Even though it did not get the Man Booker Prize, this bleak Arab tale will be cherished for the virtual tour de force it really is, truly a world-class masterpiece

This Arabic novel by a relatively lesser known Iraqi writer recently shot into world attention when it was nominated for the Man Booker International Prize 2018 and tipped as a hot favourite. It had already won the International prize for Arabic Fiction, which is to the Arab world what the Booker is for Anglophone circles. To no one’s surprise, it caught the world’s attention. Pakistani author Ghazi Salahuddin mentioned it in one of his articles, but we are dependent upon English translations for any substantive introduction to world literature.

Favourable reviews of the recently published English translation caught my attention and I started following the news, ready to take a bet on it. The evening of the prize announcement had me nervous and expectant. My mind kept reverting to the well-lit venue of the ceremony at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the occasion when Intizar Husain was nominated in 2013 and I was privileged to attend the ceremony.

My sense of disappointment was repeated in full force as I heard the prize being announced for another title. I knew next to nothing about this winning title, and therefore was in no position to draw a comparison between the two. I was concerned about the novel I was left holding in my hand. I would rather comment on it because of its own intrinsic qualities and not as the novel that did not receive the Man Booker.

I remember a similar situation in Urdu when Mumtaz Mufti’s voluminous Alipur Ka Aili gained notoriety as "the novel which did not get the Adamjee Prize", and even more ironical is that the novel that did won the prize, Jamila Hashmi’s Talash-e-Baharan, is even less known. So the tag of shortlisting will soon fade away, I am sure, and this novel will be cherished for the virtual tour de force it really is, truly a world-class masterpiece.

More than the prize, what is gripping is the link to the original novel Frankenstein, which is memorable and appropriate at this moment. The happenings of a dark, spooky night have passed into the lore of literature and how the twentyish Mary Shelley participated in a session of telling scary, ghost stories along with Byron and Shelley, two of the most powerful among the English Romantics.

The novel Shelley wrote is an undisputed classic, a precursor of modern science-fiction with its dystopic vision. As a young boy I had breezed through the novel making nothing more than a spirited and thrilling tale of adventure. It was a coincidence that I finally read it again now in the year of its bi-centenary. In its second reading I encountered a disturbing book of Prometheus gone wrong, thoroughly contemporary in its concerns over the limitations of science.

The moral vision and the appearance of the monstrous creature in the classic English novel gets a fresh lease of life in this bleak Arab tale. Taking the mechanical apparatus of fashioning an almost human figure, this novel’s setting is a powerful depiction of Baghdad, a city being torn apart in a senseless frenzy of destruction. The name links the two novels with each other but the Arabic novel intensifies its irony by not moving too close with the English original. Frankenstein becomes a local phenomenon, one that is a product of its milieu.

It opens with a document-style Final Report on the "activities of the Tracking and Pursuit Department," immediately contextualising the war-torn Iraq with its crumbling civic infrastructure and the US military intelligence. None of these elements are overbearing, they are only placed in the first sentence so that you cannot forget. The report concludes by recommending that the personal information about the author is incorrect and that he should be re-arrested and questioned again. The author’s details will materialise in the course of the novel but the report places an ironical frame around the purpose of which is to become apparent later.

The focus of the novel’s action is "the Frankenstein’s monster", as he should be properly called, resurrected and reconstructed in modern day Baghdad, no longer the city of Arabian Nights but still a city of improbable tales. A cast of ordinary citizens is living in a crumbling neighbourhood, and soon we encounter Hadi. He is a storyteller but known as a liar, and in one of his incredulous stories he speaks of carrying a large nose in a sack, collected from a fresh corpse because it was the last bit required to complete a human being made up entirely of the body parts of people who have died in bomb explosions on the streets. This creature comes to be known as ‘Whatsitsname’ and ultimately this is the name law enforcing agencies will use when they want to blame all crimes on this mysterious person. Shades of the na-maloom afraad can be felt; Baghdad could be Karachi as statues of Virgin Mary are beheaded and terror walks the streets.

While the police are ready to blame him, Whatsitsname explains that he is really the only justice in the country. Old parts would fall off as he completed his vengeance by killing off the people responsible for the explosion but he needed new flesh from new victims. He goes on to claim that he is "the model citizen", made up of people from diverse background achieving an integration which had never been achieved in the past.

Journalists, tv anchors and investigators become embroiled in rapidly unfolding action as the monster can no longer remain a secret. We are told by a character that he "assimilates the wisdom that transcends the bounds of wisdom and that, without knowing it, he speaks with the tongue of pure truth." The same could be said about this grim and remarkable novel. Cleverly structured and artfully narrated, it is a grim reminder of a war-torn and ravaged reality which cannot promise to be Promethean. The only real monster is the war which reduces people to a rubble of body-parts and is fed on revenge of the innocents.

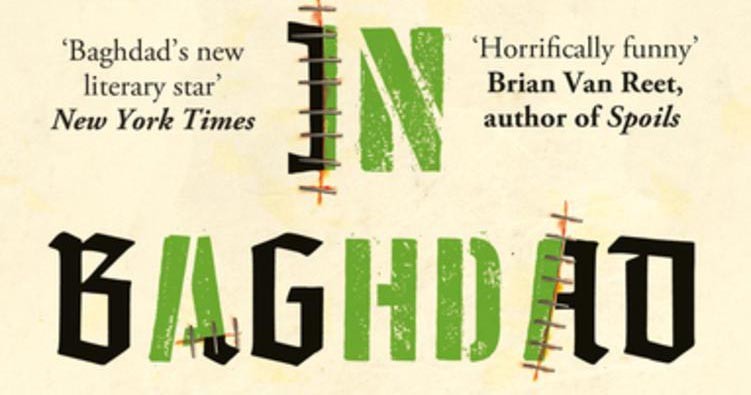

Frankenstein in Baghdad Author: Ahmed Saadawi

Translator: Jonathan Wright

Publisher: Oneworld

Pages: 288

Price: Rs1,165