Two competitions, one in the 50s and the other in the 80s, gave us Pakistan’s most pivotal national songs

The Pakistani project is the attempted homogeneity of a diverse set of ethnicities and cultures under the umbrella of Islam, with the aid of Urdu, to glue together a motley of Bengalis, Pashtuns, Baloch, Punjabis, Sindhis and Urdu-speaking Muhajirs. Instead of encouraging ‘unity in diversity’, something the Indian state learnt relatively quickly under the tutelage of its Prime Minister Nehru, Pakistan had a hard time justifying its existence without privileging a globalized Islamic identity over local histories and cultures. Since its inception, the Pakistani national song has thus existed as an effort at reconciling these contradictory forces.

Nadeem Farooq Paracha, the Pakistani cultural critic and pop historian writes in his piece for The Express Tribune (published August 14, 2017) that the first Pakistani national anthem was written by Jagannath Azad, a Hindu poet, and aired on the midnight of August 14th 1947. This controversy was flamed in 2004 by Pakistani bloggers. Paracha’s article also links to a 2011 version of this song from Radio Pakistan’s YouTube page. There is no available record, however, of the original version of the song. Paracha claims that Azad’s anthem ‘stopped being aired by Radio Pakistan after Jinnah’s demise in September 1948’, making it sound like a deliberate conspiracy. The truth is that the large-scale search for Pakistan’s national anthem started while Jinnah was still alive. Had he meant Azad’s song to be the official anthem, as the Governor General of Pakistan he could have intervened when in early 1948 a Muslim South African A R Ghani offered prizes of Rs. 5000 each for the people who would compose and write Pakistan’s national anthem. This offer was taken up by the government and in June 1948 announced to the nation through government press ads. While it is hard to deny the thrill in the symbolism of a Hindu writing the Islamic nation’s national anthem, the truth can sometimes be less exciting.

While A G Chagla’s tune was approved in 1952, a nationwide search for lyrics was set into motion by the National Anthem Committee. A total of 722 submissions were made. The final two came down to Hafeez Jalandhari and the poet Arzoo Lakhnawi, but Jalandhari ran away with the prize. Ironically, much before the national anthem process was set into motion, Jalandhari had written and composed a different anthem and submitted it to Liaquat Ali Khan. That, however, did not get approved. This earlier attempt is recorded in Kuliyaat-e-Hafeez, but it lacks the gravitas and spirit of his later, far more Persianized effort. It goes thus:

Another fallacy about the national anthem is that it is in Persian. While it is in heavily Persianized vocabulary, it can be understood by speakers of both languages. The reason for this seemingly verbose style is that the tune came before the words. Famous poet Qateel Shifai writes in his autobiography that he was one of the poets the government sent the tune to, but when he heard it he was deeply disheartened; there was no way he could write lyrics to such a difficult tune. Jalandhari managed to create something regal out of it, harking to Pakistan’s Mughal-Persian heritage.

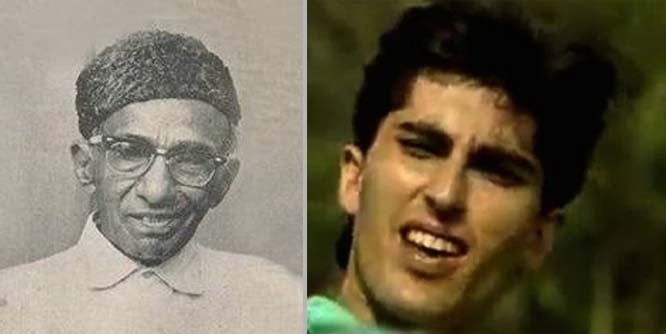

Another pivotal patriotic song that also became a part of the Pakistani cultural lexicon through the format of a competition was ‘Dil Dil Pakistan’. In 1987 PTV announced a competition between its five local stations, asking each to submit an entry for a national song for August 14. Every night before the 14th a new song was aired from each station. The national-songs great Sohail Rana’s entry ‘Deen zameen samandar sehra’ from Karachi station, sung by his prodigy Mona, seemed poised to win till one night four good-looking young boys clad in jeans appeared as Islamabad station’s entry and took the nation by storm. Although Paracha says in his piece that this video had ‘outraged the censors who refused to allow the song to be aired on PTV’, little of this was conveyed to the watching audience. PTV declared the song the winner of the competition.

Rising above the din of military glorification, religious superiority and pastoral romanticization, the best Pakistani milli naghmas have been ones that urge a tempered patriotism, more in step with the country’s one-step-forward, two steps back trajectory in its 70 years. Shehnaz Begum’s ‘Sohni Dharti Allah Rakhay’, one-song-wonder Ifraheem’s ‘Zameen ki Goad Rung Se Umang Se Bhari Rahay’ and in the more contemporary era Vital Signs’ Tera Karam Maula’ and Strings’ ‘Mayn Tau Dekhoon Ga’ managed to strike the right balance between hope and caution.