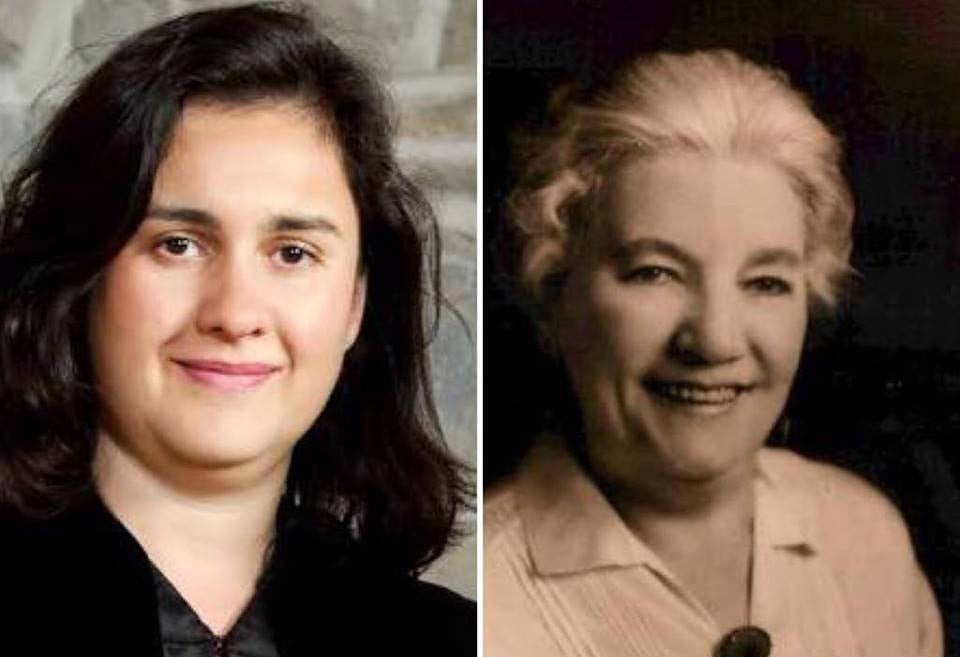

At thirteen, Laura Ingalls – pioneer girl extraordinaire – was my hero. My mother must have been so relieved - finally, a conversation that did not involve ‘Harry’ or ‘Potter’. Reading about her name being dropped from the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award by the ALSC recently therefore, should have been shocking. The only reason I can think of for not being utterly shocked at the dismissal of a childhood favorite was something I’d gained since my ‘Little House’ days: exposure. At nineteen I was convinced I’d read enough novels to last a lifetime and wanted something different.

In hindsight, Kamila Shamsie was as different as they come, and I should’ve been careful what I wished for.

At its very core, Shamsie’s Kartography’s tale of two separated best friends reuniting is a story about growing up in this strange land called Pakistan finding oneself at odds with a world that, until yesterday, had spun merrily away on its axis - but today, had been thrown into the dentist’s chair under a harsh, clinical light - with gaping cavities exposed.

She painted a picture of a city that I, with almost a lifetime in Lahore, recognised - because for all that the story is set in Karachi, Kartography is a tale of homecoming, about finding the familiar haunts changed and yet still, comfortingly, the same. It’s a love letter from a native, told from the perspective of a comfortable, sheltered child looking up in wonder, the adolescent seeing beyond the chaardiwari for the first time with a horizon just beyond her reach, to the young adult looking down at the cracks in the red bricks and paved roads and wondering just why they were once enough to form her whole world. Kartography is a love story in its truest sense. It is about learning the good and the bad and loving someone not despite the flaws, but because of them - and all that they have become as a result. It’s an identity crisis as Shamsie’s protagonist goes looking for answers she’s convinced will bridge the distances between people she’s loved her entire life. It’s also a story about racism.

In hindsight, it’s easy to see why it resonated - and stayed with me.

Growing up in Pakistan means an exposure to a brand of humour that doesn’t bother you until you’ve been exposed to a world beyond it - which means, by the time you’ve grown old enough to understand it’s wrong, it’s become ingrained in you, your language and your beliefs. As all children, I was as quick to believe my elders’ philosophies about an individual’s background determining their worth, as they were careless in dispensing them. As a teenager, with a fairly diverse group of friends hearing people, whose words I’d taken as Gospel comment on the general untrustworthiness of an entire province was jarring; a sobering wakeup call. As an adult, some of the horror at the blatant racism has dulled. I’ve repeatedly made my arguments, and I’ve gotten the expected response far too many times: It’s not racist - it’s just the way it is.

A father in a television show explained to his daughter: "We’re not racist - we’re black! And black people can’t be racist." It’s an argument that can be replicated in any Pakistani household today. For generations, we were the colonised. We were the oppressed.

We were the hungry minority on the outside looking in.

But, as Shamsie points out in that heartbreaking realisation in Kartography, when ‘Raheen’s realisation of the role her father’s racism had played in her own personal history rocks her world – that doesn’t make us saints.

I was a sheltered reader. Careful of their curious daughter’s voracious appetite for books, my parents kept a close eye on my bookshelves well in to my teens. As a result, I had little to no exposure to Pakistani literature beyond the poetry, children’s digests and stories handpicked by my mother - and didn’t know about Pakistan’s literature in the English language until the year I enrolled in college. Looking back, however, picking out the racist undertones in even my childhood favorites is far easier than I’d like it to be.

Too often, racism is considered a foreign (read: western) concept. Considering the news we read and see each day, it’s a conclusion that’s not difficult to come to - the angry American redneck spitting from the top of his truck as the person of colour (or, increasingly now, the Muslim) crosses the road, is a striking image. We’re sometimes so focused on the promotion of Pakistan’s ‘softer’ image that we forget it’s not as dissimilar from our country as we think.

Shamsie’s Kartography isn’t her only work to deal with prejudice. Salt and Saffron, with the protagonist’s fixation on whether or not her beau comes from the ‘right part of town’ had me in knots - it’s talks about the same prejudice, if only from a different perspective. But Kartography was what gave me my first clue that the niggling worry at the back of my mind wasn’t unfounded - that the people who raise us are wonderful, and brave and kind - but they too grew with blinders attached - and they’ve kept them on for too long. And her decision to draw parallels between her modern protagonist and the parents’ lives leading up to and after the partition of East and West Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh is akin to a long, necessary look in the mirror.

The sobering truth about racism and bigotry making it into our curriculum is that they lend themselves to the completion of a self-fulfilling prophecy - we are raised to believe that the ‘other’ is different and out to get us and somewhere down the line, we’re proven right.

As such, it’s not difficult to see why Laura Ingall’s name was removed from the Award - but not from school reading lists. Her stories are read primarily by children and young teens, forming their opinions about the world around them as they draw the same parallels I did. But they must always be read with context - that times change and what was considered acceptable before cannot be now.

Are her ideas about ‘savages’, ‘darkies and ‘Injuns’ jarring to read as an adult? Of course they are - they’re racist and disrespectful to generations who grew up as aliens in their own land as a result of such beliefs. Should the books have been banned along-side the name drop? No. Absolutely not. It’s very similar to Pakistani books I read today - in English and Urdu – whose stories contain enough ‘unnecessary sexual references, sexism and discriminatory themes to make me cringe with anger. It’s alarmingly easy, in those moments, to sympathise with authoritarians who decided the best way to deal with the past was to eliminate any trace of it. It’s a sobering realisation.

And so I keep reading.

I do so because writers - all writers - will write what they know. And these books, both the good and the cringe worthy, are what help me keep one finger on the pulse of my country, still evolving, still learning how to be anything but the victim of her past.

I keep reading because the racism in Pakistani literature is a white flag waving from the ruins of what were once fortresses, leftovers from a history we’ve been blind to for far too long.

Because yes, we were once the Dickensian orphans on the outside looking in, but despite changing times, we’ve clung on to our meagre beginnings like a security blanket, refusing to let go.

Because sometimes it takes a writer to throw an unpopular opinion in the middle of our drawing rooms, to rustle a few feathers and wake up the rest of us before we can form our own.

And because these writers are, in the only way they know how, putting a recognisable face on an unpopular opinion: there’s something rotten in the state of Pakistan, and rooting it out will take something stronger than banning books about uncomfortable histories- it’ll take the courage to read them, and write better ones.