One needs to trace why there is no space left for visual arts in Urdu writing

‘In showbiz circles, news of intimacy between stage actor Afreen Pari and a boy dancer is being spread. Artistes associated with theatre mention that Afreen Pari has fallen in love with a dancer called Waheed; both have made commitment to each other. However, Afreen Pari denies all these rumours.’

This ‘valuable’ information was provided by an Urdu daily some weeks ago on its culture page along with a few more stories like this about performing artistes’ lives, loves, and luck. As it is, finding writings on Art is a rare phenomenon in the Urdu press. Whatever little you found mostly revolves around gossip.

Same is true for journals and magazines published in Urdu. Occasionally, there is reportage of an art show, review of an exhibition or interview of a painter. Often, in those sparse texts, unknown individuals are projected, there’s preference for flowery language, while a critical or analytical voice is absent.

This was not always the case. In the past, particularly in the 1960s and 70s, one came across writings on art by literati such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz on Chughtai, Quratulain Hyder (Art ki Kahani); and Muhammad Hasan Askari, Muzaffar Ali Syed, Dr Enver Sajjad, Dr M. D. Taseer, and Intizar Husain writing on individual artists, and on general issues of art and culture. A number of practising painters, A. R. Chughtai, Shakir Ali, Hanif Ramay, Sadequain and A. R. Nagori also contributed texts on art in Urdu.

There is a visible void when it comes to serious or original Urdu art writing today. One hears constant laments and heartache on dominance of English in the local art discourse, and almost a complete disappearance of our regional languages (Punjabi, Pushto, Balochi, Hindko, Siraiki, Brahawi - except Sindhi) from the field of writing on art.

If one recollects the early texts on art, one recognises there was a greater interaction between literature and art. Artists used to read literature (some even wrote fiction like A. J. Shemza, Raheel Akber Javed and Tassadaq Sohail). Likewise, writers used to frequent art exhibitions and wrote on art and artists. Perhaps, it was in response that Ozzir Zuby made sculptures of some writers.

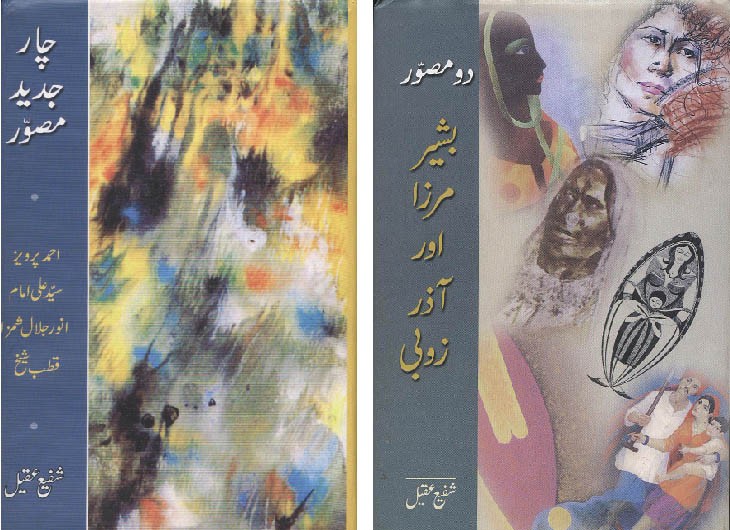

There were debates and discussions in Lahore’s cafes about new art and new literature. Urdu literary magazines such as Sawera and Funoon allocated a section on art (if excavated from public and private libraries, these could be gathered into a magnificent collection of Urdu art criticism). A personal relationship between artists and Shafi Aqeel is manifested in the finest example of art writing in Urdu.

That period of our cultural past seems to have vanished. It appears as if once the artists started to sell their work on comparatively better rates, they drifted away from literature. While artists moved up the social ladder, fiction writers remained those typical romantic characters struggling for bread and butter. Works of art were purchased, utilised for decorating a house and considered an investment. On the other hand, any work of Urdu poetry or prose may perhaps be great in merit but was without any monetary worth. There occurred a disconnect between these two forms of creative expression.

With the international acceptance and popularity of English literature from Pakistan recently -- providing money, fame and prestige to authors --a relationship between contemporary English fiction writers and artists has emerged. There are crucial and serious factors to understand this newly formed association.

The gap between visual artists and Urdu writers was also caused due to lack of communication. Artists rarely read Urdu literature, although they may be familiar with names such as Ashfaq Ahmed, Bano Qudsia, Munir Niazi, along with Ghalib, Iqbal, Manto and Faiz. Similarly, Urdu writers are not acquainted with the vocabulary of contemporary art. When they visit a gallery, or look at the works reproduced in a catalogue or book, they are unable to decipher it, let alone write about it.

The diction of contemporary art is an international idiom, understood or guessed by a public, trained, fluent or frequented in it. It hardly matters if one spots an installation at some gallery in Guatemala, Germany or Japan; one does not require a ‘translator’ because the concerns, mediums, techniques are shared by many practitioners across the world. Although each artist deals with the local context and specific situation but a viewer from another region/culture is still able to comprehend the content.

This is exactly the situation with our contemporary writing in English. Books such as Moth Smoke, Our Lady of Alice Bhatti, and Other Rooms, Other Wonders are connected to reality of this land, yet are understood in most parts of the English-speaking world.

Due to its language, construction and concerns, there is an immense exposure to contemporary art of Pakistan in the world. Regardless of whether they speak Urdu or a regional language, artists in their work converse in an international idiom. Understood here (though not by a greater population; a situation parallel to English writing, accessed, but not by a large community), and at the same instance lingua franca of centres of mainstream art.

Only if the language of contemporary art changes or we adapt to it, there may be a shift in the scenario of art discourse in Pakistan, and we will start writing in Urdu. Otherwise, there will be superficial and patronising exercises, of naming exhibitions in Urdu, or attempts in literal and lifeless translations -- both of text and ideas.

However, there have been a few brilliant examples in translating important art books, including Herbert Read’s The Meaning of Art by Shahnawaz Zaidi; Salima Hashmi’s The Eye Still Seeks by Julien Columeau (forthcoming); Marjorie Husain’s Aspects of Art by Shahabuddin Shahab (a text book for colleges and universities); and a few chapters of Salima Hashmi’s Unveiling the Visible by Shoaib Hashmi. One hopes that with more translations, we will be able to revive original Urdu art writing, and may approach our art and criticism through a different lens. Translations not only make available an actual text, these add a new flavour to language and offer a new angle to the initial text; reminding one of British orientalist Arthur Waley who preferred to read Dickens in Chinese translation!