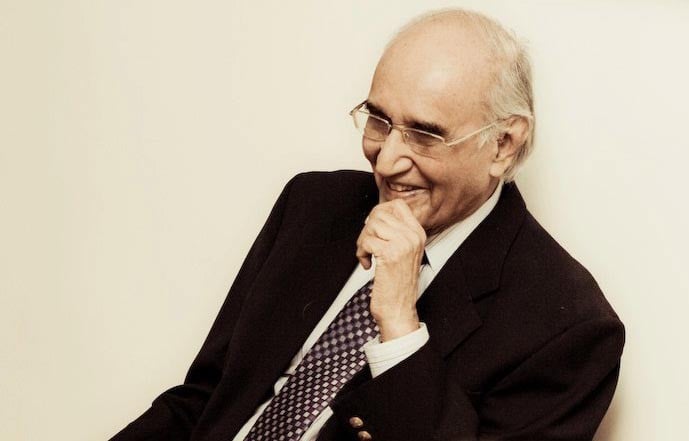

Mushtaq Ahmed Yousufi’s humour offered salvation and helped his readers come out of dark phases, rather than being emotionally dragged down by them

Mushtaq Ahmed Yousufi was not a very prolific writer. In all, he had published just five books over a lifetime that spread over almost nine decades with a writing life that was probably not more than fifty years. He started to write late or at least got himself published late with Chiraagh Talay, his first book, in the early 1960s. It was instantly noticed and earned him a place amongst the front rank of humorists of Urdu language.

It is said that the reason why Yousufi had not written more was because he was very fastidious and spent a lot of time dwelling on what he had written. He went over his work time and again, revising, rewriting endlessly, before the manuscript was sent to the publisher. The last book Sham-e Sher-e Yaraan (2014), for example, was published nearly 25 years after Aab-e Gum which hit the shelves in about 1990. Between the first book and Aab-e Gum, the other books published were Khakum ba Dahen (1969) and Zar Guzhast (1976).

As it is, there is not a very large collection of books on humour in Urdu and very few humorists come to mind. Probably, one can go back and focus on Ratan Nath Sarshar as the one who initiated humour in Urdu prose. Inspired by Don Quixote, he wrote in the picaresque tradition and his Fasana-e Azad is a kind of a survey of society and its character types through the eyes of both the main characters, especially ‘Khoji’ who leaps forward at everything, wanting to set the world right. This simplistic take on everything evokes laughter and creates humour.

Later, the writers increased in number though not considerably, with Patras Bokhari in the early part of the 20th century to be followed by more. Nearly all expressed themselves either in short stories, afsanas or in sketches on individual characters. Most of these characters could be identified by the contemporaries, thus adding a personal tinge to humour. Then there have been writers like Azeem Beg Chugtai (who was also hounded for the other writings which were not humourous), Farhatullah Beg, Shaukat Thanvi and Imtiaz Ali Taj.

Taj’s famous character ‘Chacha Chakkan’ was focused more on the character types that straddle this social order and can be a good barometer in assessing the health of this society. Even Patras Bokhari’s writings could be tracked down to character types, some of his own contemporaries, friends, pointing to the types that this social order has thrown up. Among his contemporaries like Colonel Mohammed Khan, Shafeeq Ur Rehman and Ibne Insha, Yousufi surely was the leading writer.

Actually, was a selection of the various papers, addresses and the presidential speeches that he had been reading or making over the years. It covered the time when he was in Karachi and then London where he lived for many years before moving back to Karachi on retirement. In addition to his addresses during that period, the collection also includes articles written earlier and not published in his collection of speeches.

It appeared that Yousufi was in great demand as a speaker because according to him, he had placed a moratorium on himself that he would not take part in programmes where he was invited as the chief guest and hence required to speak as well. Despite the self-imposed ban, the number of pages of his last publication was no less than 427.

What were the sources of Yousufi’s humour? He drew all his material from the society -- the situations, the characters, the barbs, the warts. It was rare that he created it only by commenting on the oddities of society, something that most humorists do. However, he may have done so only in small measure. The first was self deprecation. He created humour by belittling his own presence, whether it was in the shape of his physical appearance, to which aging was also added with the passage of time alongwith many other "unsavoury characteristics" that had not helped. Second was the choice of his profession, or some other interest that he had nourished, like the peculiarities of banking. Third were some people who were well-known.

It is common knowledge that well-known people are written about because they are famous and people know about them yet want to know a little more. These people with a certain reputation, a social face or a façade can be laughed at when the mask they wear comes off. If the mask is taken off totally, the writing can become vituperative but a partial removal or a momentary one can create humour. There were many people in the writings of Yousafi that, by the removal of the mask, caused ceaseless humour.

Another stock theme that caused humour was sex. Yousufi did not shy away from sex or the social mores that are sexual in nature, or tried to shield it through some hypocritical makeover. Yet another technique that Yousufi used with great freshness was to make amendments or changes in verses or sayings to suit the flow of his argument. As it is, verses in Urdu prose liven up the narrative and readers latch on to them even more. But by punning or making changes, the humour created was instant and tickled the funny bones of the educated reader.

He often also mixed some sad happenings like when his father had to leave his native city for having made a speech in the assembly about the Indian government attitude towards Hyderabad Deccan, and then his death on a railway platform while he was like so many others, struggling to find his mooring in the new country after migration. But it was the humour of Yousufi that offered salvation and upliftment, despite such great moments of despair. It helped him and his readers come out of dark phases, rather than being emotionally disfigured and dragged down by them.

Some of the humour had been created by the contrasting conditions which the author found himself in, especially in the early years after Pakistan was created. It appeared that he left civil service to join the banking sector on the advice of Mr Isphahani who wanted qualified personnel to run the finances of this new country, as there was great shortage of them in the field. As Yousufi had himself described, the social attitudes of the Muslims of the subcontinent were averse to this sector. It was totally dominated by the Hindus while the Muslims lived life to the hilt without ever thinking about the sources that were needed to sustain such a lifestyle. He joined the banking sector and gradually rose to the very top.

Then there was the constant drone, his sidekick Mirza Abdul Wadood Baig, who had a take on everything -- characters, social mores and the peculiarities of our society. His take verged on the absurd and so far over the edge that it seemed preposterous and unrealistic, but the contrast that it offered was sufficient to spread a smile on the face of the reader.

One characteristic of Yousufi had been that though he had focused much on the character types that are thrown up by our culture and society; he treated them not with contempt but with sympathy and humour. In other words, there was little scope for treating those characters as caricatures as they retain their fuller personal traits and at the same time one knows why they have become so. In humour, there is always a vantage point. For Yousufi this vantage point was downplayed to the extent that it did not seem to exist frontally and in your face. But at the same time the cutting edge of humour was retained. It could probably be that he was looking at general human foibles and traits that were there and one was not able to overcome and were pulled down by them. In this very sympathetic consideration, comedy brushes closely with tragedy.