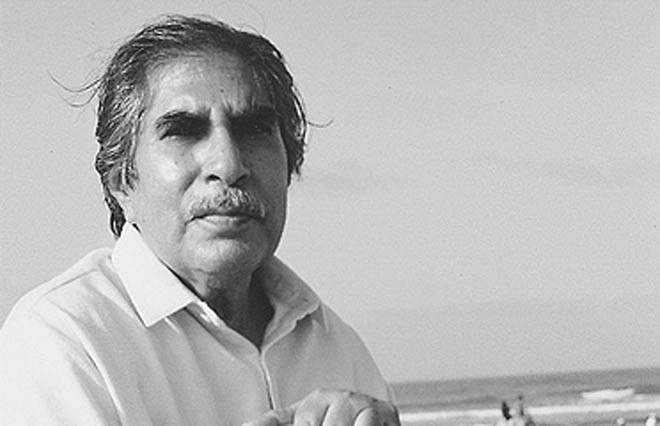

Remembering the politics and poetry of Shaikh Ayaz and the great legacy he has left behind

Shaikh Ayaz needs no introduction. The most well-recognised Sindhi language poet, his greatest gift lay in ghazal. But he expressed himself in all genres of poetry. Ayaz’s translation of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s poetry in Urdu provided Urdu speakers with an opportunity of reading Bhittai. Ayaz brought about innovations in bait, waee and other classical genres of poetry.

Born on March 23, 1923 in Shikarpur, he received his education up to intermediate in his hometown. Later he did his B.A and LLB from Karachi where he started practising law in 1950.

Ayaz began writing at a young age. He started with verses on Sindhi nationalism and Marxism, then moved to poetry about God and his benedictions, and even tried his hand at naats. Ayaz’s first nazm was published in a magazine in 1933.

He entered into the world of literature formally in 1946 when he wrote short stories that appeared in a popular magazine. Ayaz started writing poetry under the guidance of Kheyal Das and continued writing from 1947 to 1997, only taking a short break after partition when many of his Hindu friends migrated from Sindh.

At the start, Ayaz wrote poetry signing it off as Mubarak Ali Shaikh, his real name. He even published Agta Qadam, a small magazine in Sindhi. But due to partition and the migration of many Sindhi Hindus to India, the magazine shut down after just three issues.

Partition saddened him but soon he mingled with Urdu speaking migrants and began writing poetry in Urdu. His collection of Urdu poetry was brought out in 1954. Ayaz was well-versed in English, Sindhi, Urdu, Persian, Arabic and Punjabi.

His first book of Sindhi poetry Ja Kaak Kakria Kapree was published in 1962 by the Writers Guild which was banned by the government of West Pakistan for promoting Sindhi nationalism. His second book of poetry Bhanwar Bhara Aakas was published in 1963 and was also subsequently banned for the same reason as the first.

In 1958, he arranged and presided over an All Pakistan Literary Conference in Sukkur. This conference was a watershed moment that proved his time had come. One of Ayaz’s unique qualities was his exhaustive knowledge of azad nazm, prose, kaafi, nazm, ghazal, geet, kato, chou sitto, and hiko. He utilised all these genres in his work. Ayaz used simple words and painted poetry with new and different Sindhi words.

After partition, Ayaz returned to Sukkur and started visiting villages where he would observe customs, traditions, daily life, culture, language and dialects that he wrote about later in his poetry. During the movement against One Unit, Ayaz composed poetry that that supported the restoration of Sindh as a single province. Rasul Bux Palejo and Ghulam Muhammad always defended Ayaz and praised him in newspapers and magazines.

Ayaz also avidly read foreign literature. His father Shaikh Ghulam Hussain, who was also a lawyer, purchased books for Ayaz, inculcating in him a reading habit. His favourite poet was Khayam whom he had memorised; other poets that he liked were Rumi, Keats and Shelley.

Ayaz has 63 books to his credit, of which 39 are collections of poetry in Sindhi. Fourteen of his books remain unpublished. Ayaz’s books have been translated in Urdu, English, Siraiki, German, Greek and Russian.

Ayaz was not a communist but ideas of communism were present in his poetry. Ayaz’s poetry depicts the sufferings of the oppressed people of the world: he wrote about humanity, the famished and starving people of Ethiopia, the victims of Nagasaki and Hiroshima and the suppressed survivors in Vietnam. He also highlighted the miserable state of the Tharri people who bear starvation during droughts. He wrote about how they are forced to leave their homes in search of food and water. He also raised his voice for poor labourers and haaris.

Ayaz desired to do a PhD on the Persian poetry of Allama Iqbal but he could not -- due to his busy schedule and the five heart attacks he suffered. His weak heart was also what turned him towards God and religion. Once, while in the hospital for heart treatment, he was declared dead for a few minutes. Later, Ayaz said he saw his soul being taken speedily through a tunnel where abruptly he was stopped and his carriers were asked to take him back to the world of the living. He found himself on the hospital bed. His family members were surprised to see him alive.

After this, he started reading Nahj-al Balagha and composed his religious poetry. He declared that God had given him an opportunity to return to the right track. He stopped smoking, only occasionally bringing unlit cigarettes to his lips to beat his habits.

When Ayaz was the editor of Daily Barsat, he wrote about his favourite writers and poets from around the world every day. In his personal library, it is rumoured that he owned 100,000 books. All these books were burnt when rioters attacked his house in Sukkur during ethnic riots in the 90s. He then established a new library in his house in Karachi. It is said that despite the library, his room and bed were so scattered with books that there would be little space on his bed for sleeping.

When Z.A. Bhutto and Ayaz were put in prison by General Ayub Khan, Bhutto promised him to make him Vice Chancellor of Sindh University Jamshoro. Later, Bhutto fulfilled that promise and Shaikh Ayaz became the VC of the university on January 23, 1976. But he was removed from this post in 1980, and that was when he again started his law practice.

During his tenure as VC, Ayaz tried to improve education in the university; he appointed many talented people like Abdul Qadir Junejo, A.R. Nagori, and Sahar Imdad.

In 1988, after his heart problem developed, he moved to Karachi and continued practicing law and holding literary get-togethers to satisfy his poetic thirst.

His verses still echo in the minds and hearts of his fans and poetry lovers and nobody can forget his sermons, speeches, fictions, editorials that have carved out a special niche in Sindhi literature. He received Sitara-i-Imtiaz for his literary works and is regarded as a "revolutionary and romantic poet".

Ayaz passed away, ultimately from a cardiac arrest, on December 28, 1997 and was laid to rest near the Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Mazaar. A mazaar has been erected for Ayaz, under the instructions of former chief minister Sindh Arbab Rahim. Money was also allotted for the publication of his remaining work.

Literary figures have demanded to name the Shikarpur Library after Shaikh Ayaz. They have also asked that his house in Shikarpur be given heritage status, and that his remaining works be published as soon as possible. They have also requested that a signboard be installed at the main gate outside Ayaz’s mazaar.

Some time ago, there was a complaint about the open, unsheltered grave of Shaikh Ayaz. Sattar Pirzado, a dear friend of Ayaz, responded in poetry saying Ayaz had refused to have a roof on his grave. Such was the man.