The 69 years old Majlis e Taraqqi e Adab library has been faithfully playing its part in advancing the Urdu language; it is home to over 28,000 books, many of these being translations

I have always loved the scent of old books. When I recently visited the Majlis e Taraqqi e Adab library, on Club Road, its ancientness struck me, and more so because of the very same reason.

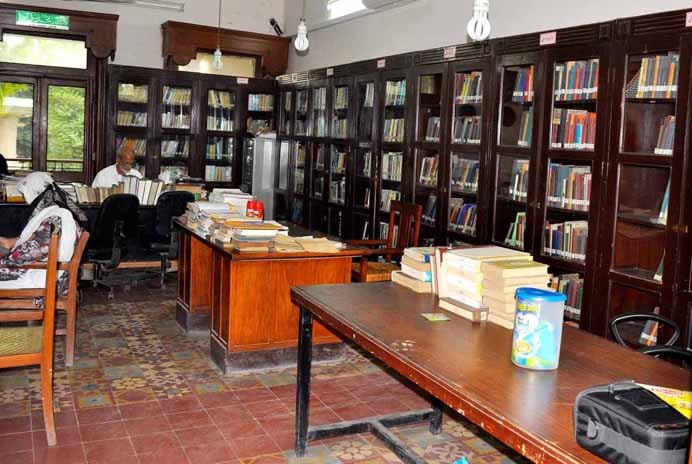

I noticed a tall ceiling fan and a hanging bulb illuminating the spot where the editor sat. Stacks of books morphed around him, making him a part of their stories and histories. It was overwhelming to find out that the library contained as many as 28,000 books. The walls were emblazoned with Quaid e Azam’s pictures, and each window reflected the swaying branches outside which had loped the building from all sides.

The space was encircled with wooden bookshelves stacked with neatly bound books, inviting everyone, or anyone, to come and have a look. Life seemed to come to a standstill in this museum of books. The tranquility of the place made me forget about the chaos of the world. The calm and slow, rhythmic movements of the inhabitants exhibited a complacency that I had yearned to achieve.

It is no place for ordinary people; it is visited especially by scholars, teachers, PhD students, and those with a penchant for indigenous literature.

Majlis e Taraqqi e Adab (or the board for advancement of literature) was first created in 1950 in an attempt to preserve Urdu literature and retain a Pakistani identity that is associated with the language. Initially. it was named, ‘Majlis e Tarjuma,’ as it was solely responsible for translating Arabic, Persian, and English texts into Urdu to make them more accessible to the public. However, it was rechristened in 1954. The government backed up this initiative by providing funds. As a way of encouragement, the pioneers decided to award the best written story or literary piece in Urdu magazines every year.

The institute publishes books of a variety of genres and languages. It is surprising to know that out of all the books published, 90-95 per cent are mere translations of treatises based on a plethora of subjects like science, philosophy, religion, mythology, history and politics. The collection also includes critical essays and research papers.

I collected a range of information from the director and editor of the institute’s magazine, as each one of them provided information about their respective subjects. Their love and devotion for the place could be felt through their words, as they explained the aim and purpose of the institution. They are committed to promoting Urdu literature and as a result are fulfilling an essential duty to the nation.

The editor, Mr Qarshi, shed light on the marketing process and how they had managed to reach out to their various customers. The process was simple: it entailed sending bulks of books to bookstores and Urdu Bazaar which act as intermediates. Exhibitions held at Expo Centre and different universities help promote the growth of literature. However, they did not issue books.

While talking about their recent publications, Qarshi’s tone shifted from matter-of-fact to that of reverence as he showed me a rare collection of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s letters. There was a plethora of literature on Sir Syed, as if it was a token of appreciation for his efforts. It was all due to the relentless efforts of a scant number of people who make it accessible to the people.

Dr Tehsin Firaqui, Director, Majlis e Taraqqi e Adab, gave a brief introduction of the place, and highlighted some of their achievements. He was conscious about the aim of the institution as he repeatedly said that they could not surpass the boundaries within which they were required to work. He admitted that the institute had not produced as prolific work for the new generation as it had for scholars and those engaged in the field of Urdu literature.

Firaqui gave a brief account of how the institute came into being and who laid the foundations. Like a scientist who systematically explains a certain experiment, he laid out the objectives that included translating and disseminating classical literature. He said that the Board of Governors makes important decisions, offers suggestions, sanctions their projects and facilitates them.

Dr Firaqui is well versed in the field of literature. He was a walking storehouse of knowledge as he recalled the names of those who had translated renowned English books of philosophy, history and politics into Urdu. He especially mentioned Ghulam Rasool Mehr who had translated Study of History by Toynbee.

The Golden Bough, a book of mythology written by James George Frazer, and Stray Reflections authored by Allama Iqbal, are among the books translated by Pakistani scholars.

I was amazed to learn that this year alone the Majlis had earned Rs2,724,000 from the sales of the books. I felt reassured for something that I never knew needed assurance. Urdu is still home for the people of this soil, and people like him will keep on working towards its preservation and propagation.

The 69 years old institution has been faithfully playing its part in advancing the Urdu language. We need people who are motivated to preserve our national language and identity, who would wear it as a badge of honour rather than take it for granted. The endeavours of these people are worth appreciating as it is through their efforts that our national heroes are alive and thriving.