Ghazal was owned by the establishment of the new state as the foremost musical expression of Pakistan, and Mehdi Hasan came to be known as its greatest proponent. Today, the ghazal is almost extinct

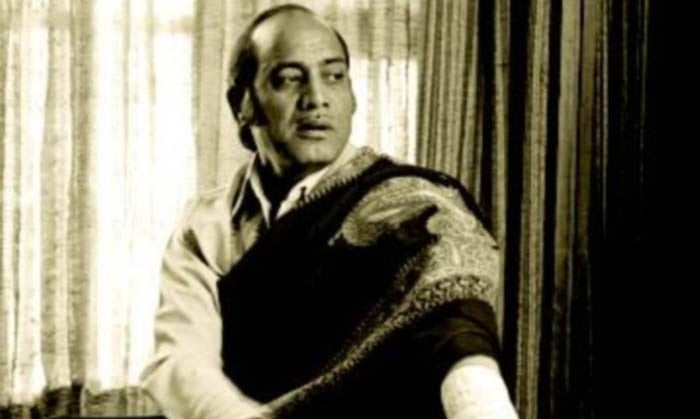

It can be said with certainty that some of the vocalists who died in the last twenty odd years have not been replaced. Though no artiste who passes away from nature to eternity is substitutable but at least there are others who keep the flame of high standard of music alight with their brilliance. But very few have been left today and none has taken the place of Mehdi Hasan, particularly in ghazal gaiki. Trained in the dhrupad khyal tradition being a gharanedaar vocalist, Mehdi Hasan switched to singing initially the thumri and then the ghazal for which there were more takers in this part of the world. The forms like khyal were listened to less and less and vocalists like Mehdi Hasan voluntarily or driven by the force of their talent started to infuse the simpler ghazal gaiki with the virtuosity of the khyal and thumri.

It became clear very early on that greatness was about to coronate its new king. And as the 1950s turned into the 1960s the flow of new songs was incessant. It was not only the quantity but the quality that was amazing and made the connoisseurs of music sit up and take notice. But not much has been achieved since he passed away in 2011. Actually, the ghazal with its solid basis in the traditional ang of gaiki has been in decline. Probably Abida Parveen is the only top of the line vocalist who is still singing the ghazal with full conviction along with her trademark rendition of kaafi, particularly the Sindhi kaafi, but otherwise from among the younger generation it is difficult to pinpoint and identify any outstanding prospect. Shagirds, mainly Ghulam Abbas and Asif Javed had been performing on various occasions over the years in programmes to keep his memory alive, but unfortunately one of his most cherished shagird Pervez Mehdi died some years ago at a relatively young age.

Under the changing musical environment and the ingress of technology, particularly the computer-generated sound, the way the note is intoned has changed drastically. This has transformed the total ambience against which music was received in our traditional culture. Keeping within the tonal matrix of our music Mehdi Hasan actually developed a completely new style of singing. Since he was from Rajisthan he brought with him the ang of the very rich tradition of the Jaipur gaiki. By integrating the maand-a folk form he created an ang which was rendered with a constricted throat that went along wonderfully well with the recording and microphone devices, as the very fine and subtle nuances were captured.

In music forms where the lyrics play an important part the greatest challenge for the vocalist is to break through the limitation of meaning that the grid of word imposes. The significance of the sur has to dominate and take over. In the classical forms in the Indian subcontinent lyrics were kept to the minimum and subordinated to the tonal pattern of melodic formations. These were usually expressed through the combinations and permutations of any particular raag or even a subtle mixing of two or more raags in various tempos.

This has to be further distinguished from recitation or cantillation which in various cultures, including our own, have had an equally old and venerated tradition. The recitation, or cantillation, or what is generally known as tarannum is only a musical illustration of the lyrics and its virtue too is supposed to rest there. But the moment it liberates itself from the limitation of the word to assume a definitive tonal form it is supposed to be assessed from a musical point of view rather than a fumble about finding a relationship between the note and the word.

Mehdi Hasan’s father Azeem Khan and uncle Ismail Khan were court singers and he was trained by them but the most definitive influence was that of his elder brother Pandit Ghulam Qadir. Mehdi Hasan capitalized on his rigorous training as a khyal and thumri gaik and by paying due importance to the lyrics struck the right balance between the melodic and poetic content. As a ghazal singer he shot to fame in the sixties with Gullon main rung bhare and as his genius was spotted went on to sing in rapid succession a number of ghazals that have now become classics of the genre. He sang Mir, Ghalib, Faiz and Faraz with great sensitivity but at the same time a number of other poets, not that well known, who are now popularly recognised because of his rendition. But he remained very careful in selecting the kalaams of good poets and not necessarily popular poets, many of whom made a name for themselves as film lyricists.

The imperatives of identity helped in promoting the ghazal in the new state of Pakistan for it was premised that the ghazal represented a cultural continuum that was closer to the Muslim identity. In poetry, since ghazal had grown from the interaction between the Persian and local traditions, and since most of the practitioners were Muslims, it was owned by the establishment of the new state as the foremost musical expression of Pakistan. Ghazal was patronised and it basked in its appeal to the middle class urban audience. In the later phase qawwali took over to assuage the contradictions that rued many in the decades ruled by the display of piety.

Ironically both ghazal and qawwali were considered minor forms in the centuries of Muslim rule in the subcontinent. Dhrupad and khyal reigned supreme, while ghazal was restricted to the salons, and qawwali to the shrines.