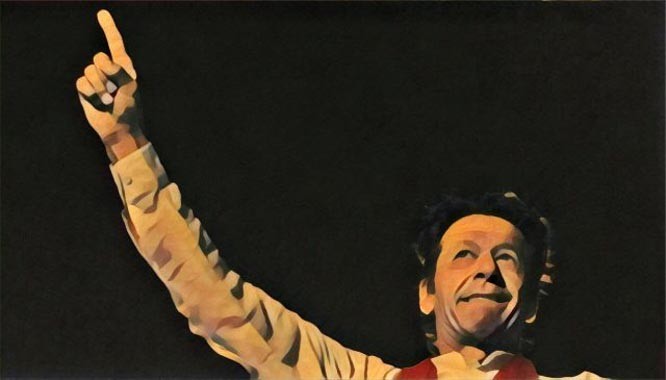

Based on media reports, the ascendance of Imran Khan has not sunk in well with many. Incessant doubts are being cast on his electoral success. He is branded as a stooge of the establishment. He is villainised, by his opponents, as an opportunist, and is considered not much different from other avaricious and power hungry Pakistani politicians.

Khan’s detractors claim that the recently held elections were stage-managed by the army to ensure he edged past the PML-N. The aim was, Christian Fair writes, "to vanquish its [PTI] bete noir, Nawaz Sharif, and obviously his party".

In the same article, titled ‘Imran Khan: Another Act in Pakistan’s Circus’, carried by The Diplomat, Fair states, "Pakistanis went to the polls thinking that they were electing a new prime minister. In fact, the choice had already been made for them. The army resolved to have Imran Khan elected as prime minister."

Post-election analyses focus on allegations of massive rigging and disallowing PML-N a level playing field in the run-up to elections. Fair proposes, "PTI is an acronym for Pakistan Turncoat Industry" not Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf. Personally, I find her criticism to be preposterous.

In her article, ‘Pakistan’s Promised Day?’ that appeared in The New York Review of Books, Rafia Zakaria denigrates Khan’s alliance with Fazlur Rehman Khalil, a pioneer of the Afghan jihad and founder of militant outfit Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, and the KP government doling out a huge grant of Rs277 million rupees to Darul Uloom Haqqania. Where this critique will appeal a liberal, moderate person, a student of political science must ask, what option does the state or the newly-elected leader have but to invite such actors into the mainstream?

The other options are: all-out state action, as the one conducted against Lal Masjid, and ignoring the militant elements, hoping one day they will fizzle out themselves. The Lal Masjid operation has shown that force is not a viable option. Similarly, pretending the militants do not exist is hardly the right approach. Therefore, in my opinion, the only option left to mainstream parties is to incorporate the supra-state actors, like Maulanas Fazlur Rehman Khalil and Sami ul Haq.

Imran Khan and his party have adopted the right approach to incorporate all sections of society into the political mainstream. The state has made mistakes in the past that cannot be ignored now. As a famous Urdu couplet goes: yeh jabr bhi dekha hai tarikh ki nazron nay/ lamhon nay khata ki thi sadyon nay saza payi (history hath witnessed the oppression of this state/ a few moments had erred, but centuries bore the punishment).

These critical analyses underscore an important concept of the idea of agency. Simply put, the democratic electoral exercise presumes that a voter possesses agency, and the whole idea of adult franchise is based on the right of the individual to exercise that agency. Khan’s critics, like Fair, accuse him of having benefactors in the security establishment of Pakistan; implying that the voters have been denied their right by somebody else appropriating their agency, and exercising it on their behalf.

Or, perhaps, these critics believe that pre-poll rigging denied agency to PML-N voters. They argue, if Nawaz Sharif had not been disqualified, his voters would have elected him again, and this would have complicated matters because denying Sharif agency in the political process would have been impossible in such a scenario. Also, they argue, Hanif Abbasi’s disqualification a few days before the election denied his supporters the right to exercise their agency.

In the final analysis, a mature and powerful polity, like the Pakistani public, cannot be denied agency. In recent memory, the referendum that General Musharraf conducted (which was wholeheartedly supported by Khan) denied agency to people. However, it is too simplistic an argument. Did the people of Pakistan decidedly oppose Khan being elected? Has he never won a seat before? Does the PTI not have several thousand voters in each constituency? If the answer to any of these is ‘no’, the PTI supporters have indeed exercised their agency -- and the significant number of votes polled for all opposing parties show that their voters also exercised their choice.

Therefore it can be argued that the agency of voters for Khan overcame the agency of voters for other parties. Such an election is not a dubious one, rather a democratic exercise of the agents of democracy, the public, to assert their right to demand a change in the status quo.

Imran Khan cites the Muslim state of Medina and the secular state envisioned by Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah as his model states. His detractors, like Zakaria, see this as an inherent contradiction in that he tries to reconcile two opposing traditions. However, it is a fact of Muslim history, especially in the subcontinent, that the horizontal and vertical models of history are seen to overlap.

The vertical model necessitates that the Muslim look at the past, the ideal state of Medina, as the ideal model. The horizontal model necessitates that the leader looks at his contemporary era to emulate a socio-political model. Since there is a paucity of workable socio-political models in the contemporary Muslim world, the Muslim world has to look towards the West for examples.

Thus, the vertical and horizontal forces of history collide. This contradiction appears clearly in Jinnah and Iqbal, who both envisioned a Muslim nation-state, perhaps a contradiction but a possibility made incumbent by the processes of history. What seems an impossible and unreal ideal for Khan to realise is really the model for Pakistan that its founding fathers had envisioned.

All I’m arguing here is we have accepted far worse in the past. The change has been brought about by a new demographic of voters, a far more conscious and aware generations than any previous one. Rest assured, they will hold Khan accountable far more effectively than all the naysayers.