Pakistani citizens have no legal recourse available against data breaches by social media giants. What can the citizens then do?

We live at a time when digital technology is not only an intrinsic part of our everyday lives, but its own advancement is at an accelerated rate. With that rapid growth, however, comes greater abuse of the information that we feed into devices and digital network platforms. Consider for a moment the data you create and share online: what would this entail? Your browsing history; call logs, messages of all kinds on all media; statuses shared on your profile, sent and unsent messages in your Facebook Messenger; deleted personal comments and everything else that you have done or shared online -- all of this is your property. Just as you would insure and protect priceless jewellery or family heirlooms because of their value, your data carries value, and must be protected just as strongly.

Multibillion dollar corporations such as Facebook and Google have built their fortunes upon business models that are heavily reliant on the monetisation of user data to third parties in order to generate profits. These companies, contrary to public statements, have been found to siphoning more data than what they have told their users and government regulators.

Facebook recently found itself in hot water once again, this time for letting a UK-based data analytics firm, Cambridge Analytica, harvest data of nearly 100 million Facebook users through a 60 question survey that aimed to collect psychoanalytical information of users. What people were not aware of, however, is that the online survey did not just collect the data of those that had voluntarily consented to the terms of the questionnaire, but also of their friends that knew nothing about the survey. It was then used by Donald Trump’s presidential election campaign during the US elections held in 2016 and was also used for the Leave EU campaign during and leading up to the 2016 UK referendum to leave the European Union. In each case, the parties that utilised Cambridge Analytica services were successful.

This does not just reflect on the weak data protection policies that Facebook possess but also is evident of the breach of trust that it keeps demanding from people. An average internet user comes on Facebook to scroll through their timeline without having to worry about where their fingers stop to react to a post and those finger taps being recorded to disrupt democratic processes in a country that is seen as an example to most of the world.

In 2017, Google was sued by a UK-based consumer rights campaigner, Richard Lloyd, on the ground that the company had allegedly worked to bypass Apple’s default privacy features in order to eavesdrop on 5.4 million iPhone users and collect their online behaviour using Safari, which was then used to target ads through Google’s DoubleClick advertising business. Tracking the browsing habits of users online and offline -- what activists and critics would call "Surveillance Capitalism" -- in order to tailor ads and thus increase revenue is how Google builds its empire.

"Data is the new oil", a statement that has been highly criticised, nonetheless resonates with people, as it provides an analogy that highlights the importance of data to these tech giants. A sense of resignation and weak legislation work together to give Google, Facebook and Twitter a monopoly, and lets them dictate in essence what happens to your data. In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal that costed Facebook somewhere close to $100 billion, a campaign to delete Facebook gained momentum. While deleting Facebook is a matter of privilege, what it will eventually do is distance users from their own data that will still be stored on Facebook’s servers for other data analytics companies to harvest at any given time.

As Mark Zuckerberg said in a recent interview with Vox Media, in "a lot of ways Facebook is more like a government than a traditional company" -- even while frequently promoting the concept of Facebook as community rather than commodity.

The problem of weak data protection, however, isn’t restricted to social media websites and search engines. In fact, more concentrated platforms like dating or fitness apps are equally invasive. For example, dating apps like Tinder hold a huge amount of information on its users. Because it requires the person to login using their Facebook account, the cross-connection of platforms multiplies the data of the user on several servers. This data could potentially be sold to advertisers, and in more dire consequences, can be hacked and leaked to be used against you. Grindr, another dating app, was to be found leaking sensitive user information, for example, including their HIV status, and their personal location -- via geolocation -- which was reportedly being used in turn to allow people to track them down and cause them physical harm because of their sexual orientation.

What can go wrong?

Search for your own name via Google search, and you may come across a host of webpages about or on you that you were unaware of. A political opponent or stalker could use your own political stances or public messages against you. The murder of the university student Mashal Khan serves as a particularly horrific example of this -- material was posted about Khan online that was false, but what was uploaded caused several of his fellow students to kill him.

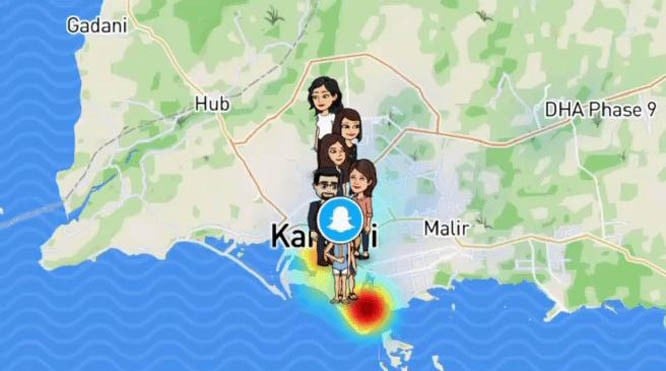

Geolocation is one of the features in modern technology that has been abused to perpetuate violence without any repercussion. Snapchat which happens to be one of the most famous smartphone applications among young people has projected a new feature that allows people to see where their friends are at any given moment based on their geolocation through a built-in map called Snapmap. This map’s accuracy is hard to question and so are the risks associated with it.

Next in line are location tracking apps such as the Punjab Government’s Women Safety App -- ironically introduced to protect women from street harassment -- launched in 2017. In addition to the lack of proper respect for privacy with the lazy copying and pasting of privacy policies from US-based websites, these sort of applications have the potential to be misused against women who come from abusive households and may suffer from increased societal surveillance. There have been instances of women being forced to install location-tracking apps on their phones by their families or partners without their consent, and forced to share their live location -- the latter being a feature that WhatsApp has also recently introduced. Deviating from their usual commute could end up costing a woman her life or worse.

Pakistan has suffered its share of mass data breaches by foreign actors, state and non-state. In 2011, the US-based National Security Agency (NSA) and UK-based Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) were found tapping into the identification records of Pakistani voters saved with the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA). By the face of it, the incident may not seem to constitute damage but what happened here is not a matter of whether someone got hurt. Instead, it is the fact that identification documents of the citizens of Pakistan were in the possession of foreign government agencies without their knowledge and consent. The government of Pakistan is responsible for protecting the information of its citizens at all costs, and this theft of NADRA database is a breach of trust that the democratic governments around the world require from their people.

However, it transpires that the NADRA database has been compromised multiple times at different instances. Digital Rights Foundation researched on the number of times the national database was breached, visual representation of which can be found here [PDF].

What can the citizens do?

A good first step to reassert citizens’ control over their personal data is to ensure that they are fully informed of the ubiquitous mega trends in the storing, processing and sharing of their data and are rightfully consulted.

Freedom of information is the right to "request" access to data and enquire about its use, including the alacrity with which the relevant authorities address these requests -- especially if they pertain to personal information. This fundamental right is extended to the right to "informational self-determination" and requires "prior" knowledge of the individual, of what information is or might be stored.

This right is narrowly reflected in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) -- adopted by the European Union -- which will come into force on May 25, 2018. It will completely change how public information is used by companies, governments and other entities. It confers new rights on people to access the information companies hold about them, obligations for better data management for businesses and a new regime of fines.

It will most significantly reshape the internet by changing the data protection landscape affecting other parts of the world. It sets a higher bar for obtaining personal data than seen previously, explicitly extending to companies outside the EU. It requires companies to obtain explicit and informed consent from users and lets them request a copy of their personal information. Under GDPR, a single violation could also potentially cost companies 4 per cent of their global turnover.

Pakistani citizens, however, have no legal recourse available -- unlike Europeans -- against data breaches by social media giants due to the lax monitoring of third-party data access and the lack of law and policy on data-sharing within private companies.

It is believed that in order to reassert the citizens’ right to privacy, it is imperative that the government gives more control to the people who supply data rather than the social media companies. They should also encourage transparency and develop trustworthy mechanisms to hold private companies including foreign entities to account and call for international cooperation in discouraging practices that violate privacy.

Digital Rights Foundation has brought the need for data protection legislation to the national forefront. We recently disseminated a policy brief to all relevant ministries hoping that the government would review the legislation on data collection by public and private entities.

The onus of protecting user data doesn’t only fall on social media companies but also on the government, rather more on the latter than former -- to formulate better policies that grant security to citizens and their data in online spaces.