Reading two old novels to conclude that change only takes place when politics is intertwined with literary education

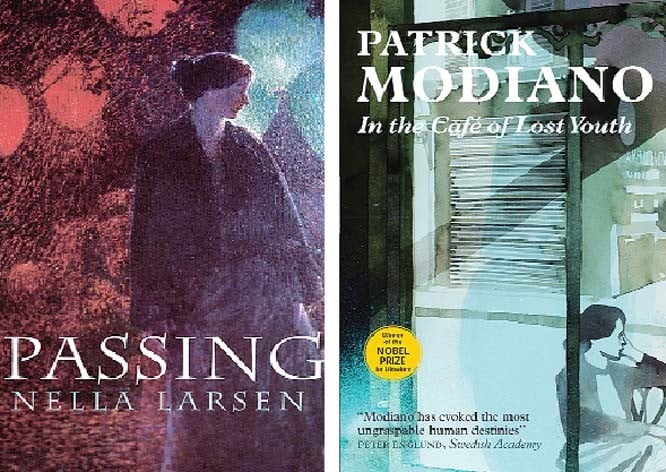

As luck would have it, I managed to read two very short novels just when my family, cousins, their children, friends, and I were gripped with the election season in Pakistan, the slogan of ‘change’ being shrillier than others. Both the novels engage with the notions of ‘passing’ and ‘change.’ The first novel Passing (1929) is by Nella Larson, an African American writer, who wrote during the Harlem Renaissance era. The other novel In the Café of Lost Youth (2007) is by Nobel Laureate, Patrick Modiano, translated into English in 2016 exploring the existential and bohemian mindset in Paris of the 1950s.

Larsen’s characters weigh the pros and cons of being fair enough to pass as white in social and/or marital settings at the risk of being exposed one day. In Passing, two women friends meet after many years in a setting where both pass as white. The narrator is married to an African American; the other woman to a white man, unaware of the African side of her genetic history. With some trepidation, the narrator allows her friend to enter her circle -- dinners and dance parties -- to re-connect with her black roots, when her white husband is away on business trips.

Modiano’s novel, on the other hand, recreates a time when Parisians (and other French people as well) are trying to pass as someone other than themselves in the post-Vichy France, condemning others as collaborators while indulging in forgetfulness and faking personal histories. The novel is divided into four chapters centred around a young woman called Louki, a name given by one of the fixtures at the Café Conde. The first chapter is by a student observing Louki initially sitting alone and then gradually being inducted into a wider group of students, artists, and thinkers. The second chapter is by a detective that Louki’s husband (twice her age) has hired to track down his missing young wife. The detective, at the end, decides not to inform the husband. The third chapter is by Louki herself. The final chapter is by Roland, her lover. Café Conde is a place where you can reinvent yourself without the burden of past.

Both novels end with the subject falling off a balcony and dying.

Just as there’s a phenomena of racial passing, there are other kinds of passings mentioned in literature as well, be it a Hindu in one of the several partition stories trying to blend in as a Muslim in Intizar Hussain’s Shahadat ; or a nervous person travelling by a bus in Husain’s Hamsafar, classics which should be taught in every literature class in Pakistan, as it questions the decision to migrate, one’s slippery identity, false history, and the need to blend in. His Hindustan se aik khat is also a remarkable treatment of how certain members of the Muslim polity felt the need to concoct histories privileging foreign lineage over native roots just as the British had cast them. Stifling conditions in a given society force people to pass, just as societal suffocation makes people itch for change, often, without understanding its contours.

What kind of a change are Pakistani voters, who by now have voted Imran Khan in, asking for? Even when it is being openly acknowledged that the military played a crucial role in streamlining Khan’s victory allegedly by intimidating press, politicians, and other sectors of the society, not to mention the probable role it played in encouraging the formation of Tehreek-i-Labbaik, denting Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s vote bank.

The two novels, one by a woman of African American lineage, the other by a white man of French origin, flesh out the movements of women in a given time and space, their agency and intellectual reach, despite their tragic finale. If Rafaqat Hayat’s Mir Wah ki Raaten is any indication of how stifling public space has become for women in the rural and urban landscape of Pakistan, any real cry for a change in Pakistan must begin with allowing women to regain control over their freedom of movement and decision making. Amused and horrified, as I watched my relatives and their friends (predominantly men) debate the election favourites from both ends, it was evident that most of them were politically educated yet lacking in literary education, when both are intricately linked to each other. If one is lacking in literary education, one’s understanding of politics will be without nuance. Any meaningful change in Pakistan will have to start with allowing discourse and visibility to women.

In a country such as Pakistan which continues to suffer from structural backwardness due to lingering feudalism, military dictatorship, and entrenched sexism, the recent election and its outcome does not auger well for women. If the new government has been brought into power by "the youth", how come the national political scene is so completely dominated by men? The world outside home must be a horrendous place for women if they don’t participate in election rallies.

Pakistani nation is also going through the process of passing; especially our youth which has internalised itself as English medium and has conflated it with being modern. And since most of them doesn’t read native literature, which is the only mirror highlighting dark spaces and gaps in understanding, it lacks the ability to comprehend the larger picture of what constitutes change, or the process of modernisation. The nation has also embraced a false sense of history and mixed up identity. Only a confused bunch like us would use the logo of a soda drink-- the number one source of diabetes and obesity, not to mention osteoporosis -- for an enterprise of fake musical innovation and fusion.