away from popular forms, the lyrics the words just phase out and become secondary and are pushed to the sides, and at times even become totally irrelevant because other aspects or parts that are purely musical take over.

Whether music operates through words or through surs or notes has been subjected to much research and scientific investigation, but no conclusive findings have been reached. But, definitely, it is universalising an experience or an impression much more than the concreteness that words are supposed to strive for. It addresses the visceral than the conceptual.

Probably the process is different, one may be of making things more precise, the other to keep them in a broader generalised form. It is a matter of debate as to what is more crucial for human consciousness: one or the other or probably both. But it is for sure that one is not a substitute for another or a mere replication. Probably both touch human experience as encounters of another kind.

It is no wonder that the musicians and vocalists use lyrics very casually and play around with them more as sound patterns than words with a designative connotation. Music has none, and here the word and note are at cross purposes.