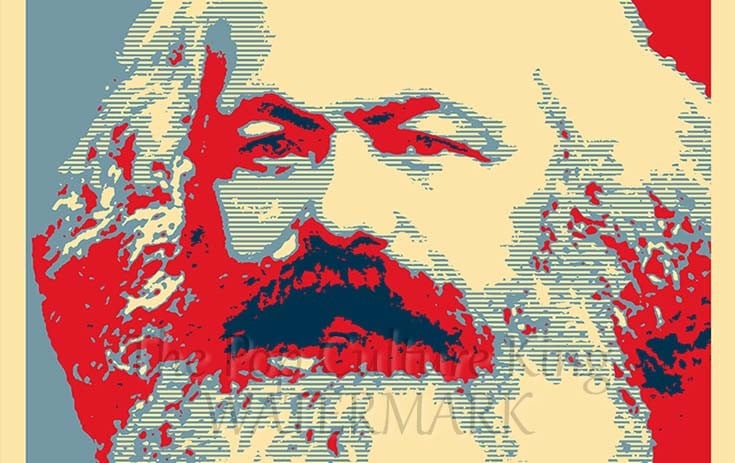

The damage done to the academia milieu by disallowing a critical engagement with Marx

Karl Marx’ bicentenary did not go unnoticed even in Pakistan where his ideas and theories exist as aberration to the nationalist narrative that is interlaced with religious ideology.

Reading Marx critically was no less than a heresy for many people back in 1978-79. So much so that when Ziaul Haq’s Islamisation campaign was set in motion, some zealots from various departments of the Punjab University took out books on Marxism and torched them to ashes.

This was revealed to me by Prof. Qamar Abbas, a veteran academic and activist, who served at the Punjab University for almost four decades. Such an act was deemed necessary by the ‘neo-Islamists’ to wipe out the atheistic influence from the land of the pure.

Neo-Islamists were those who found their identity in religion only after Ziaul Haq assumed power and legitimised his rule by playing up the Islamic card. Prior to the Operation Fair Play in 1977, they held ‘the middle of the axis’ position; they were neither to the left nor to the right of the centre. Later they joined the ranks of the religious right.

This unequivocal adherence to the ideology became the measure of academic excellence. Thereafter, Marx and his ideas were banished from academic spaces. Academics teaching Marxism were demonised and some of them were hounded out of universities.

What was the damage done to the academic milieu of the country by disallowing scholars to have critical engagement with the most influential thinker of the modern era? "No thinker in the 19th and 20th centuries had perhaps so direct, deliberate and powerful influence on the world as Karl Marx. The strength of his influence was unique. He completed the bulk of his work between 1844 and 1883, a period of democratic nationalism, trade unionism and revolution. Neither Marx’s mind nor his pen ever stopped moving".

It seems pertinent to reflect on ‘Historical Materialism’ to put my view in perspective.

It is the condition of material life of society that determines the physiognomy of society, its ideas, views, institutions etc. But the question is, what are these conditions of the material life of society? Of course, the nature or geographical environment is an indispensable condition of the material life of society and influences the development of society. But its influence is not the determining influence. Changes in society occur at a much faster rate than changes in the nature.

Similarly, the density of population plays an important role because without a minimum number of people there can be no material life of society. But again this is not the determining role because a higher density of population does not necessarily produce a higher social system. The chief determining force, according to Historical Materialism, is the methods of procuring the means of livelihood or the modes of production of material values such as food, clothing, house, etc. The instruments of production and the people who operate them jointly constitute the productive forces of society.

Despite the influence of his ideas in the 20th century, Marx’s personal influence and ideology were time-space bound. But his ideas had ubiquitous appeal and the impact they cast was profound and long lasting. Obviously, he was critiqued and rightfully so.

Two most important points of criticism are: it rules out the influence of two many other factors and it reduces men to a "horde of will-less automatons"; and, it is a fatalistic theory opposed to the doctrine of free will of overlooking the importance of human agency. Yet another important limitation of Marxist thought is that it does not take into account "revealed knowledge" which in the course of human history is known to have brought about significant changes.

The work of great artists, poets, dramatists and men of similar type cannot be accounted for by this theory. If economic forces dominate society, how do different aspects of social life form an organic whole, as Marx asserted.

In my view, it would have been better if Marxism was critiqued in a constructive manner instead of being dismissed without having any interface with it. The utter disregard shown to Marxist thought did a colossal damage to the disciplines of social sciences as well as of humanities. I have seen with agony, Pakistani academics’ insouciance as some of them cover the entire Marx in a single lecture, a true retribution that Marx is being subjected to for being a non-believer.

In a postcolonial society like Pakistan, the social realities and dichotomous relationships which create and construct those realities, could hardly be scrutinised without drawing on Marxism. After the demise of Hamza Alavi and Aijaz Ahmad having moved to India, Pakistan does not have any academic with good theoretical grounding in Marxism.

Thus, the instruction offered in the disciplines of social sciences is starkly devoid of any theoretical or conceptual underpinning.

I advocate that the process of indigenisation of knowledge will take place only if we engage with theory. In order to master ‘theory’, Pakistani academia will have to become involved in Marxist ideas and debates that emanated out of these ideas particularly from 1968 onwards.

Read also: Marxism and the end of history

Marx was variously interpreted over the span of 125 years. Isaiah Berlin’s biography of Marx is quite instructive and offers critical insights for the students of political theory in particular. More so, from Antonio Gramsci to Althusser and from Horkheimer and Theodore Adorno to Jurgan Habermas and Slavoj Zizek, Marxian thought appeared in various shades. Far from being static, it changed with changing times. Even in the extenuating circumstances as these, quite a few commentaries and exegetical analysis of Marx’s text(s) can be found in libraries. But any meaningful debate or critique on Marxism is sparse in our universities.

Importantly, postcolonial theory came about, to a great extent, in response to Marxist formulations. Ruefully we are still stuck with classical texts in the courses of English literature, being offered in most of the institutions of higher learning. Now when internationally postcolonial theory seems to have passed its prime, and some consider it has become a bit redundant, we are still conjuring up excuses to prevaricate its introduction in literature courses.

--To be continued.