The cause of democracy demands that all questions related to the alleged manipulation of the elections are resolved, else people will lose hope, that a fair election can ever be held

Much before the country went to the polls, fears had been voiced that Pakistan’s democracy might lose Election 2018. It is too early to claim that this prediction has come true but the challenges to whatever democracy we have had have surely increased.

There is near total consensus that the country needs above all a strong government, strong not in rhetoric or in painting black as white, but strong in planning a way out of the multiple crises confronting the state and strong enough to take the people into confidence. The coalition government that Pakistan will soon have is unlikely to possess the total strength of the component parties; it could be weighed down by their combined weaknesses. Unless it makes an extraordinary effort, its inexperienced team may not secure the means needed to push the country forward, and the democratic system might be blamed for everything that goes wrong.

Most parties that want to capture power offer all kinds of assurances of benefit to whoever can deliver a bagful of votes to them. The rewards promised are not limited to a share in authority; they often include understanding about adopting courses in the interests of the groups whose support is solicited.

Justified under the excuse that everything is fair in love and war, such deals are not always mentioned prior to a party’s coming to power. In the case of Election 2018, Imran Khan deemed it prudent to repeatedly announce that he was determined to win the election and the means that had to be used didn’t matter. His party will be under an obligation to honour the promises made to defectors from other parties and groups such as the PML-Q.

There may be other parties that facilitated the PTI’s drive to accede to power overtly or covertly, and it is difficult to ascertain the terms of the bargains beyond admitting the fact that such deals are usually one sided.

Then there are deals that have been made for securing majorities needed to form governments at the centre and in Punjab, to have a say in Balochistan affairs and to tighten the front against the PPP government in Sindh, the only province out of the PTI’s control at the moment. Some of the deals appear strange, to put it mildly. For instance, the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP) had to be humoured to secure its support to the PTI at the centre, support that was unconditionally available for reasons that are common knowledge. But how does the PTI become entitled to a seat in the Balochistan cabinet with only a single member in the assembly? This generosity of BAP may be justified by giving other single member parties in the assembly also a ministerial post each.

The PTI-MQM deal also causes considerable surprise. Imran Khan might have forgotten his full-blooded diatribes against the MQM and MQM leaders may also choose to forget them for the time being but the people cannot expunge the relevant record from their memory.

That the PTI has decided to forge an aggressive alliance against the PPP’s Asif Ali Zardari, the second target of Imran Khan’s endless tirade, is understandable. This is real politics. But how will the PTI keep its promise of freeing the people of Karachi of their bondage if it embraces the party he used to curse for all their problems?

The point to be borne in mind always is that the deals made before and after the polls may not be in the interest of the people or a democratic dispensation. For instance, concessions made to the quasi-religious lobby to an extent that a counter democratic ideological narrative can be developed will make the polity vulnerable to forces that would wish to establish a theocratic state. The results of such tactics are evident.

Likewise, alliances with big landlords will prevent the state not only from protecting the rights of the landless tillers of the soil but also from establishing social equality among citizens that is essential for creating a democratic order. How the new government will honour its compromises without further diluting the imperfect democracy remains to be seen.

Imran Khan had asked the electorate to give him a clear majority so that he did not have to depend on his coalition allies. To a considerable extent his prayers have been answered and he doesn’t need much support from his coalition partners. But he is continuing to gather allies, partly to save them from drifting towards other fronts and partly to be able to nibble at the opposition that appears to be quite strong at the moment. The nuisance value of PTI’s new bedfellows will depend on the availability of better opportunities elsewhere, and since no greener pastures are at present visible, they will not be able to pose serious problems to the government. Yet the political structure will not be as stable as a state that cannot avoid taking unpopular decisions needs.

The obstacles the country’s political culture raises for parties that are inclined to behave democratically need not be ignored. The haste shown by the PTI to catch the independent winners of seats in the Punjab Assembly, and offset the PML-N’s slight superiority was not liked by some democratic-minded people. They wanted Imran Khan to follow, or at least acknowledge, Nawaz Sharif’s 2013 decision to not join Maulana Fazlur Rahman’s bid to resist the PTI’s efforts to form the government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or his decision to let National Party (NP) to take the first turn in office in Balochistan instead of his own party. They further argue that the PML-N was apparently not in a position to form its ministry in Punjab even if invited to do so. But perhaps the PTI realised that this was no time to indulge in political chivalry, and it was risky to leave the independent members free to be put on sale in the market.

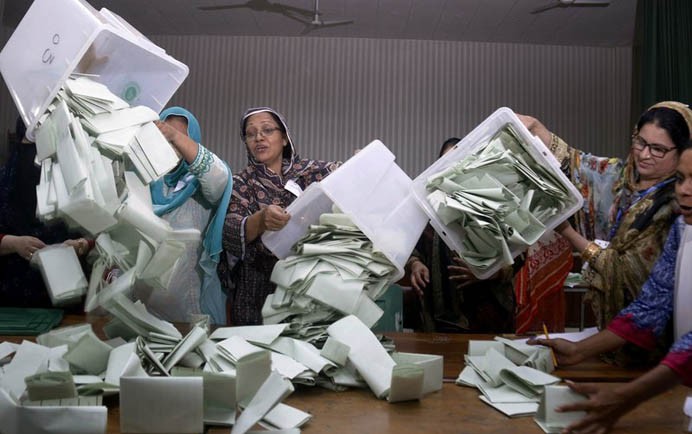

An even more serious challenge to the democratic character of the polity is about the questions regarding the legitimacy of the new dispensation. The situation might not have been serious if the losing parties and candidates were the only ones crying foul. The fact that thousands of people claim to have witnessed what happened after the close of polls, and that at many places the expulsion of polling agents and observers was neither a discreet nor a persuasive operation, has considerably enlarged the circle of sceptics. No less serious is the failure to get Form 45, the result sheet, signed by the polling agents, and putting it on the ECP’s website shortly after the ballots had been counted.

Imran Khan had won a well-deserved applause when he declared in his victory speech that the losers could get as many boxes opened as they liked. The pressure of those who are alleging rigging of the elections could have been blunted if that promise had been fully honoured but signs of second thoughts on the subject are unlikely to go to the credit of the new government.

The claim by NADRA that the Result Transmission System (RTS) did not break down, as was given out earlier, but that its use was discontinued has posed a serious threat to the reputation of the ECP and the credibility of the electoral process. Imran Khan knows perhaps better than others how strong the feelings of anger and frustration these disclosures must have generated in the opposition camp. The inevitable confrontation is bound to affect the government’s performance, and slow down the country’s transition towards a genuine, functional democracy.

If the ongoing inquiries and proceedings before the election tribunals do confirm manipulation of elections, two critical issues will arise. First, how will the bills for manipulation be paid? And, secondly, how will the government live with the crisis of legitimacy? Unfortunately, credibility of democratic institutions is hard to acquire and quite easy to lose.

The people seem to have become weary of confrontational politics but their wishes for good and orderly governance will not be realised unless the doubts about the fairness of the electoral process are set at rest. The interests of the new government and the ECP, and the cause of democracy demand that all questions related to the alleged manipulation of the elections must be resolved as early as possible to the satisfaction of the people, the losing parties/candidates may never be satisfied. Otherwise the people will lose hope that a fair election can ever be held. They could also lose all interest in democracy, in politics itself.

Correction: In the article on Deomocracy under strain by I.A.Rehman the reference to PTI-BAP understanding was based on earlier reports.The situation has changed and PTI has now five seats in the Balochistan Assembly.The oversight is regretted.