Dear All,

Thirty years ago, on the afternoon of August 17, I was sitting at home in Karachi when the bulb on a wall light shattered suddenly. It was slightly alarming, but I was more concerned about the fact that local television transmission appeared to have been suspended. A written notice appeared on PTV, and stayed on the screen for hours, I don’t remember the exact words, but it was something to the effect that normal transmission would be resumed shortly.

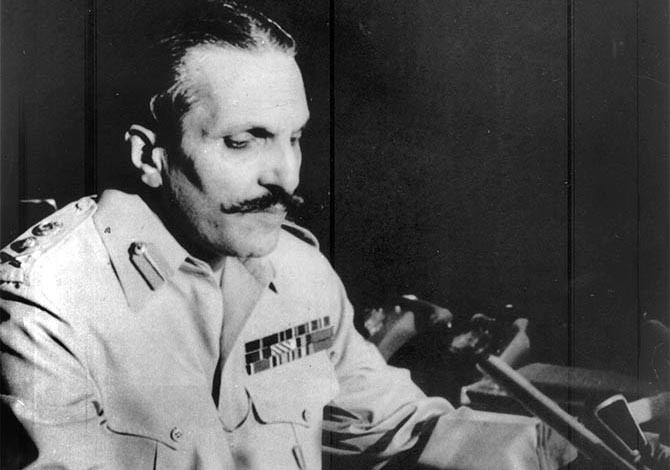

But then journalist networks began to buzz with reports that General Ziaul Haq’s plane had crashed somewhere near Multan. As information trickled in, it was learnt that the ISI Chief General Akhtar Abdur Rehman and the US Ambassador Arnold Raphael had also been on the plane. Finally, some eight hours after the crash happened, the then Senate Chairman Ghulam Ishaq Khan appeared on TV screens to address the nation and inform us that General Zia had died in a plane crash.

He was fairly emotional as he announced that "Humaray maboob sadr ka tayara hawa may putt gaya" (our beloved president’s plane exploded in midair).

The words and the way he said them, with a heavy Pakhtoon accent, made them unforgettable. It was also an unforgettable moment because for 11 long years General Ziaul Haq had ruled Pakistan with an iron fist and had changed the face and psyche of the country almost completely.

Zia had deposed Pakistan’s elected Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in July 1977 in the midst of political negotiations following accusations that the elections had been rigged. The general appeared on our television screens in full uniform, announced that the military had taken over, that he would hold elections in 90 days and, famously, that he "had no political ambitions".

Elections were not held in 90 days, in fact they were not held for another eight years. As for having "no political ambitions" that was belied by the fact that Zia refused to relinquish power and even dismissed his own chosen Prime Minister Muhammad Khan Junejo when the latter began to suggest that Presidency should be run more frugally, that the armed forces should be accountable for incidents like the Ojhri Camp blast and that foreign policy, particularly Afghan policy, should be decided by politicians, not the establishment.

Once he took over, General Ziaul Haq used the religion card to full effect. Even the traditional lore that Muhammad bin Qasim brought Islam to the subcontinent was overshadowed by Zia’s own policies of bringing ‘true Islam’ to Pakistan. He used the forces of religious obscurantism to counter rational discourse and political dissent, and conflated Pakistani identity with being a Sunni Muslim.

He crushed any political activity and browbeat the media. He also brutalised the psyche of the nation by turning public executions and lashings into a sort of spectator sport. Journalists were whipped in public. Women were humiliated and hemmed in by oppressive laws. Student unions were banned but the religious parties’ student wings were allowed to terrorise university campuses.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was convenient for the martial law regime because Zia became an important American ally, and the Reagan and Zia administrations trained and exported Islamic militants to defeat the Soviets. The dollars poured into Pakistan, and a lot of people became very, very rich during this very dark period of the country’s political history.

What Zia really did was polarise the nation in much the same way that Chile’s Pinochet did in the 1970s and 1980s. He consolidated the right wing and normalised intolerance and hate mongering.

It was a bleak and difficult landscape into which exploded the news of the general’s death on that August day. Many mourned the death but to others it felt as if dawn had finally come after an excessively long and dark night. We felt it was some sort of deliverance but were unsure how to behave in a Pakistan without the General…

And now three decades later, we realise that, alas, we can probably never have a Pakistan without the general. We are still entangled in oppressive religious laws and mired in intolerance, hate mongering and violent practices.

In that sense Zia lives on: zinda hai Zia, zinda hai….

Best wishes