As the country’s ‘first transgender school’ or a vocational institute opens in Lahore, it draws attention to the larger issue of virtually no educational opportunities for them

Khushbu, 25, knows all the answers in class, before anyone else. Sometimes she remembers to raise her hand before answering, but other times she forgets the class rules and blurts the answer out too fast. When this happens, she is gently reprimanded by the substitute teacher.

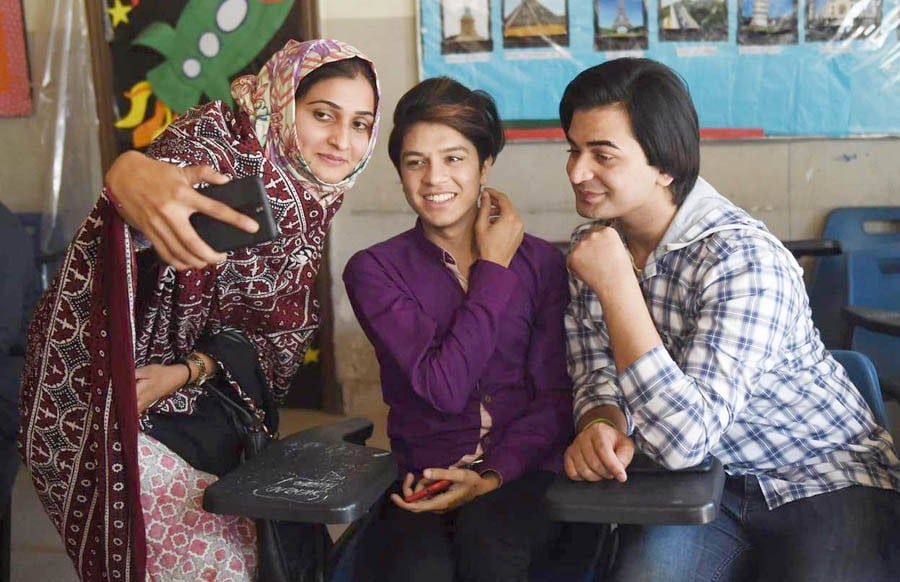

The Spoken English teacher couldn’t make it to work that day, so the Event Manager of Exploring Future Foundation, the non-governmental organisation (NGO) that runs The Gender Guardian, the institute that claims to be ‘Pakistan’s first transgender school’, stepped in and taught the class. There’s also a shortage of board markers, two classes are sharing one. But the lack of the marker doesn’t stop Khushbu, Sheela, Mohammad Sarwar and three others from excitedly studying. They say there’s a thrill about being in a classroom that’s indescribable.

"After I had to leave school in the fifth grade because of personal reasons, I never imagined I’d have a chance to be back," says Mohammad Sarwar, about 40, who runs a tea stall at Ameer Chowk in Lahore’s Township area. He’s here to learn Spoken English and cooking. "Cooking classes haven’t yet begun, but the school is only about a month old," he says. "It’ll pick up soon".

Others have similar motivations to join the school located in Lahore’s Model Town. Khushbu, a food operator at a private university in Lahore, heard about The Gender Guardian through her guru and comes there to study Spoken English, and learn the skills of cooking and make-up. Make-up is a hot favourite course and if you opt for it you also get a full supply of basic beauty items. "Many transgender people aren’t good at make-up, and it’s such an important skill for us, we need it for our occupations and daily life, so we all want to learn it well," says Mohammad Sarwar.

The students, most of whom are between 25-45 years old, also rave about a class they had on law, last week. A lecturer, whose name they don’t remember, taught them about their legal rights. The students are still moved by the class. "It made us realise the way the police interact with us is completely illegal. The lawyer taught us how to respond to policemen, and made us feel empowered," says Sheela, a transgender female student at the school.

But these growing pains, of missing teachers and markers, is not the central issue surrounding the school. Currently, the institution’s identity lies in being ‘Pakistan’s first transgender school’ -- this is in line with a hot trend of ‘firsts’ in Pakistan’s transgender community which recently saw the country’s ‘first transgender model’ and ‘first transgender news anchor’.

The traditional understanding of a ‘school’ is that it runs through weekdays, for about 5 hours a day, and provides structural learning of Urdu, English, Math, Science and so on. Given the state of Pakistan’s syllabus and education system, you could see this as a blessing or a curse, but The Gender Guardian is not a ‘school’ in the traditional understanding of the word. It is a vocational centre, or an academy that runs, according to founder Asif Shahzad, on Saturdays and Sundays for three hours, and according to some of the students, only on Sundays.

Shahzad himself has told the media: "Most of them [the students] have shown interest in sectors of the fashion industry including learning about cosmetics, fashion designing, embroidery, and stitching while some have also shown interest in graphic designing and culinary skills," thereby implying that the institute’s main function will be to provide vocational training to transgender persons. And while setting up a vocational centre for any gender or sexual minorities in the country, is a commendable achievement, Shahzad has ruffled many feathers by claiming that the institute is more than it is.

In response to these allegations, Shahzad says, "We have made the option of schooling available. If transgender people want to come and study the syllabus from nursery to matric, we are capable and ready to teach them." But none have come forward for that yet. Khushbu is ready to take her Matric exams, and the institute’s staff is truly supportive of her endeavours, but she’s been studying for those exams for years while the institute only began earlier this year.

Shahzad isn’t affected by these accusations, he is focused on his goals which he claims is empowering the lives of the transgender community by supporting their education and finding them gainful employment. The institute is currently in talks with a ride-sharing app, his hope is they would employ Shahzad’s "good looking, educated" graduates as drivers. The added burden of having to be ‘good looking’ along with ‘educated’ in order to be employed is perhaps forced on all genders that aren’t strictly male.

It is easy to criticise Shahzad for his problematic attempt at educating and mainstreaming transgender people. What is more difficult is figuring out if this style or form of education is not going to work then what is? Learning how to read and write in Urdu and English should be a basic right, but is currently a privilege only accorded to those born in particular classes and genders. Shahzad’s institute is trying to change that, so should we not give credit where it’s due?

Neeli Rana, a transgender activist and a coordinator at the Khawaja Sira Society, a Lahore-based rights organisation, doesn’t think so. "They are robbing people in our name," she says. Her concern is that if the school wanted to bring about constructive change, why didn’t it work from the ground up and build something inclusive? "Why didn’t Shahzad do his research and ask the community what they wanted?" she asks. She remembers that a few years ago Naz Health Alliance received a grant from the World Bank to support transgender education and the first thing they did was come to the community, learn their needs and create a syllabus that was aimed specifically at the community. "The project may not have lasted long, but we loved learning there while it did. Instead of talking at us, that coursework spoke to us," she says.

Rana has always felt that her illiteracy has held her back. As an activist she constantly needs to text and email people and always having to ask someone to do that for her slows her down. "The community needs education. Many transgender children drop out because of bullying, harassment and sexual violence in schools. Others drop out because they don’t have a support system at home to send them to school, or they have to earn money during school hours," says Rana.

According to Mehlab Jameel, a transgender rights activist who has studied in semi-government, government and private institutions to complete her secondary, intermediate and undergraduate education, the harassment can begin as early as in grade 5. That’s when children are roughly 10-years-old.

"In all-boys’ schools, the least masculine boy is chosen and then harassed and bullied year after year," she says. As the children grow older, the harassment worsens. In the all-boys’ government college in a small town in Southern Punjab, where Jameel is from, students who do not fit into gender norms, particularly those suspected of being transgender were tormented with threats of abduction, rape and video recordings and blackmail.

The point is, how can students who don’t fit into society’s gender binaries study in an environment that is actively hostile? It’s difficult to learn your multiplication tables when you also have to devise how you will fight three teenagers rubbing themselves off you when the teacher leaves class. Should we then focus on more institutes like The Gender Guardian that separate transgender people and place them in safer environments?

Jameel doesn’t think so. She thinks such initiatives are ‘saviour’ projects and act only as band-aid solutions. "Without undermining the relief such projects can provide, I want to point out that they derail the important conversation about reforming the education system," says Jameel. Others suggest that co-educational schools, training teachers to cope with such situations, and having more transgender teachers, may be a solution. Still others, such as Uzma Yaqoob of the Forum for Dignity Initiatives (FDI), an Islamabad-based transgender rights NGO, says that instead of such exclusion, we need a more inclusive syllabus. "Children need to be taught about people outside the gender binary at a young age and that will help them be more tolerant towards each other," she says.

Shahzad’s response to this is that if girls and boys can have separate schools, then why can’t transgender people? "After all we live in a Muslim society," he says.

Needless to say, there is much work to be done for transgender education. One vocational centre for transgender people isn’t going to end the community’s problems of systemic injustice and inequality that they face on a daily basis that includes riding in gender-segregated public transport, police harassment, and lack of employment opportunities to name just a few. Nor is the centre claiming to end all problems.

It is simply a starting point where a handful of transgender people can learn English, cooking, driving and make-up skills and feel safe for a few hours a week. Some community members feel satisfied with this, while others are confident this funding could’ve been used in a much better way if the community was consulted and included beforehand.