Ten years after his death, everybody seems to have forgotten Shahbaz Malik, an artist who challenged notions of "good art" and established concepts

Dead painters do not produce any work, so how to write on them? Not many private galleries show their pieces, nor do we have public art museums and galleries in which works borrowed from private collectors can be exhibited. At the National Art Gallery Islamabad or Alhamra Art Museum Lahore, the works are displayed in a certain order. Rarely do we have curated exhibitions that lend a chance to view an artist in a different way. The change of context may also add new content to it.

Thus, artists when they die leave the realm of art as well. Unless their children are in the same profession or galleries profit from their work, they are denied a place in the history of art.

I realised this when I recently spotted two canvases of Shahbaz Malik at an art gallery in Lahore. Malik graduated in Fine Art from the National College of Arts in 1986. A passionate and prolific painter, he didn’t have a settled life and secure job; thus remained an outsider. Although he moved between Lahore and Bahawalpur, he continued to paint and held regular exhibitions at galleries such as Canvas, Chawkandi, Nomad, Croweaters, Shakir Ali Museum, Rohtas 1, A.N. Gallery, V.M. Gallery, Alliance Francaise and others. He sold works and yet was not a commercial success. He kept working, experimenting in different mediums, techniques and imagery.

Almost ten years ago, in December 2008, his family and friends got the devastating news of his death. The loss became bigger when his work disappeared from public memory. You don’t often hear about him in art discourse and occasionally see his canvases in someone’s house. No book on Pakistani art mentions him (although books too cannot ensure a lasting life), nor is his work available at galleries for resale.

A few friends and colleagues can recall him, but many don’t know there was an artist called Shahbaz Malik. This is ironic because when I saw his paintings hanging in the corridor of the gallery, I was shocked by the power of those images. Although I was familiar with his work (Shahbaz was a close friend and class fellow at NCA), still those surfaces surprised me by their ‘newness’.

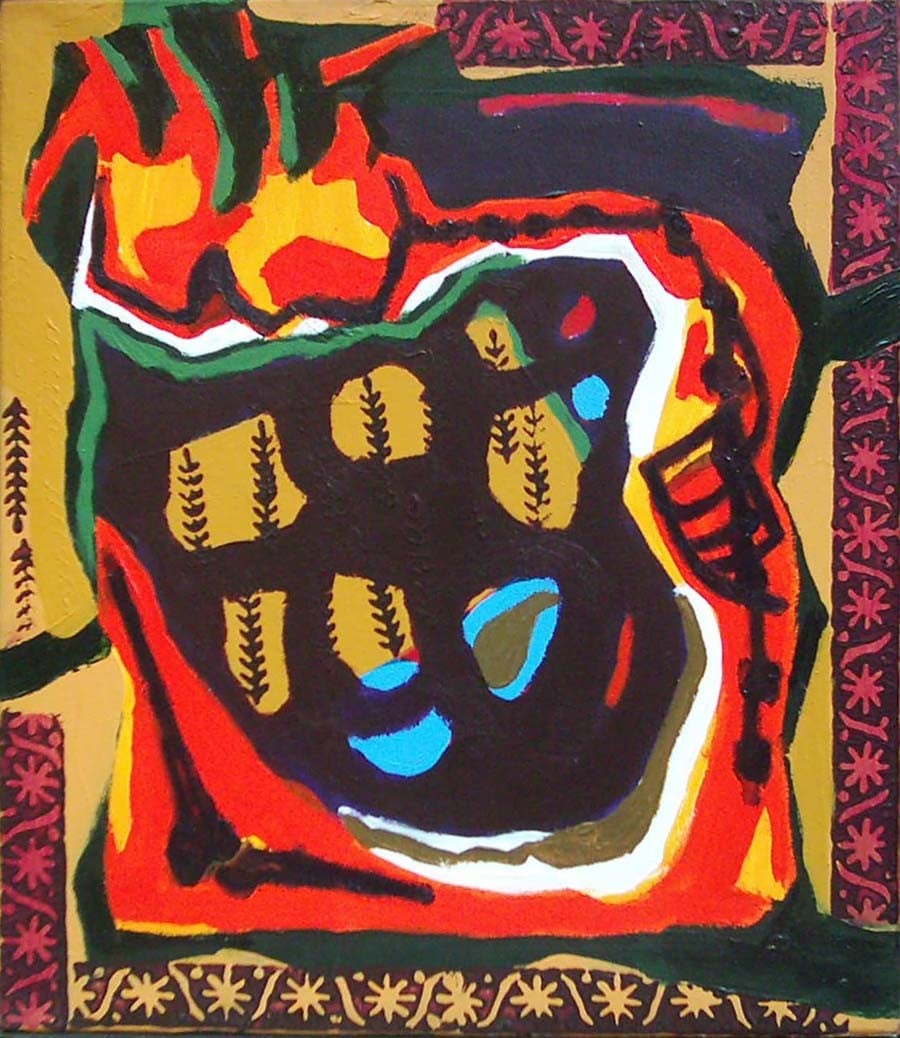

Transformation of human figure and its background into stylised language with its connection to folk patterns (block printing of Southern Punjab) is just one angle to read the visuals. When you see them now, you are baffled by the use of colour -- untamed, and unmatched. Some aesthetes were not comfortable with his colour palette, but Malik courageously continued with that chromatic order that appeared raw, uneven to a sensibility conditioned by subtle shades, harmony and pictorial balance. These concerns look redundant today; the works of art have to annihilate established concepts of taste in order to introduce new ones.

Shahbaz Malik’s art did manage to do that; only nobody realised it at the time. His work was bought by a number of important collectors due to its unusualness, but it was hardly perceived as mainstream. The artists persistently pursued his vision, without much recognition or acceptance. Perhaps, he was not even aware of his achievement; he was more concerned about painting the way he could, as artists tend to.

A span of ten years -- of silence -- is sufficient for viewing his art with a new eye. A work remains the same, only the audience changes; hence the different readings of Kafka. When I look at the paintings of Shahbaz Malik, I feel the artist challenged norms of ‘good art’ much like Jean-Michel Basquiat’s canvases which defy existing aesthetics but have a power that cannot be denied. The combination of hues in Malik’s canvases is a sign of his painterly genius, because no one was able to follow (copy?) or come closer to it. The unique pictorial sensibility was not wild but refined: with layers of paint on top of each other till the artist achieved what he sought.

What was it that he sought? Recognition, money, fame, comfort? Perhaps all of that but not in huge amounts. He struggled, strived and spent his savings in a career that did not have huge returns. His individuality was the driving force behind those canvases wherever he lived, in Lahore or in his hometown Bahawalpur. His uncommon sensibility makes his work worthy of a second look and for a due place in the hierarchy of Pakistani art.

I suspect it won’t happen because Shahbaz Malik didn’t teach, nor did he have an offspring to push his work and re-launch it into the local and international art market. So the paintings would remain unnoticed, obscure, behind the door of a house, in a corner of a living room -- like their creator who was a bit of a recluse.

In that he wasn’t much different from another painter of high ranking, Mansur Salim, who passed away in 2015. Salim was an extraordinary figure in the art of Pakistan but not many people remember him. An artist who in the early 1980s was making installations, doing performances and creating works of mixed media of an uncanny nature. Those works are etched in the mind of a young student that I was at the time but, sadly, not in the popular narrative of Pakistani art. Dedication to work and no connections with the major manipulators of the art world led to his solitude and low visibility. After his death, one hardly hears about him or sees his extraordinary canvases.

In contrast to these two artists, there are several others who are showing frequently, have been written about, collected, admired and respected, whereas their works are merely a series of repetitions, borrowed from other sources, decorative and sentimental stuff.

We need to search for these two and also for numerous others who may have been brilliant artists but are lost not because of their death but due to their distance from the power and centre of art world. This distance that can be covered, only to discover geniuses in our surroundings, unsung and unhung.