Spectacularly present on London’s Serpentine Lake South London, the sculpture ‘The London Mastaba’ is part of an exhibition of two creative minds Christo and his wife Jeanne-Claude, along with a display of their other works at the Serpentine Galleries

Standing on a bridge in Hyde Park and looking at the latest work of Christo, one is forced to recall the infinite story of a ruler who had ordered the beheading of the storyteller as soon as his tale ended. The story went something like this: there is a mound of grain, one bird comes, picks a particle and flies away, another bird comes, picks another piece and flies away too, yet another bird comes and so on.

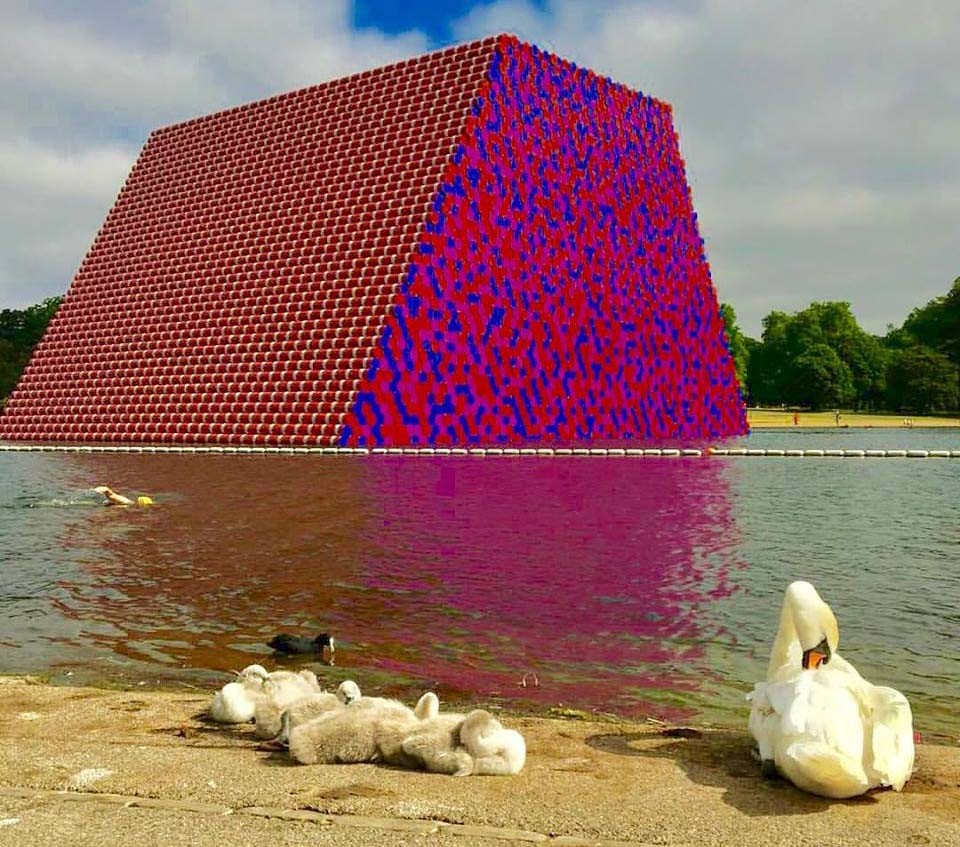

Christo’s ‘The London Mastaba’, a 20-metre-high sculpture made from 7,506 horizontally stacked barrels, floats on London’s Serpentine Lake (from June 18-Sept 23, 2018). One knows the exact number of drums used to construct this monumental work, yet that amount is as abstract as the total count of grains in the fable. The barrels are innumerable, like the blocks of stones in Khufu’s Pyramid (about 2,300,000), which continues to astonish a visitor even after 5000 years. This earliest pyramid (c. 2610 B.C) of King Dzoser, supposedly designed by his minister Imhotep, evolved from a ‘mastaba’ (meaning bench in Arabic). "The term ‘mastaba’ originated around 6,000 years ago in the ancient region of Mesopotamia".

Now mastaba has moved from Middle Eastern soils to a lake in London which, instead of regular building material, is composed of disused drums. Painted in different shades of red, blue and mauve, ‘The London Mastaba’ seems to sail on water; however the artist’s choice for barrels has an intriguing connotation. These containers used for storing and transporting a liquid -- oil -- are placed on another liquid -- water. Somehow, the knowledge of their hollowness accentuates the feeling of them being suspended on water, like an inflated tube or a lifesaving jacket.

Christo, with wife Jeanne-Claude who died in 2009, collaborated on "countless public projects, including ‘Wrapped Coast’ (Sydney, 1968-69); ‘The Pont Neuf Wrapped’ (Paris, 1975-85); ‘Wrapped Reichstag’ (Berlin, 1971-95); ‘The Gates’ Central Park, New York City, 1979-2005, and most recently ‘The Floating Piers’ (Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16) and a number of proposals, about covering museums and public buildings.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s works mostly convey the concept of concealing. Yet one is able to recognise the hidden object and the underneath structure. The works can be about realising multiple interpretations and levels of reality. These turn buildings made of stone, steel, mortar, brick and timber into humans, since only human beings clad themselves in clothes; or they may be read as a comment upon marketing because a product is often sold and presented in a package.

Whatever way one approaches, the duo’s art was an attempt to come out of the gallery and showcase art in public sphere. And yet it was not an exercise in diluting their aesthetics for the general population; they just operated in the public domain. Thus, it may be puzzling for residents of a certain locality accustomed to seeing a structure in its ‘normal’ state for years, and one day find it wrapped in fabric.

For Christo and Jeanne-Claude, art could be a means to transform perceptions about the world around us. But that world is not merely the world of art, it encompasses much larger dimensions: politics, capitalism, environment, and the exclusivity of art. In Christo’s opinion: "mastaba is an extraordinary form -- for me, more beautiful than the pyramid… It is above all, the result of a balance of forces."

Spectacularly present on the sheet of water in South London, ‘The London Mastaba’ can be enjoyed fully if one steps inside the Serpentine Galleries, not far from the sculpture, and knows that the project was initially conceived for Abu Dhabi, UAE in 1977. The world’s largest sculpture ("made from 410,000 stacked barrels and standing 150 metres tall") was proposed to be put in the middle of a desert. But as fate would have it, it is placed in London, a city in which many artefacts and artworks from Mesopotamian and Egyptian Civilisations are on display in the British Museum.

More than the magnificence of the project, it also testifies an important aspect of art and regionalism -- of an artist’s decision to investigate an art practice, removed in time, place and tradition, and appropriate it for another purpose. The use of word mastaba in the title of the artwork signifies the link with the ancient Middle East, yet the work of Christo is an example of contemporary art that survives on diverse sources. So The London Mastaba sculpture can be perceived as a contemporary Ziggurat or Pyramid, displaced from the Mediterranean land and housed in the middle of British metropolitan.

The exhibition ‘Barrels and The Mastaba 1958-2018’, at the Serpentine Galleries (June19-Septmeber 9, 2018) reveals two creative minds that investigated form, structure and space. Rooms are filled with works that contain multiple possibilities of working with barrels, starting from an exhibition in 1961, when "for Stacked Oil Barrels the artists used machinery to amass oil drums into large scale structures". Drawings, collages, small scale models, prints, photographs (made by both artists) all lead to the huge sculpture that has materialised outside the gallery space.

Visiting the Galleries was like entering the mind of the artist, and recognising how an idea multiplies and becomes a tangible entity. A work that is registered by everyone walking in that area in Hyde Park; its presence cannot be ignored, much like the impact of Egyptian pyramids which control and captivate by their scale and relation to adjoining space.

However, the magnanimous sculpture does not overpower you due to its scale, it becomes part of your psyche on the basis of its detail ("God is in the detail", said Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the German-born architect). Variations on drums’ composition -- of colour and form -- keep on unfolding room after room, with some three-dimensional pieces on display. In the process, the exhibition becomes a testimony of how an idea becomes a work of art.