The funerals of 17 Kashmiri youth have become a security concern for the establishment which reacted by curtailing the internet and imposing curfew-like- restrictions in many parts of Kashmir

As many as 13 militants, four civilians and three army personnel were killed in clashes in southern Kashmir on Sunday, April 1. This has been the worst spate of violence the region has seen this year; the clashes were spread across different villages including Dialgam, Dragad and Kachdoora.

Reportedly, security forces received intelligence about the presence of militants in Dragad in Shopian district as well as other villages. But when clashes between militants and the police began on April 1, protestors poured onto the streets, chanting slogans against Indian occupation and pelting stones at the forces - the idea was to create a distraction and protect the trapped militants.

The troops used tear gas and pellet guns to diffuse the crowds, and later opened fire. Many of the protestors sustained pellet wounds and at least six were wounded with bullets, says the police. Others report that at least 150 people were injured during these clashes.

The civilians who were killed and injured during the encounters gave more wind to the protests in southern Kashmir until they spread across the province. "The death of civilians along with homebound HeM and LeT militants began a terrible wave of violence and has signalled the arrival of another bloody summer in Kashmir," a local from south Kashmir told The News on Sunday.

The next day, on April 2, Srinagar-based newspapers ran ‘Mayhem in Kashmir’ and ‘Bloody Sunday’ as banner headlines.

This joint operation to take out militants in the Shopian and Anantnag districts was termed as a ‘Special Day’ by the police who have told Indian newspapers that the process will help bring peace in the Valley. However, most districts of Kashmir remained shut for the next three days.

The ‘Special Day’ was followed by strikes and calls of "Shopian Chalo" to express solidarity with families who lost loved ones during Sunday’s clashes - the strikes were organised under the joint leadership of Tehreek-e-Hurriyat’s Mohammad Ashraf Sahrai, Hurriyat Conference’s Mirwaiz Umer Farooq, and Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front’s Yasin Malik.

One civilian, 22-year-old Gowhar Ahmad Rather of the Kangan area, who was shot in the head on April 1, succumbed to his wounds the next day in Srinagar’s SKIMS hospital triggering further protests.

According to S.P. Vaid, the director general of police in India-held Kashmir, most of identified militants were youths driven by the idea of violence. "We tried to facilitate a meeting before the Dialgam encounter by taking the militant’s parents to him. They spoke for almost 30 minutes to convince him to surrender, but it heeded no results … and finally the army had to take action against the militants," says Vaid to reporters.

There has been an increase in educated young people joining the ranks of militants. Last year almost 124 youth joined militant ranks in Kashmir compared to 88 recruits in 2016 and 66 recruits in 2015.

According to the police, in the first three months of 2018 alone, more than 25 young people have already joined armed groups, this number also includes the son of Tehreek-e-Hurriyat’s Chairperson, Junaid Sahrai, a 28-year-old MBA graduate from Kashmir University and Mannan Wani, a 25-year-old PhD scholar from Aligarh Muslim University.

Another identified militant who was killed in the Draggad encounter on April 1 has been identified as 23-year-old Zubair Ahmad Turray. His funeral prayer was led by his father and according to Kashmir Life, "One of Turray’s friends offered his funeral prayers, donned in a combat dress and exhibiting his gun publicly".

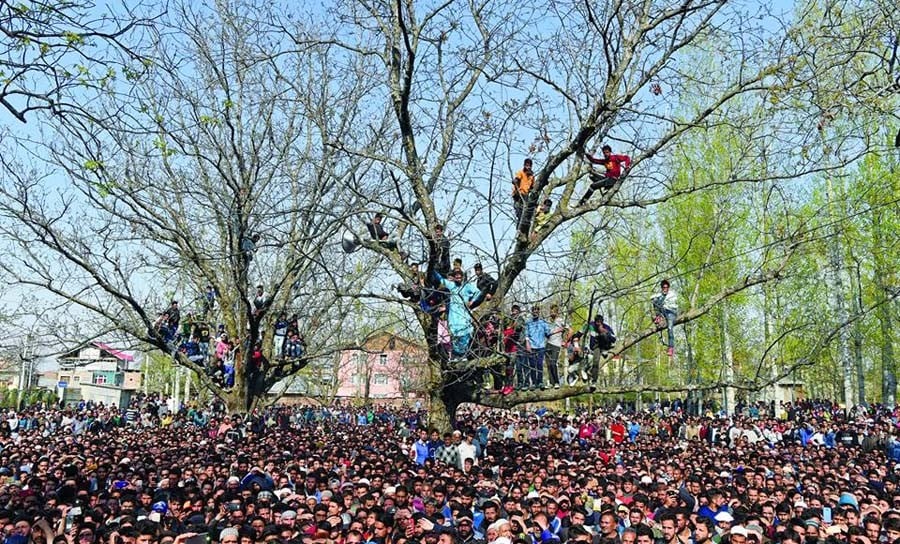

The funerals of the 17 Kashmiri youth have become a security concern for the establishment which reacted by curtailing the internet and imposing curfew-like-restrictions in many parts of Kashmir, including Srinagar’s downtown. However, despite the restrictions, tens of thousands of people joined the funerals of the fallen militants and civilians.

The state apparatus has previously maintained that "the massive gatherings at funerals of killed local militants post the 2016 unrest is a serious concern that has to be addressed … These gatherings romanticise and glamourise the militants and boost militancy," says one intelligence report published in The Indian Express. "The funerals of killed militants have become a fertile ground for recruiters," reads another report that was dispatched to Vaid in February.

The phenomenon of attending funerals in high numbers began in the early 1990s, ever since armed rebellion against Indian rule broke out. Before this armed struggle, people would only gather in large numbers at rare occasions; one example of this was when Sheikh Abdullah, the leader of the National Conference, died in 1982. "The gathering at his funeral stretched for many kilometres," says a witness.

Almost nine years later on May 21, 1990, another massive crowd gathered outside SKIMS hospital to take the body of slain Mirwaiz Farooq who was killed by two gunmen at his residence. While his funeral was en route, it was intercepted by paramilitary forces at Srinagar’s Hawal area and was ‘indiscriminately’ fired upon. Fifty-six civilians died that day and dozens were injured.

In 1991 after Ashfaq Majeed, a member of the HAJY group, was killed in Srinagar downtown, a huge crowd gathered at the shaheed malguzaar [martyrs’ graveyard] in Iddgah.

More recently, in October 2015, when Indian forces killed Abu Qasim, the oldest-active militant operating from south Kashmir, a sea of people attended his funeral leaving the state confused. The confusion came from the fact that although Qasim was a Pakistan-origin Lashkar-e-Taiba militant fighter, villagers of Pulwama were fighting each other to claim his body.

The support base for militants took a radical shift with the emergence of the 22-year-old charismatic Burhan Wani. His funeral prayers were held in absentia, across both borders, by lakhs of people for over a week.

Attending a funeral holds religious connotations, but in Kashmir attending a funeral of martyrs, especially those of rebel-fighters, also holds a sense of belongingness and solidarity towards the cause. Each time militants are killed in encounters, youngsters risk their own security and travel under curfews to catch a glimpse of the slain militant. Going to the funeral and participating in the procession is akin to making a political statement.

Women can also be seen participating in funerals. In fact, when five men were killed in Shopian recently on March 5, the incident triggered a social debate about the role of women in the resistance movement. Often, the martyrs are showered with almonds, flowers and candies by elderly women who gather outside their homes hymning farewell songs as if welcoming a groom.

The slogans that reverberate during the funerals also show the importance that funerals have taken on: "Asalam asalam aye shaheedo asalam. Aaj tere mout pay ro raha hai asmaan. Ro rahe hay ye zameen ro raha hai asmaan [Peace be with you, O! martyr. Today

upon your death the sky and earth are showering tears]; and "Shaheed ki jo maut hai wo qoum ki hayaat hai

[The death of martyr is hallmark of the nation’s eternity].

Political commentators say that in January 2016, only a few thousand people including party-workers turned up at the funeral of Mufti Syed, Jammu and Kashmir’s formal chief minister, while lakhs of people gathered at Burhan Wani’s funeral on July 6, 2016. "The gathering of people at Wani’s funeral was a clear referendum against India," claims Syed Ali Geelani, a senior resistance leader.

And from the state perspective, "The weak turnout at Mufti Syed’s funeral is a matter of concern for mainstream parties in Kashmir," says SM Sahai, the former intelligence chief, to a gathering in New Delhi.