Those who claim to cleanse Pakistan of wrongdoings must start with declaring the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto sentence null and void

It is perhaps time now to say this: that until the unjust punishment of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto -- accepted as judicial murder by all and sundry -- is declared null and void, a curse will keep visiting our beleaguered politics. In the last 37 years, this curse has developed into a national guilt. This guilt is now entrenched in our national psyche -- reminding us repeatedly that the powerful can physically eliminate the popular in the name of law.

This judicial murder only shows how a hypocritical military dictator could outmanoeuvre an intelligent and talented politician by the sheer power of the state, and with the help of a pliant judiciary.

The demise of Bhutto brought an end to the possibility of political change through the power of the people. Isn’t it tragic that the judicial murder took place in broad daylight, in the presence of a democratic constitution? No judge or general (both take oath to abide by the constitution) has come out in the last four decades to openly say that it was wrong to kill Bhutto and that they, the people, were saying this to clear their conscience.

It was only logical then that might has been considered right ever since, strengthening the longstanding colonial precept -- one cannot challenge power, one can only surrender and submit to it.

The society’s confidence in the power of people has shattered since Bhutto’s death. Unfortunately, the murder in Shakespearian terms was "the most unkindest cut of all" to a budding democratic nation that had started reposing full faith in people’s power. Since then, foul has become fair, and constitution, law, justice and fairness have become hollow terms.

Principled nations keep a record of their high and low points. They take pride in their collective and individual achievements, and are ashamed of their wrongdoings. This nation’s soul is surely guilty of the judicial murder of an elected prime minister.

Some conscientious British intellectuals feel guilty about their country colonising India and other parts of the world. This British remorse reflects the British psyche of national guilt.

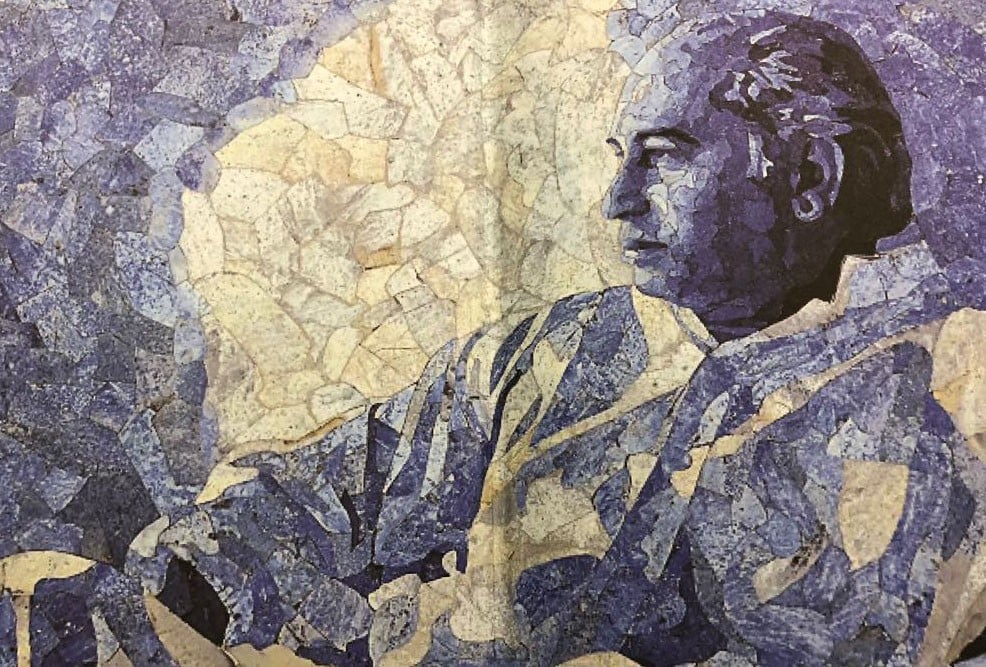

Here the guilt over Bhutto’s death has not diluted with time. As a leader, Bhutto still remains far above others in stature. He was a friend of the 20th-century philosopher, Bertrand Russell, who revolutionised the social and political thinking of the world. He could face US statesman Henry Kissinger and President Richard Nixon as an equal. His close friendship with Chinese leaders Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong consolidated Pakistan’s relations with China. He was equally close to world luminaries like Indonesian President Sukarno, Libyan revolutionary leader Muammar Qaddafi and Saudi King Shah Faisal.

Bhutto became a mythical character not because he was a world-class mover and shaker but because of the way he fought back a dictator. During his trial, like Greek philosopher Socrates, he respectfully called judges "Me Lord" to keep the philosophy of justice alive, though he knew well that they were mere puppets in the hands of General Zia. He showed extraordinary valour, unprecedented determination and true commitment to his principles during his jail days.

Those who claim to cleanse Pakistan of wrongdoings must start with declaring the ZAB sentence null and void. Any doctrine or party manifesto trying to circumvent Bhutto’s reality, this deep-rooted guilt, will fail to heal this wound.

Thirty-seven years after the "murder most foul", the ‘doctrine’ has decided to demolish the political generation of Gen Zia’s 1985 party-less polls. It claims this generation has criminalised politics in the country. Intellectuals and policymakers are constantly reviewing Zia’s Afghanistan policy and are talking of adopting a policy of non-interference. His extremist policies are gradually being amended. Today, the nation repents his policies and their worst consequences.

Isn’t it, therefore, time to revisit the Bhutto case, like all other decisions of that dark era, and pave way for a state which is judicious and neutral for all stakeholders?

How can the powers-that-be be considered neutral unless they openly denounce their mistakes? How can we believe that judiciary is independent unless it openly admits that Bhutto’s sentence was politically motivated?