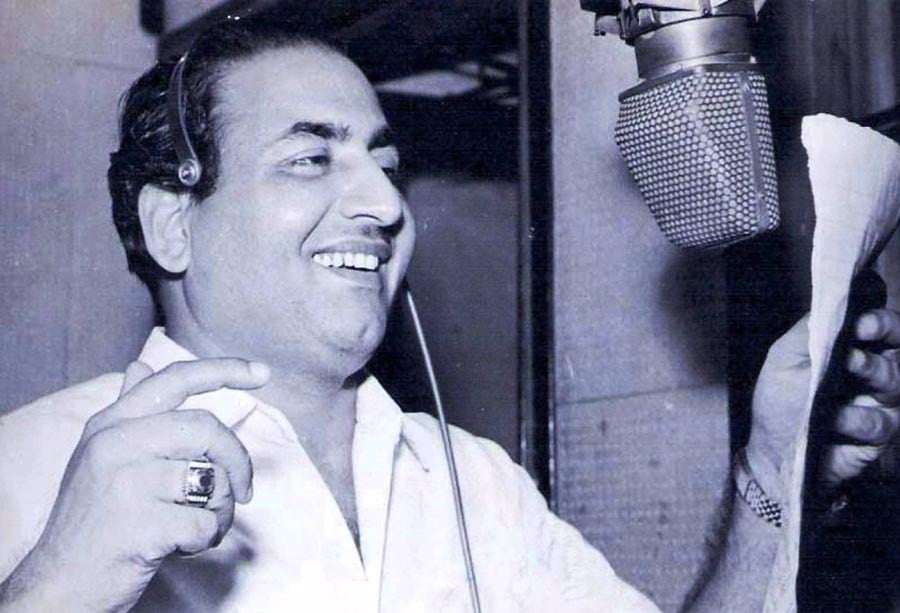

Mohammed Rafi saw music transition from the purist to the popular, yet he hardly ever tinkered with the essentials of the musical tradition

As the procession of film music continues, it can be said with a degree of surety that Mohammed Rafi along with Lata Mangeshkar constitute its middle phase.

Film music since its inception has been an eclectic form. It drew from all sources, initially from the lok and then the kheyal, thumri, bhajan and qawwali. Later, the western classical tradition influenced it immensely, and in the second half of the 20th century, it drew from the emerging jazz and rock & roll forms. Now rap has been permeating its various innovations as computer-generated sounds are also shaping its timbre and intonation. Its use of instrumentation too is very open.

Unlike the kheyal and dhrupad, it did not stay faithful to the raag and the bandishes were reinvented for its consumption. It mostly relished the song format and so the mudh lai was usually extant. The lyrics assumed special significance and these were contemporised to be easily understood by the lay listener.

While kheyal, and before that dhrupad, had been great examples of khula gana, as indeed were qawwali and lok forms, probably the theatre as it evolved in the 19th century in the subcontinent tied the bandish to the character and situation. But even then the scope of improvisation was immense as singing was live and everyone responded to the feedback from the audience. The audience actually came to the theatre more for music than for characters, plot and situation.

The cutting of the 78rpms probably also set the time limitation of the number; this was followed into the film format as playback was introduced in the early 1940s. The vocalists and instrumentalists, as indeed the composers, had to acquire the skill to do so much in that time duration. The format was thus laid down as a bit of alaap thrown in first, followed by an asthai and two antaras and a couple of interval pieces inserted.

This transition can be dramatised by quoting the example of the ustads. Since it was also considered important to record the ustads, they were also made to squeeze into this time slot and had to totally reorient themselves to three-minute duration. They were used to khula gana, without any time limit and that too before an audience. Most were not able to make this instant transition and the recordings we have in the archives, as told by many who heard them live, do no justice to their art and reputation. Some even refused to be recorded altogether.

Mohammed Rafi and Lata Mangeshkar seemed to be links between the two phases. Film music looked for its first real male singer and found one in Kundan Lal Saigal, who made his debut in the early 1930s, and then dominated the next 15 years till his untimely death when barely in his 40s. At about the same time in the mid-1930s, Noor Jehan also made her debut, maybe then in her early teens, but soon became the top female vocalist of this new genre.

It can be said that Noor Jehan and K.L. Saigal with others as well formed the first phase of this new genre.

After the death of Saigal, the field was left wide open and a number of male singers rushed in, like Mukesh, Talat Mehmood and Mohammed Rafi, to fill the void. Rafi proved to be the most popular because of his greater versatility.

Born in village Kotla Sultan Singh in the Punjab, Rafi moved to Lahore, where he spent the formative period of his life in the city working as a barber in a family enterprise round Mohni Road and Bhatti Darwaza.

But his heart lay in music. He moved and mixed freely with the music circles, picking up intricacies of music from a number of well-known vocalists and instrumentalists of Lahore. The music scene was quite vibrant and people like Jeevan Lal Mattoo served as connoisseurs and patrons of music in the city. It was in these baithaks and soirees that Mohammed Rafi picked up the finer aspects from ustads like Abdul Waheed Khan and Chotte Ghulam Ali Khan.

Feroz Nizami introduced him to radio in Lahore before he made his film debut for Shayam Sunder’s Punjabi Film Gul Baloch in 1944. He moved to Bombay and was given a break by Naushad in film Pehle Aap, the same year.

Since music was making a transition from purist tradition, cultivated by individual patrons and super virtuosity of master musicians, to a more popular level, hemmed in by the limitations of the market and disparate popular expectation, the music composers did a fine job of not letting go of the essentials of their local musical traditions. Rafi lived in that phase and despite the innovations and changes never tinkered with the essentials of the music tradition. Though he was noticed in Anmol Garhi and sang alongside K.L. Saigal in Shah Jehan , both under the music direction of Naushad, it was his duet with Noor Jehan in Jugnu, composed by Feroz Nizami, that catapulted him as a serious contender to fill the vacant slot of the leading male vocalist. He truly arrived as an individual vocalist in Mela, where again he sang under the musical direction of Naushad.

Rafi was nourished in the classical tradition. When the film music moved into top gear with greater input from the enriched musical heritage, Rafi had the credentials to be its chief exponent. In Baiju Bawra, he demonstrated his virtuosity and range, and in Piyasa, the evocative power he could bring to the lyrics. Though he did make a partial transition to a more youthful and playful style, as in Jangli, that demanded a different kind of musical ability, he was too closely wedded to the classical tradition to wander too far from it.

Mohammed Rafi died on July 31, 1980.