Gyan Chand Jain has built a convincing case that language should be freed from its heavy political baggage and seen independently as language

The question of language has been so mired in political controversy that it cannot be seen in an objective light away from the various prejudices that have embroiled it. The situation has aggravated because of the nationalist struggle in which one of the defining points was also the question of language. Urdu was seen as the language of the Muslims while Hindi was promoted as the language of the Hindus.

Gyan Chand Jain has built the case that language should be freed from its heavy political baggage and seen independently as language by linguists and philologists, and not be swept away by the forces that have robbed it of its objectivity. For Jain, Urdu and Hindi are not two but one language and their antecedents lie in the various dialects that were spoken in the area they originated from. The most prominent or the generic was the Khari Boli Hindi and it comprised other dialects like Haryani, Brij, Awadi, Bhojpuri etc.

He is of the view that language or the basic structure of the language does not change. The point of view that Urdu is an amalgamation of languages, especially those that influenced the local ones from outside like Persian and Arabic, is therefore flawed because it can add to the vocabulary and increase the stock of words and phrases but does not alter in any significant way the structure and the character of the language. Similarly, the script also does not change the nature of the language. The fact that Urdu and Hindi have different scripts does not really mean that the languages are different in a fundamental way.

The scripts can be different but the language remains the same as testified by the change of script of many languages. The Persian language script was changed by the conquering Arabs in the 7th century but it did not result in Persian becoming another language or least of all Arabic. It remained as Persian.

According to Amrit Rai, the beginnings of Hindi can be traced to the 12th century while Ramchandra Shukla started his quest from the ‘Vir Gatha Kaal’ comprising 12 books from the 8th century but Rai dismissed 10 books and cast doubts about the 11th as well.

Urduwallahs may trace their origins in the poetry of Amir Khusro or in the Bigat Kahani, in the 13th century and then take it from there to the Bahimi Kingdom in the Deccan where Urdu as we got to know the language in later phase was instituted at a more formal level. But to trace with any degree of consistency to the 19th century and then the 20th when the controversy actually spread like wildfire and gained currency is very difficult to establish. Jain does not disagree that Urdu is a hybrid of languages and after the patronage of Muslims, it blossomed at a later date.

Urdu too has had its detractors and has fought for its legitimacy. For centuries there was a debate about the two schools of Delhi and Lucknow and in tow there was Hyderabad, but when the Punjabis began expressing themselves in Urdu it resulted in a divisive furore. Iqbal’s diction and use of Urdu was run down on an industrial scale and jokes were crafted out of it. This derision had a lot to do with the regional or class bias as reflected in the language than the nature or evolution of language itself. The common front for one language against another probably took shape at the time of partition.

It should not be forgotten that Urdu language only belonged to the ashraaf [elite] in both the cities; the common people did not speak the language. Only a small upper class spoke it and many from the mazafaat [suburbs] spoke one dialect at home and another more formal in societal forums. But with partition and migration, everything changed.

When Josh visited Lucknow from Pakistan in the mid-1960s, he was horrified against his own firmly held belief of the changes in the famed city and the insistent use of the slang.

The question is who is to decide that language and its criteria? Previously it was the court. In the 20th century, Urdu was a crafted idiom that was hardly spoken by the common man belonging to the various regions in Britain.

Given the political controversy weaved around the issue of language, it becomes increasingly clear as one goes through the pages of the book that it is impossible to separate the chaff from grain. Politics is so deeply ingrained and the scholarship so imbued with it that separation begins to look like a political act.

One thing is particularly clear that the issue has generated immense heat from either side of the battle lines. There are so many polemics involved that it is difficult to keep scholarship and politics away from each other. Reactions are so extreme that it either makes scholars diffident and circumscribed or to use a polite phrase ‘very cautious’ because the political backlash can be venomous; never a good condition for dispassionate scholarship to thrive in.

The book nevertheless gives a good account not only of the issue involved but the environment in which it is being debated. The heated environment is probably the best outcome that one can be exposed to and this itself is a statement that does not require further explanation.

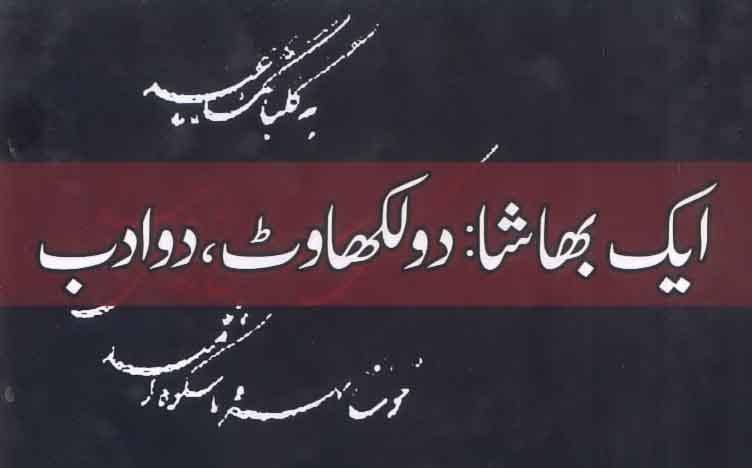

Aik Bhasha, Do Likhawat, Do Adab Author: Gyan Chand Jain

Publisher: Fiction House

Pages: 311

Price: Rs500