As the new government in Pakistan announces the liberalisation of state-run media, a look at the history of PTV’s news bias and censorship

A new government has assumed the reins of power, and keeping alive the tradition in this country, the state-run media, especially PTV are in the eye of the storm. In his first address to the nation, Prime Minister Imran Khan perhaps fortuitously forgot to mention matters pertaining to the media, especially the lingering questions of press freedom. The lapse was all the more conspicuous as the new leader and his political party owe their rise to the media in large measure.

Keeping the invisible machinations aside, for more than 20 years, the media focused on a political wannabe whose sole claim to political space was a single National Assembly seat till 2013; and that lone seat was won in 2002 general elections held under the tutelage of an army dictator. By a conservative estimate, the electronic media aired more than 300 solo interviews of Imran Khan during 2001-2013 while political stalwarts like Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif, Asif Zardari, Fazal Ur Rehman and Asfandyar Wali languished in orchestrated oblivion.

One nebulous exception to the rule was erstwhile chief of MQM, Altaf Hussain, whose meandering telephonic theatrics from London jarred upon public ears even at odd hours of the night. But then Hussain and his party were playing a different ball game altogether.

The omission of press and media from the inaugural address of the newly elected prime minister sent ominous vibes regarding the new government’s sensitivity towards the role of free press in a democratic dispensation. It was disconcerting in the context of the undeclared but widely known restrictions upon the media during the months leading to the election day.

Perhaps, in an effort to alleviate the anguish among media circles, the newly appointed Federal Minister for Information Ch. Fawad Hussain tweeted on August 21 that political censorship had been lifted for state-run PTV, Radio and official news agency APP. Importantly, the worthy minister chose to release such an important information through a microblogging social media outlet rather than more formal procedures like an official directive or notification.

After a week in office, the information minister, while talking to media persons outside the Senate building, divulged that the government had decided to abolish PEMRA and Press Council and establish a single regulatory body which would cover print media, electronic media and social media. The fine print for the said proposition has yet to see the light of the day.

Thus, it is pertinent to look into the dynamics of press freedom in general and more specifically the editorial matrix of state-run media.

Pakistan inherited press and radio from the colonial rulers in 1947. While radio was a veritable mouthpiece of the government, the print media had a checkered history strung with frequent bouts of acrimony and hostility with the government. The founder of the nation was undoubtedly a great proponent of free press. His 1919 speech on the floor of the Imperial Legislative Council, denouncing Rowlett Act still reverberates through the annals of press history in this part of the world. He said, "If you allow me to say it, you also, by default, allow me to publish it". Jinnah fiercely defended Bal Gangadhar Tilak in 1916 and later B.G. Horniman of the Bombay Chronicle.

He founded Dawn (Delhi) with the standing instruction for the editorial staff, "Write in the light of your conscience. It is not my job to tell you what to write". It is ironic that Quaid-e-Azam himself was the first purported victim of censorship in the nation that he founded. Zamir Niazi, that legendary chronicler of press history in Pakistan, has laid threadbare the story of how pygmy bureaucrats tried to suppress the solemn pledge of equal citizenship that the great leader made to the nation.

Immediately after the demise of Jinnah, the Civil & Military Gazette fell victim to intolerance of the government and myopia of the media fraternity who colluded in the ignominious act of muzzling a newspaper by publishing a joint editorial demanding the suspension of the publication.

The first two decades of radio in Pakistan were heavily influenced by the professional competence and political fickleness of Z.A. Bukhari. Bukhari had learnt the ropes of propaganda under the British government and hardly espoused the integral link between free press and democracy. A glaring instance of his acquiescence to the powers-that-be was the censorship of Fatima Jinnah’s radio speech on the occasion of the death anniversary of Jinnah in 1951.

Understandably, the new state had to instil a sense of confidence and hope among the citizens. However, a positive image of the nation and its prospects certainly do not mean a blackout of facts. The state-run media in Pakistan adopted the policy of erasing, manipulating and distorting history according to the dictates of the government. Inevitably, it led to a corrosion of credibility.

The oft-repeated ploy of singing panegyrics for each government and denouncing it the moment it departed not only left the public confused, it also contributed to the mutilation of political consciousness among the masses. The arrival of a military dictatorship in 1958 nailed the matter once and for all.

It is intriguing that a nation that won its independence through ballot box was, within 10 years, unable to grasp the enormity of the tragedy that befell its way through abrogation of the constitution and imposition of military rule. Undeniably, the conformist and pliant character of the media through the first decade of independent Pakistan played an important role in such distortion of public mind. A magical mantra was devised for the media: the politicians were corrupt, incompetent and inefficient while non-political, transparent and efficient patriotic forces were the only guarantee for progress and security of the country at the expense of the din of democracy.

While the gimmick worked, it had some inherent flaws. It created a facade of false hopes that ultimately led to the downfall of successive regimes. The 1965 War with India was a stand-out performance on the part of media but it also paved the path of disillusionment in the wake of the Tashkent Agreement.

Through the fateful year of 1971, the nation knew next to nothing about the situation in what was then East Pakistan. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came to power amid grand promises of abolishing the Press & Publications Ordinance and dissolving the National Press Trust. However, the release of a short film about the last rites of East Pakistan brought such pressure upon the Bhutto government that it forgot about freedom of press. In fact, the five odd years of PPP’s first stint in power was full of atrocities against the free press.

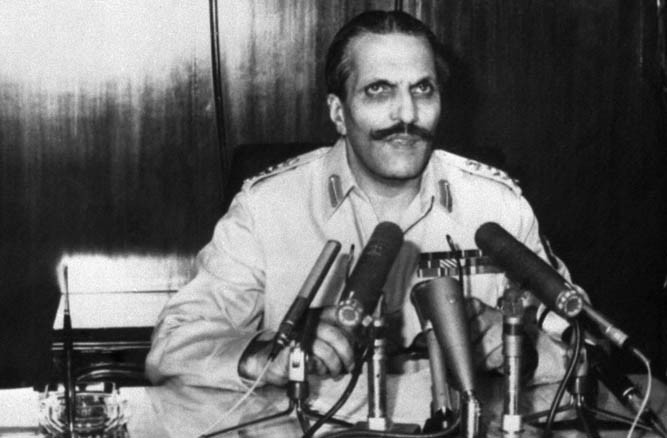

Television arrived in Pakistan in 1964 and emerged as a powerful medium under the stewardship of people like Aslam Azhar. However, the success of Pakistan television owed more to its entertainment segment rather than news coverage. While drama, sports and cultural content of Pakistan television was appreciated deservedly, its news section was a visual advertisement of the government in power ad nauseam. Pakistan television developed a bi-polar character. Entertainment enjoyed relative freedom but news and analysis programmes were the undeclared fiefdom of the government. A list of no-go areas was created and, as expected, the political class didn’t make its way to the sacred inventory except the party in power. The news segment clearly indicated who called the shots in the country.

In 1985, Prime Minister Junejo’s speech on the floor of the house was censored because he had declared democracy and martial law mutually incompatible. A brief respite in this ignoble tradition appeared under Information Minister Javed Jabbar towards the end of 1988 but PM Benazir Bhutto soon chose to replace him under pressure from her own cronies. The story of Pakistan television is a tale of unsavoury trivia.

Military dictator Pervez Musharraf is often credited with allowing the mushroom growth of private electronic media. It is debatable that this measure was taken in the interest of free press or to counter certain international developments. The media policy issued on November 3, 2007 belies the claim that Musharraf had genuine commitment towards a free press.

Times have changed. Pakistan television and other state-run media have become virtually dysfunctional in the presence of scores of private channels and emerging social media. Pakistan television still enjoys some huge advantages. It has terrestrial access through boosters, making it available for 97 per cent of the population. It also has monopoly over the compulsory television license fee accrued by the government along with electricity bills. PTV has more infrastructure and personnel strength than other private channels. However, these benefits fail to translate into concrete advantage because the staff is highly incompetent and in perennial fear of government’s wrath.

The crisis of state-run media in Pakistan is embedded in the dual crisis of legitimacy, transparency and authenticity of governance. Democracy is fragile and political forces, for now, appear content with the veneer of power. It results in lack of professional authority in the work force and the trust of viewers and listeners.

The new government in Pakistan has announced the liberalisation of state-run media and, on the face of it, that sounds good. Realistically speaking, government is in no position to risk the loss of the sole channel at its disposal in the face of a vigilant and vociferous private press.

Only last week, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) has released a fact-sheet concerning restrictions faced by private television channels, newspapers and journalists. The incidents included in the well-documented report hardly offer a ray of hope for freedom of press in this country. While it is too early to judge the performance of the current government, the context of the debate and developments in recent past do not auger well for the press; print or electronic, state-run or private.