Rozi Khan Burki and his team of volunteers have taken the challenge of reviving an endangered and indigenous language

Reviving an endangered indigenous language requires intense physical and mental efforts. Rozi Khan Burki, a senior officer at the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR), has taken the challenge and struggling to revive his mother tongue, Ormuri, for the past few decades despite his financial and material constraints.

Burki and his team of volunteers believe they can explore local unwritten laws, oral history, heritage and folklore. He has already dug out the historical background, reference books and other related manuscripts written in and about Ormuri.

And believe it or not, because of Rozi Khan’s unfeigned efforts, Ormuri has gotten a new lease of life. "Once on the brink of complete extinction, our language has started gaining popularity within our tribe."

"It has always been difficult to trace out the origin of a race, especially when documentary evidences are required," said Burki. Initially beginning with writing poetry in Ormuri, Burki managed to draw the youth’s attention towards the language. And what more could he have asked for. The youth followed into his footsteps and started holding poetic symposiums in their native town of Kaniguram, South Waziristan.

How it all began

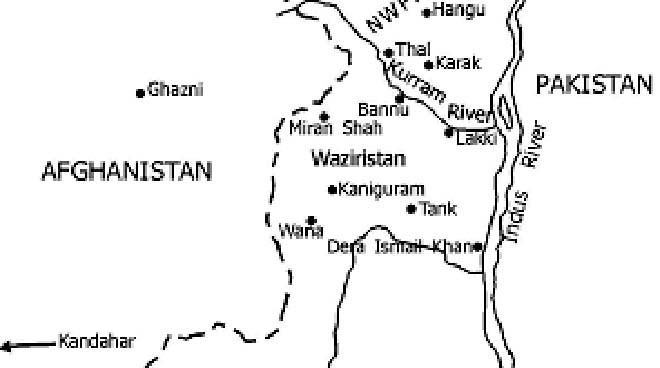

Ormuri is the spoken language of the Kaniguram valley of South Waziristan. The area belongs to the Burki tribe of Pashtuns but their mother tongue is not Pashto -- they speak Ormuri.

However, until a few centuries ago the language was a medium of communication in nearby vicinities of Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan. Later, the language got confined to a small group. Some people who hail from Baraki Barak, a district of the Logar province in Afghanistan, also speak Ormuri but their dialect is slightly different.

"Burki is purely a Pashtun tribe. We are Pashtuns. No one has the right to question our identity," stated the language preservationist, adding, that it is not essential for all Pashtun tribes to speak only Pashto.

In his article titled Dying Languages; Special Focus on Ormuri, Burki states: "The words Barakis and Ormurs are synonymously used for the same tribe, although the latter is comparatively new and not used by the tribe itself. They call themselves Brakees rather than Ormurs, and their neighbouring Pakhtoons (Pashtuns) use the latter name for them."

He adds that, "the language of Brakees is Ormuri, although the words Baraki, Bargista, Barakey have also been used for the language by historians and linguists in the past."

Burki maintained that Pashto and Ormuri are sister languages and have East-Iranian origins. However, both the languages have had separate trajectories of growth. The two languages have different sounds and etymology.

As per Burki, it is possible that the Pashtuns were multilingual at different points in time because many Pashtun tribes have their own local dialects of Pashto which have the potential to transform into separate languages in the future.

The first book

Even though Ormuri has been listed as one of the dying languages of Pakistan, there is still hope that it will survive. All because Burki managed to write the first ever book in the language. Titled Should we leave our language at the deathbed, the symbols and alphabets used in the book have mostly been taken from the Pashto script.

Burki says he will also soon be publishing Ormuri’s rules of grammar. And if that wasn’t enough, he has also compiled the phonetic transcription of a number of words along with the parts of speech. He is also working on an Ormuri-to-English and Urdu dictionary.

"The book also illustrates on prose, whereas a part of poetry has also been included as an attraction for young readers. This may help in streamlining the language." Moreover, he has tasked one of his team members to acquire the manuscripts of Ormuri’s grammar that have been preserved at the Islamia College University and Pashto Academy in Peshawar.

Speaking of books that have been written in the language, Burki mentioned that a book titled Qawaed-e-Zaban-e-Bargista was compiled back in 1881 by Ghulam Mohammad Khan of Charsadda -- he used to serve as the district inspector of state-run schools in D.I. Khan. The book comprised a part of Ormuri grammar. Unfortunately, the book remains unpublished till date.

Coming back to his own efforts, Burki stated that the team is using a special software to record and transcribe words as and when fresh words come to mind. So far, about 3,000 words have been compiled. Apart from this, Burki has also been working on a dictionary inclusive of 5,000 words. He informed that the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government has also entrusted him with a three-year project to prepare a textbook of Ormuri. "The initiative taken by the KP government commenced from August 2017. All the premier books are under print. We can even provide books for the Montessori level."

Threat to the language

In a series of interviews, a number of Ormuri-speakers told The News on Sunday that a majority of the Brakees moved to different parts of Pakistan, especially when the area was undergoing conflicts and insurgencies. After the turmoil, some of the displaced families came back to Kaniguram, but families which had shifted to urban areas and set up businesses were unable to go back to their native towns. This added to the risk of their already endangered language and culture going extinct.

Although the people said they still communicate in Ormuri inside their homes, they are compelled to speak in Pashto or Urdu when outside. "Our language is our identity, but when our children step out of the home they learn other languages like Pashto and Urdu," said Munawwar Burki, a businessman residing in Sohrab Goth, Karachi.

Zahid Alam Burki, a student of Karachi University, said his ancestors had kept Ormuri alive in oral form but in recent times the language has suffered an influence of other languages, especially after the displacement of Brakees from Kaniguram.

He pointed out that Ormuri is no more a medium of communication in Afghanistan because of the Persian influence on the language. "Ormuri in Afghanistan has almost died. Possibly, some mountainous people still speak the language but too many Pashto and Persian words are now a part of the language."

Zahid explained that the Ormurs of Peshawar have no idea about their real language because they adopted Pashto. The Ormurs have three villages in Peshawar -- Urmar Miana, Urmar Payan and Urmar Bala. The first two villages are located on the Urmar Jalozai Road, while the last one is located on the Shamshato Road.

He said a number of Burki families migrated from Jalandhar, India, after the Partition. Those families had shifted to India from Kaniguram and Logar, Afghanistan. In the 16th century they adopted Punjabi as their first language.

Can it be revived?

"A healthy language is one that acquires new speakers," said Prof Dr Rauf Parekh, a linguistic expert and senior faculty member at the Department of Urdu at the University of Karachi. "A dying language needs to be promoted among its native speakers. It is good to preserve a language by scripting books or tracing out the language’s history but these measures can’t prove fruitful in rescuing it," opined Prof Parekh.

He said that the North-West Pakistan has an overwhelming amount of linguistic diversity. The people of the mountainous regions speak around 30 languages. But sadly, no local researcher is interested in exploring the diversity, said Prof Parekh, adding, that foreigner researchers tell us that the area is a heaven of languages.

He pointed out that there are very few varsities which have separate departments for linguistics. The Urdu and English departments offer admissions but only for literature. The reason behind this is lack of linguistic experts.

However, Rozi Khan insists that he is not hopeless in the case of Ormuri. "When rare animal and plant species can be revived then why should we lose heart?" The Cornish, Welsh, Navajo and Hebrew are all examples of languages which were once on the brink of extinction. Today, these languages have thousands of speakers.

All thanks to BWA

The Burki Welfare Society was set up in 1987 by Nazar Jan Burki. It aimed at protecting folklore and promoting education among the tribe. In 2013, the society got itself registered as the Burki Welfare Association and started full-fledged work in 2016.

"The British had counted around 1,000 Brakees families living in Kaniguram, South Waziristan," said Nazar Jan. The area was known as Ismail Ghruna (Ismail Mountains) back in the 18th century. The area was named Waziristan when it was declared a tribal agency. Another reason was that the Wazirs and Mehsuds were more in number than the Brakees thus, the area was occupied by them.

BWA President Taj Alam Burki said the internal displacement of Ormuri speakers, and other tribes, in 2009, also affected the language.

Taj said the BWA is focusing on providing financial educational assistance to youngsters these days. It also provides health facilities to the community. The association has also made efforts to resettle Brakees in Kaniguram to save their unique language, folklore and heritage.