Working with one’s own hand or relying on apprentices or outsourcing art; both approaches are fine because in art there is no one single method or process

Decades ago, in my final year at NCA, when I arrived home late and washed my hands before sitting for dinner, my father always inquired if I was coming from an educational institute or a factory. The whole sink would be tainted with a grimy substance, the residue of colours and wiping of printing plates at the college. I was preparing for my Degree Show.

Students still smear their clothes and hands with paint and chemicals of all sorts, no matter if they are making sculptures, paintings or prints. Compared to these young and emerging artists, established figures in the present art world hardly indulge in the act of ‘making’ in the literal sense. Instead, they have devised plans for their works to be executed either through studio help, using a computer or to be produced at a far-off place. When we see the works of say Rashid Rana, Hamra Abbas, Adeela Suleman, Mohammad Ali Talpur, and several others, we know they have created these works without physically executing them. Like architects who draw plans and then a team of draughtsmen and civil engineers executes them with the help of contractors, masons, labourers, and other technicians, there is a team of workers that fabricates the works of these artists.

On the other hand, there are individuals in our midst who pick a brush loaded with paint, mould clay to make a form, cast, carve or weld a sculpture, print a lithograph or an etching, tear papers to compose a collage or gather objects for assemblages. In the process their fingers are stained with paint, oils, and dyes, or strained after constant use of hammer and chisel, or chemicals are stuck in their nails doing a fiberglass piece. After their work is complete, their hands and clothes do not look different from any ordinary worker who earns his wages by toiling at a building site.

Some artists prefer interacting with their materials and final product. Several like to inhale the smell of turpentine, a few become oblivious to the odour of chemicals used in the process of fiberglass, and many enjoy handling bitumen, thinners and acid for preparing their zinc or copper (printmaking) plates. On the contrary, there are artists who have no mark on their fingers or clothes, yet they produce works which are as effective, impressive and important as those made by the hand.

At a recently concluded artists’ residency, this divide became obvious, since some participants employed technicians who ‘constructed’ their works while others preferred their hands to prepare artworks. Both processes did merge at some point, but in some instances an artist was purely a planner, while in others he was the master of his work at every step, changing it at different stages till the piece was complete.

Both approaches are fine because in art there is no one single method or process. Art-making is generally considered a means of enjoying freedom but, like many other human pursuits, it entails a contradiction. Both approaches -- working with one’s own hand and relying on apprentices or outsourcing it -- demand some reflection. It is connected with market. A village potter in Mexico produces ten bowls on his wheel in one day, all slightly different from each other, purchased by his neighbours. But if he needs to supply 10,000 pieces in one day for a larger community which lies outside his village, he needs to sell his design to a factory.

It is not surprising that artists who are using apprentices etc. to make art are mainly those who have been exhibiting internationally and regularly. The pressure to produce works for various exhibitions around the year demands a group with expertise that can fabricate works as per the artist’s ideas, plans and directions. However there is a difference, mainly to do with manual and mechanical input. Some artists finalise their work and it is executed mechanically at a workshop, foundry or factory, while others employ manual help and incorporate their input only in final stages.

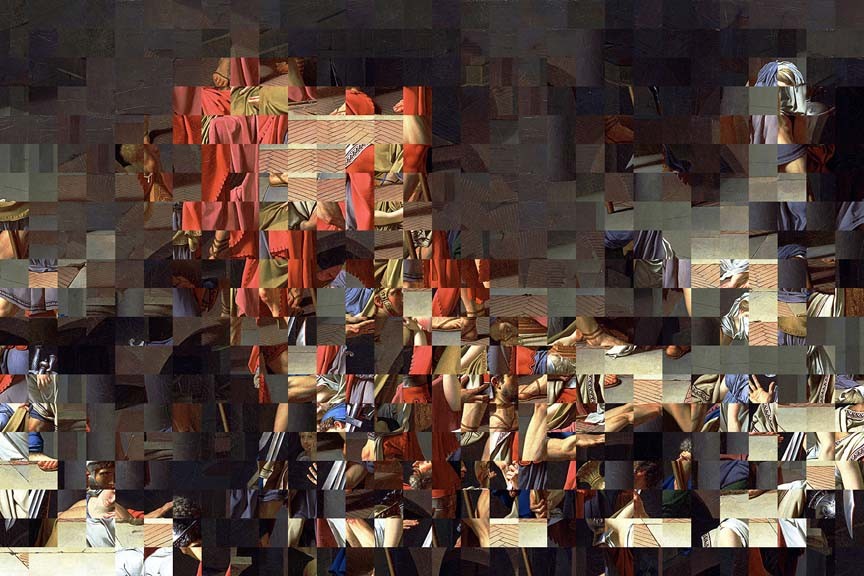

One is intrigued how the artists of today have joined their predecessors from Renaissance and Mughal courts to bypass the demand and definition of authenticity. During the Renaissance as well as in Mughal workshops of miniature painting, it were the pupils, apprentices and young artists who helped produce works which are now admired as a canvas by Peter Paul Rubens, Diego Velasquez, or a master painter serving Akbar the Great.

Do we need to know the names of those assistants? How much was their contribution in terms of aesthetic decisions? These issues resurface today when a person insists on knowing the identity of collaborators who have helped in shaping a work of art.

There is a subtle difference between a studio assistant, technical help and collaborator. Because the former two work strictly in accordance with an artist’s plan, while the latter may add new elements into the imagery, content and intent of the artwork. If the contemporary artists prefer to employ services of others, it is because the scale, medium, and technique are not possible by a single worker. Besides, what a person looks at is the ‘label’ or the name of the artist, regardless of whether the canvas was painted by him or someone else, or the bronze piece was cast by him or his workers.

This leads to a difference and distance between the concept and its physical form, although the two affect, alter and enhance each other. As for the artists, with their manicured hands, treated skin and designer outfits, they appear part of a corporate or business fraternity. But they are still concerned about the process of the work that comes out of their studios and is seen at museums, art fairs and biennales.

In that sense, it is not the touch of a maker’s hands or the list of his helpers’ names that is essential to appreciate an art work; but it is the idea which ‘takes a work into the realm of art’; the rest are just details.