Is Pakistan’s culture homogeneously identifiable?

Culture as a phenomenon has fascinated theorists from various epistemological traditions. Historians, literary critics, philosophers, anthropologists, as well as sociologists have tried to decipher the meaning of this widely used term.

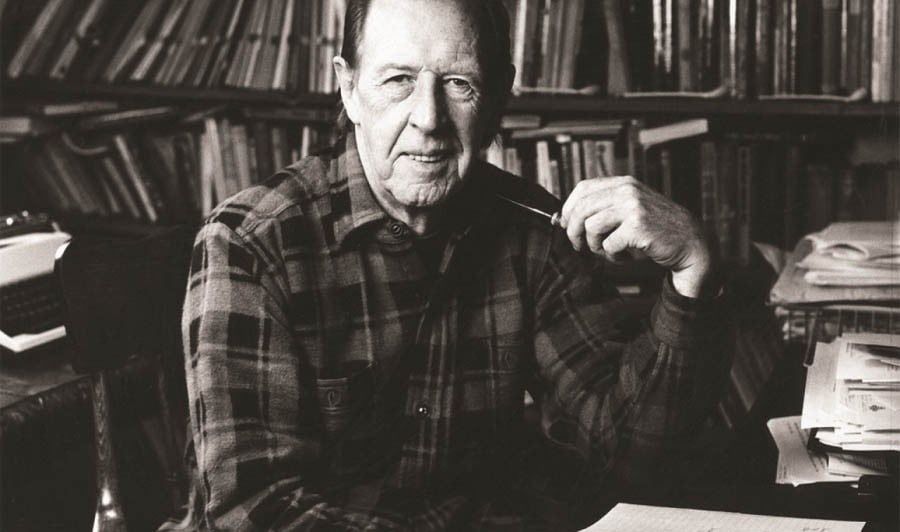

Raymond Williams traces the epistemological shift in the meaning of the term ‘culture’ in the late 18th and early 19th century. Before this historically crucial period of the Industrial Revolution, the term meant primarily the ‘tending of natural growth’, and the meaning extended to imply the training of humans, as if their ‘natural growth’ needs to be ‘tended’ or ‘controlled’.

In the period under consideration, Williams notes that the word ‘culture’ took on four additional meanings. The first was ‘a general state or habit of the mind’, an idea that posits a ‘cultured’ person as a socially perfect one. The second meaning was ‘the general state of intellectual development in a society as a whole’. This idea has a crucial link with the ideas of modernity and ideology in a postcolonial society, as I will explore. The third meaning that the word ‘culture’ took on during this period was ‘the general body of the arts’, and the fourth meaning was ‘a whole way of life, material, intellectual, and spiritual’.

Most Marxist criticism argues for the development of culture as a reaction or response to the changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution in the means of production; whereas Williams argues that the changing understanding of culture was a response to the changing personal social relationships during the Industrial Revolution, and it is this aspect that is most important. Elsewhere, Williams argues that culture is ‘ordinary’, an observation that implies that culture is something that relates to lived experience and is therefore both traditional and creative. To sum up a complex idea, Williams implies that a culture survives by being rooted in tradition but also by adapting to evolving situations. When Williams posits that there are no masses, but only ways of seeing people as masses, he highlights the role played by ideology in shaping the experience of a people.

This brings me to my main assertion: culture, as understood in postcolonial Pakistan, is a largely undefinable and unquantifiable commodity because of the ideological state apparatus that attempts to homogenise cultures in Pakistan. It is also important here to state that an onto-epistemic rupture occurs in this process. The onto-epistemic rupture of culture implies that the lived experience of culture is different from the way culture is perceived or theorised. In simple words, I wish to underscore the fact that the so-called homogenised, composite culture that dominates Pakistan’s ideological epistemes is not the same as the popular, every-day, ordinary culture as practised and lived by the people of the several ethnic, religious, political, and social polities that exist in the country.

In this context, I must quote Clifford Geertz who in his book The Interpretation of Cultures draws a link between culture and politics. According to Geertz, "culture is not cults and customs, but the structures of meaning through which men give shape to their experience", and "a country’s politics reflect the design of its culture". Culture generates meaning and is in itself lived meaning, not just the customs that are ritually practised. For example, the case of a ritualistic festival like Eid, practised homogeneously, is different from the lived experience of the regional mela which has its own specific tribal, plural, regional colour that varies from village to village, province to province, and community to community. The assumption that the ritual of Eid is a representation of culture is not entirely untrue, but when contrasted against the now banned mela of basant, it has less cultural value.

The specificity of basant, that originated in this part of the world, makes it more ontologically rooted, and it does not create any fissures between the lived experience of the people and their ideological makeup.

So, is Pakistan’s culture homogeneously identifiable? Is there one composite national culture that we can consider as representative of the people? For the answer to these questions, I turn to Mohsin Hamid, for as several cultural critics would attest, it is to our writers and artists that we must turn to for understanding the cultural trends in society. Art is an integral part of culture, and the artist represents the cultural tensions in a society. In a 2010 essay titled ‘Room for Optimism’, Hamid argues that unlike popular perception, we are a tolerant nation, and this tolerance arises from our great diversity. With the different ethnicities that co-exist in our society, as reflected in any classroom in any educational institution, there are also different and diverse cultures that exist simultaneously. The onto-epistemic rupture that I have highlighted earlier seems to be non-existent when we see Pashtun, Punjabi, Sindhi, Baloch, and Gilgiti students sitting in a class, and being friends with each other.

However, when we try to force on them the colonial heritage of a national language developed significantly during colonial rule, we try to impose on them what becomes a ritual. In our misconceived apprehension of the lingua franca English, we forget that Urdu too was colonially conceived and imposed, as Dr Tariq Rahman and other scholars have shown in their work. Urdu has its undeniably rich cultural heritage, but in the postcolonial state of Pakistan, that heritage has been reduced to a religious heritage devoid of its geographical and historical underpinnings.

This is precisely the onto-epistemic rupture that makes culture the exact opposite of what it is supposed to be, a theoretically conceived and enforced entity rather than a lived experience. Returning to Hamid’s important essay, the different parts of the polity, for all their heightened and exaggerated diversity, practise tolerance. Co-existence is our great strength; I must concur with Hamid.

I will now focus on the second aspect, which is the concept of culture as it exists across borders. The phenomenon of culture today cannot be divorced from the advance of globalisation. There are two paradoxical aspects to this particular phenomenon. On one level, globalisation has created a universalised market that believes in a unified cultural ethos, with democracy being a cultural pillar of that ethos. The international dominance of popular culture through Hollywood and Bollywood is an example of this aspect of globalisation. In a way, it becomes easy to theorise that our current onto-epistemic reality is a post-cinema, post-social media reality.

Conversely, at the same time, globalisation has also created great isolation and individualism in nation-states. The Donald Trump brand of exclusionism, also reflected intensely in Brexit and the Narendra Modi-Yogi Adityanath mode of Hindutva, is not an anomaly. It is, in my opinion, a natural product of globalisation. So, the lived experience of globalisation is increased human frustration at being isolated and insignificant, while the knowledge industry propagates that globalisation has brought the world closer.

It is also important to note that this onto-epistemic rupture of globalisation is similar to the one that colonialism had brought about in the colonies, especially in the subcontinent. As I have written at several other places, colonial modernity had two prongs: the so-called progressive advance of science, and the exclusionary rise of rarefied religious practice. Hamid considers religious diversity to be one of our great strengths, and a reason for optimism. Unfortunately, religious diversity in our culture gets overshadowed by radicalisation and fundamentalism. However, I argue that the roots of religious extremism are located in the colonial conception of modernity.

Read also: A historian’s approach to culture -- II

The work of scholars like Talal Assad, Saba Mahmood (late) and, in a slightly different sense, Jamal Malik leads one to conclude that South Asian Islam acquired its radicalised face through its interaction with Western conceptions of modern rationality. One might ask what does colonial modernity have to do with culture. I would like to argue that rationality was an aspect of ‘culture’ in Europe, reflecting European society’s general state of intellectual development at the time. Science was rational, and therefore it was considered culturally progressive to have training in scientific rational thought. The overwhelming and sweeping popularity of Darwin, Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche in the 19th century, and for most of the 20th century, was a cultural phenomenon, akin to the cultural dominance of ideas regarding race and gender today.

To be continued