The August 12, 1948 massacre in Babara is a reminder that nonviolent Pashtun movement has not lost its steam

During the nascent stage of Pakistan, on August 12 1948, the first step was taken in a plot to remove the voice of dissent and a populist movement in the then North-West Frontier Province of the country. On the ill-fated day, a total of 600 unarmed Khudai Khidmatgaars were killed (unofficial accounts of the massacre puts the number of dead higher than the official count) in cold blood by law enforcement agencies.

The then chief minister of the province, Abdul Qayyum Khan, on the pretext to uphold the provincial government ordinance promulgated in June 1948 by the governor, authorised the government to detain anyone indefinitely and confiscate properties without disclosing any reason to the detainee. The ill-thought-out action indicated the hopelessness of the state and was followed by a ferocious campaign of repression that was mounted on the province.

On the morning of August 12, 1948 scores of Khudai Khidmatgaars started to assemble in Utmanzai, hometown of the movement and Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Bacha Khan. Despite the imposition of Section 144, the Khudai Khidmatgaars were adamant in carrying out their peaceful rally against the atrocities of the provincial government and the arrest of the movement’s leadership from Utmanzai to Babara, Charsadda.

The newly-promulgated ordinance allowed the state to use force with impunity to squash opposing voices and detain anyone the state deemed a potential threat to its existence. All those detained were not even allowed to challenge their arrests in the courts. The motives were political as the governor of the NWFP stated that the ordinance was promulgated on the special orders of Governor General of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

On the afternoon of the August 12, all hell was let loose on the Khudai Khidmatgaars when they started off with their march towards Babara. Men, women, old and young -- none was spared. Without retaliating, the women and old among the crowds pleaded the forces to stop the indiscriminate firing but their pleas were not heard. With all hospitals told not to take in any injured from the rally, many died a slow death from their wounds.

The atrocities committed on that day were proudly flaunted by the then chief minister, Abdul Qayyum Khan, when he gave a statement in the provincial assembly in September 1948, "I had imposed section 144 at Babara. When the people did not disperse, firing was opened on them. They were lucky that the police had finished ammunition; otherwise not a single soul would have been left alive and if they were killed, the government would not have cared about them."

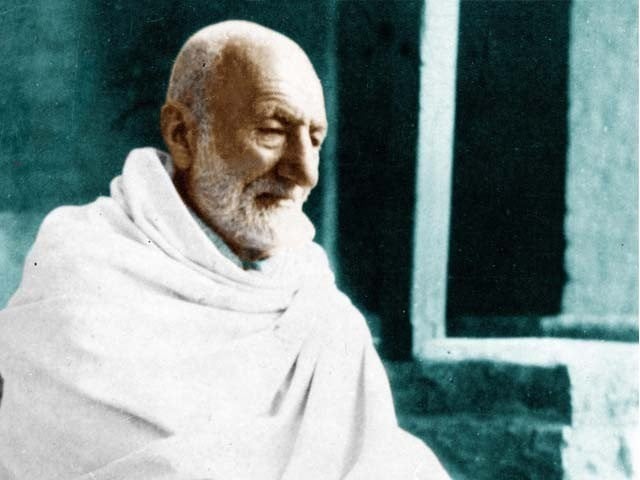

It was here in Utmanzai, Peshawar, and elsewhere that the Khudai Khidmatgaars suffered some of the most severe repressions of the entire Subcontinent Independence movement. This was at least in part because, as Bacha Khan later said, the British thought a nonviolent Pashtun was more dangerous than a violent Pashtun. As a result the British Raj was always busy plotting to provoke them to retaliate. It was during these times that the entire province was hidden from the sight of the outside world and the military and law enforcement agencies were given a free hand to suppress the nonviolent movement with an iron fist. The Khudai Khidmatgaars were warriors in every sense of the word. They were prepared to die in the struggle against imperialism, and many did. They were prepared to die for their cause but not to kill for it.

The Babara incident was called worse than the massacre committed by the British in Jallianwala Bagh in 1919 by Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy while addressing a public rally in Dacca in July 1950. Bacha Khan said on the issue during the budget session of Assembly on March 20, 1954, "Six years ago, I announced on the floor of this House that Pakistan is our country and its solidarity and protection is our duty and that any programme that will be submitted by any party for its progress and its reconstruction shall have my fullest cooperation. I repeat those words of mine even today. But still there are some persons who suspect my loyalty. I therefore think that it would be advisable to set up a tribunal to inquire not only into the question of loyalty or treason but also into the general massacre, arson and loot and the dishonoring of women and children and old men at Charsadda and the oppressive treatment meted out to us in jail."

The subjugation of the Khudai Khidmatgaars was being accomplished by coercion and terror, pure and simple. Unfortunately, these methods of suppression used by the British Raj was transferred to Pakistan, which became unnecessarily aggressive to squash a dissenting voice and overly repressive in the name of national security. British officials and journalists called Abdul Ghaffar Khan "a fanatic, bitterly anti-British Pathan", associating him with violent uprisings that occurred elsewhere in the NWFP to impugn the non-violence of his movement.

Similarly, the Babara Massacre was systematically erased from the hearts and minds of the people of Pakistan when two days after the incident the country celebrated its first independence anniversary with speeches of victory. But the day and events that unfolded on that day have been passed down through generations in the form of folklore.

The Khudai Khidmatgaars movement that was thought to have been squashed has resurfaced in the Pushtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM), indicating that Pashtuns are fed up of extremism and terrorism. The PTM has recently seen some of their demands met but still, their struggle continues.

Once again, Pushtuns are adhering to nonviolent means and methods to protest their grievances, a notion that holds symbolic importance for the people of this region. For them every popular movement is born in tragedy.