In Jamil Naqsh’s recent exhibition at Tanzara Gallery, the delight is more in treating the surface than the subject matter

It is mere coincidence that Jamil’s Naqsh’s solo exhibition that travelled to Lahore from Islamabad organised by Tanzara Gallery was held at the Nishat Hotel (May 5-6, 2018). Nishat in Urdu means pleasure, which is an important ingredient of Jamil Naqsh’s art: the enjoyment in treating the surface and delight of the subject matter.

Arthur C. Danto observes "one cannot look at the painting of a naked person simply as a painting". So the works on display invite readings beyond formal. The exhibition includes three points in Naqsh’s forte -- nude females, birds, and women holding them. For years, Naqsh has been painting ‘nude’ instead of a ‘naked’ body. Kenneth Clark makes a distinction between the two: "To be naked is to be deprived of our clothes and the word implies some of the embarrassment which most of us feel in that condition. The word nude, on the other hand, carries, in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone."

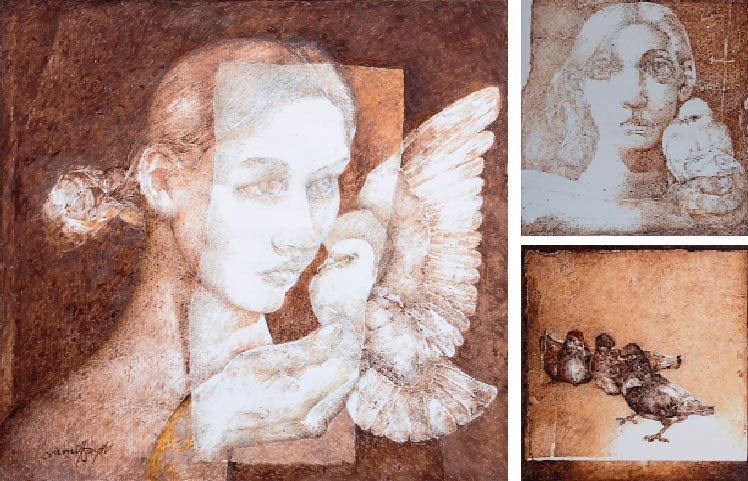

Naqsh’s canvases depict models who, in most cases, are not aware of the presence of an onlooker. Instead, they are engaged in their world (the artist’s studio!) where they turn, twist, sit, bend, recline, lean, lie, hold a bird in their hands, or are surrounded by one or more pigeons. The artist seems delighted not in seeing his models but in translating human flesh into a flesh of paint. Applied with brush or knife or both, the surface becomes the supreme obsession of the painter who manipulates his marks, textures and tones like a master weaver.

Like in the past, this time too one observes how the painter has built the form of a face, hands, breasts, body through interwoven brush lines. Compared to several other artists who dealt with nude in their paintings (Colin David for example), the canvases of Naqsh are not smooth. Instead, he transforms the body into a web of paint, spread unevenly, especially in this show.

There are numerous paintings by Naqsh in private collections (such as ‘A Tribute to Shakir Ali’ 1976, at the Shakir Ali Museum) where a woman is not a body but an accumulation of varying patches and hues. Naqsh drapes his nudes in layers of brushwork, so what we encounter first is not an unclothed figure but a painting. The smoothness of skin is substituted with rough texture of paint, almost covering it in a coarse cloth.

Our eyes do not comfortably catch the contours of a woman, but stop, stumble and shift, while discovering the detail of the body. Even though the subject can be classified as provocative, erotic or sensuous, one must recognise that it is the painter who has looked at the body in its natural state, and what the viewer sees is the version of Naqsh. Actually, that version is more about the painter than his model. When combined with birds or paintings of pigeons only, the viewer discovers that the artist is pursuing purity -- of a human body without clothes and of a bird with its feathers.

Both are connected on various levels. One connection can be traced in the brief art history of Pakistan: Shakir Ali’s painting of nude woman with a parrot (1969), or different works portraying human figures and flying birds; or in the Indian miniature paintings in which a princess is holding a bird. The last one reminds of the famous exchange between Emperor Jahangir and Empress Nurjehan. He left a pair of precious pigeons with Nurjehan but on his return discovered that one was missing. When he inquired how one pigeon flew away, the queen released the second pigeon from her hand, illustrating how it had happened.

In Naqsh’s paintings, the birds are mainly held in the hands of women who seem to be offering them to the viewer but, through the handling of paint and colour scheme, there is link between human body and the form of bird. Both appear to become one. Not exactly subscribing to the Christian iconography of The Virgin Mary and Dove, one does see some sort of spirituality in the depiction of the two entities. Or a sense of innocence, the common thread between a young girl and a pigeon.

But all these readings can be superfluous. These indicate the usual habit to locate meaning -- rather inject narrative -- in images. In reference to Naqsh’s art, one realises it is more about the sensitivity of surface than the sacredness or severity of subject. More than the charm of naked body, the transcription of it is more important for the painter. He does not follow his gaze and projects body as a voluptuous living entity (like Lucien Freud or Jenny Saville) but a flat image on a flat canvas.

Small but significant decisions such as slicing and separating figure into different quadrangles or in grid suggest that what we see is not a nude woman but a shape derived from that source, and transformed. Modification occurs through stylising form, elongating neck, geometrising features, exaggerating contours and selecting the same hue for human figure, bird and background. In some paintings, a couple of pigeons are simplified to such an extent that they appear like mechanical figurines -- recalling Cubist imagery.

In the catalogue of the exhibition A Homage to Ethereal Beauty, one reads that the painter, in 1953, "studied Indian miniature painting with the late Ustad Mohammad Sharif". The paintings in the current show were mostly made in 2017 but, even after 60 or more years, one can still recognise traces of miniature painting in them. Using small brush strokes for developing features can be associated with the technique of pardakht from miniature painting. Likewise, introducing an edge at the side of his imagery indicates the existence of a paper, an illusion reinforced by the torn line that divides the compositions in most of his works.

Birds do become old and die but, in our perception, they are ageless in the sense that one replaces the other; hence the specie remains unchanged. The female figures next to pigeons as represented in Naqsh’s work also seem beyond the bound of age; like birds, they are timeless. What we see in them is not the passing of years that leave a mark on skin or in features, but the purity of an idea based on the pleasure of being -- a reflection of Jamil Naqsh and his nishat, his art.