Pakistan is a haven for pirated books, international and local. One reason for this is that too many books are difficult to find, and when available, are too expensive

In the 6th Century AD when St Columba made an illegal copy of St. Jerome’s Psalter, by hand, he was caught and a judgement was passed against him by King Diarmait of Ireland. "To every cow her calf," reasoned the king in this early copyright case, "and to every book its son-book. Therefore, the copy you made, O Colum Cille [Columba], belongs to Finnian."

It has been 1,500 years since but even today piracy is flourishing. Readers have moved from manuscripts to e-books but the pirates have kept up, they now make pirated e-books as well, despite the numerous piracy laws in place.

Pakistan is a haven for pirated books, international and local. One reason for this is that too many books are difficult to find and, when available, are too expensive. Another cause behind the piracy is that Pakistan does not host many branches of foreign publishing houses. The country only houses one international publishing house, Oxford University Press.

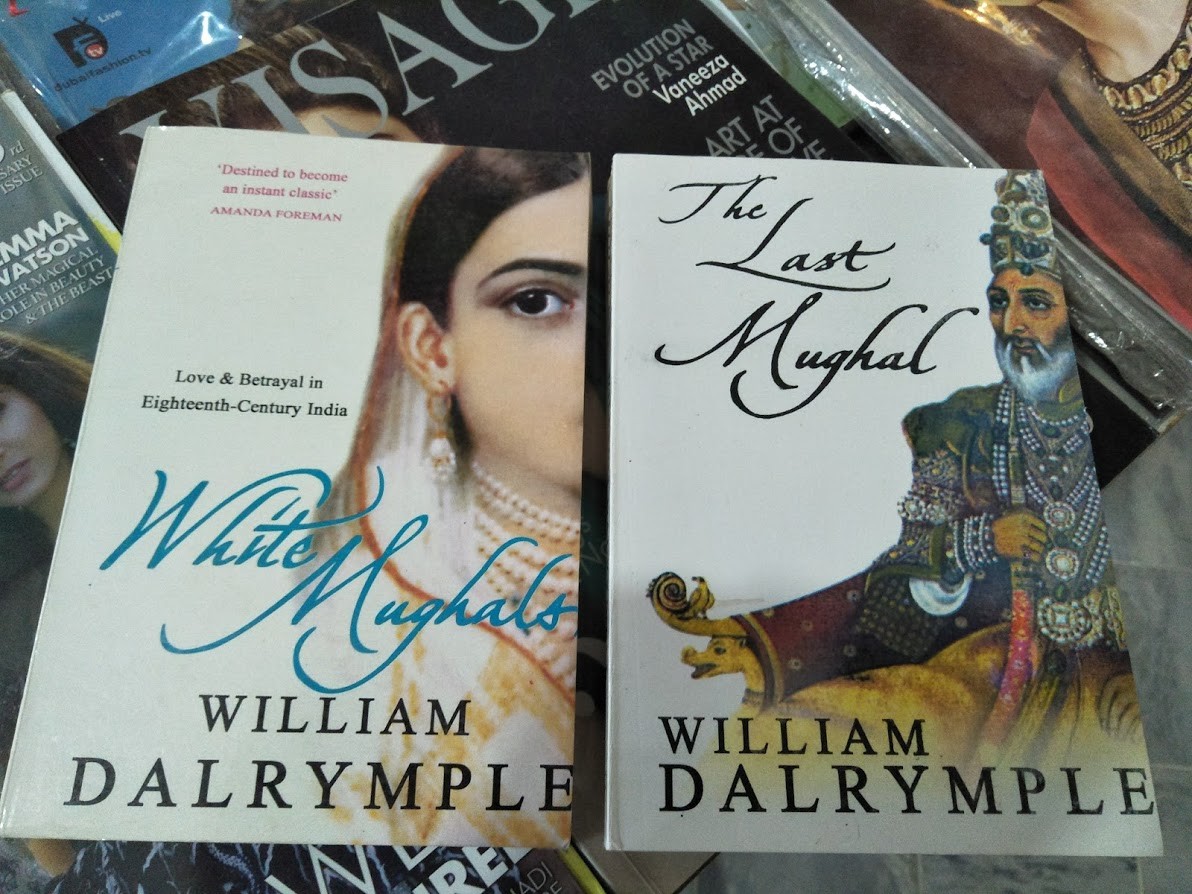

In local markets, you can easily spot pirated books ranging from English Literature to Management Sciences to International bestsellers and even dictionaries, at low prices. Pirates, sometimes, release copies of books in local bookstores before the original is released.

One group that relies on pirated books comprises students. Already bogged down by heavy fees, neither the students nor parents can afford expensive original books. Not educated about copyright laws, often the students are not even aware that using pirated books is a crime.

Pirated books of fiction, non-fiction and course work variety are easy to find across the country, the big unanswered question is how they are distributed to booksellers and how the business network runs?

Walk into a bookstore in Lahore, Karachi or Rawalpindi, and inquire the price of a certain book, the sellers will quote two prices, one for the legitimate version and one for the pirated. Ask them where these illegal copies were published and they will say they purchased these books by their weight and didn’t ask who published them.

One such bookshop owner in Rawalpindi, Mumtaz*, says "We have pirated editions of almost all international bestselling titles. After the original book is launched, within weeks we receive the pirated copy. Most of these editions are supplied from Karachi. The reason we sell pirated books is because it allows us higher profits". He adds it is the "customers who demand the pirated editions, because their foremost concern is price".

This despite the fact that Mumtaz has dealt with copyright issues closely. His bookstore houses various pirated books, however there is one local publisher from whom Mumtaz only buys original. "In 1997, a publisher filed a case against my elder brother and me, for selling pirated O’ and A’ Level syllabus books. We were released on bail, but today you will only see original copies of that publisher’s book in my store."

Tin Bazaar in Rawalpindi is a hub of pirated books. Similarly, in Lahore, you can find pirated books in Old Anarkali’s Sunday Bazaar, and in Karachi Urdu Bazaar is the place to go. The major beneficiaries of piracy are publishers who manufacture pirated books and booksellers. Some pirate private publishers have improved their modus operandi by using high quality paper -- this makes it difficult for buyers and readers to know if the book they have purchased is pirated or original.

A unique case of piracy in Pakistan is what we saw with the second edition of Juma Khan Sufi’s autobiography, Faraib-e-Natamam. His publisher made pirated copies of his book, and Sufi reported the case to the Federal Investigation Agency’s copyright wing. The publishing house was raided by the authorities and eventually the publisher was arrested and later bailed out. The court case still lingers on. "The hearings are moving at a snail’s pace," says Sufi.

Pakistan signed the intellectual property rights protocol on April 8, 2005. An autonomous body, titled the Intellectual Property Organisation of Pakistan (IPO-Pakistan) was also established under the administrative control of the Cabinet Division. This law requires countries to set minimum standards for the protection of intellectual property.

On July 25, 2016, the administrative control of IPO-Pakistan was transferred from the Cabinet Division to the Commerce Division. The major functions of the body include administering and coordinating government systems for the protection and strengthening of Intellectual Property (IP); Manage all IP offices in the country; Create awareness about IP Rights; Advise Federal Government on IP Policy; Ensure effective enforcement of IP rights through designated IPR Enforcement Agencies such as the police, FIA, and Pakistan Customs.

However, there are two problems with this set of laws, firstly it was not implemented effectively and hardly anyone is ever punished. Secondly, the minimum punishment is too low. The penalty under the current law, the Copyright Ordinance, 1962, is up to three years of imprisonment or a fine of Rs100,000. This fine is doubled for second or subsequent offences.

One explanation for why laws are so weak in Pakistan is because there is no research or evidence to prove piracy. Is a crime still a crime if no one takes it into account?

While it is easy to understand that people cannot afford costly books, we must also recognise that by purchasing pirated books, we are violating the rights of writers and publishers. The affected are the writers.

"Our nation can spend millions on food and weddings, but refuses to spend even a few hundred on books," says Ramsha Ashraf, an academic and poet. She believes that this is a cause that the writer community should collectively take up. "Writers need to intimate the society about the exploitation they face at the hands of pirated publishing strategies," says Ashraf.

She says that to cope with book piracy we have to provide books at subsidised prices and for this, government departments like the National Book Foundation (NBF) need to play an active role.

NBF established in 1972 is currently headed by Dr Inamul Haq Javed. He agrees that "NBF was established to promote availability of books at moderate prices. We are working to promote reading habits and cheap books."

Dr Javed says that since he took charge in 2014, more than 200 new titles have been included to NBF’s book list. But he also sees the need for more work. "Piracy in Pakistan is good for students because sometimes they cannot afford books and need photocopies. But another solution to this problem can be that we establish more public libraries with updated catalogues."

Pirated books are even sold online on social media forums. There is need to spread awareness about copyrights laws as it is a big threat to creativity.

*Name has been changed to

protect anonymity.

The writer is a journalist and traveller who collects rare books.