Human reality, being complex and layered, can only be conceived imaginatively and not through analytical methods of history

The question of how diverse narratives of history and culture have influenced Urdu fiction and the latter’s response to these narratives, particularly the ones constructed and disseminated by political authorities, was the central point of discussion in a session on Urdu fiction at the second Gujrat Literary Festival (GLF) held last week.

The GLF was a project of the Gujrat University in collaboration with a two-person team comprising Dr Sheeba Alam and Tosheeba Sarwar who had also helped organise the Faisalabad Literary Festival.

One session on Urdu fiction was moderated by Asghar Nadeem Syed while Masood Ashar and this writer were on the panel. Opening the discussion, Syed remarked that classical and modern Urdu fiction is deeply embedded in indigenous culture and has recorded all major events of our political history. Ashar was of the view that ever since the progressive movement initiated in mid-1930s began, Urdu fiction has

responded to major historical events and occurrences in its choosy fictional manner. Here is a summary of my contribution to the discussion as well as some afterthoughts on the subject.

At first glance, literary fiction and history indeed appear to be at loggerheads. As the word fiction suggests, it is a work of imagination -- an untrue, unreal, purely fabricated story. On the other hand, the discipline of history cannot be imagined without facts that are verifiable by authentic sources and abide by laws of causality.

However, both fiction and history are like kawakib (stars) which, in Ghalib’s words, conceal their reality at first glance. Interestingly, reality is a thing that is desired and sought both by fiction and history alike.

While history seeks to arrive at reality by culling out verifiable facts from various sources, fiction aims at embracing reality through creating pure imaginative events or imagining historical events. History stays bound to what happened in the past while fiction is attached with both what happened in real life and what could be imagined. On this score, fiction enjoys a much wider space -- to seek and play with reality. Reality is a complex, elusive, multifaceted and indescribable thing. It is quite imaginable that the reality of social or political life of a particular period as contained in history books is conceived as a naïve view of reality or even disapproved by fiction, based on historical narratives of the same period.

As the histories of modern societies reveal, the reality offered by unbiased, assiduous historians has been upsetting for political authorities. So they try to control history through a range of acts and strategies: they conceal or mutilate facts, cunningly reinterpret occurrences, and even fabricate events in the name of history. No doubt some conscientious historians step forward and challenge the versions of ‘controlled reality’ by offering counter versions of history.

Every true historian, regardless of whether he or she is conformist or non-conformist, is bound to come up with a monolithic yet correct and authenticated concept of reality. So, a host of layers of ‘human reality’ of a particular era go missing in history. Fiction, on the other hand, aims at conceiving and describing the indescribable, multi-layered, complex human reality through true historical or imaginative events, characters and their emotional and psychological responses. Human reality, being complex and deep, can only be imaginatively conceived; it cannot be fathomed by rational, interpretive, analytical methods of history.

Where fiction is based on some historical narratives, it emerges as an alternate version of history. Here we must draw a distinction between counter and alternate versions of history. Counter versions oppose an already existing version of history, by refuting the latter’s claims and employing the same method of enquiry. On the other hand, alternate versions proffer something new without refuting existing versions.

Postcolonial historians, the likes of Ranajit Guha, Romila Thapar, Harbans Mukhia, Irfan Habib, Mushirul Hasan, Ayesha Jalal and others have offered counter versions of colonial histories written by colonial masters or their collaborators.

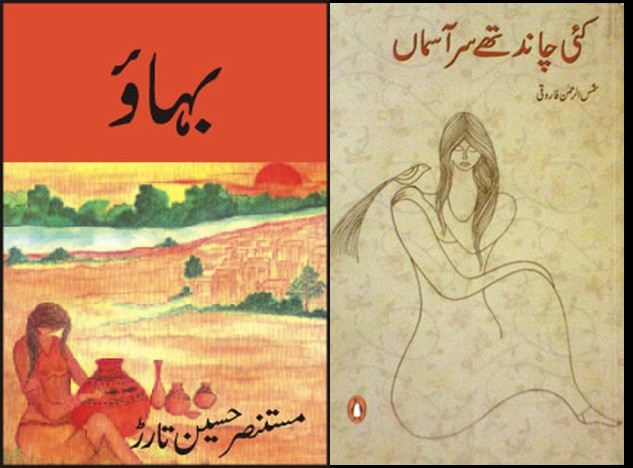

At the same time, postcolonial Urdu fiction presents alternate version of colonial history. In Shamusur Rahman Faruqi’s novel Kai Chand the Sar-e-Aasman, the historical character of Wazir Khanam appears as an alternate, dynamic, bold, self-conscious image of an Indian woman. Mustansar Hussain Tarar’s Bahao also suggests an alternate version of the 5,000-year-old [Pakistani] culture by struggling against the ‘cultural dementia’ through a story of a civilisation that had to battle death, brought about by the gradual drying out of Sarsavati River. In the same vein, Masood Ashar and Zahida Hina’s Urdu short stories present alternate historical versions of East Pakistan tragedy.

Ikramullah’s novelette Pashemani also offers an alternate version about the partition of Punjab. Historical accounts of partition simply tell us that more than 150 million people were brutally killed and displaced. But this tragedy experienced by the whole being of people is missing in books of history. Ikramullah’s novelette skilfully describes how Ehsan and Saeed, two lifelong friends, experienced trepidations, anxieties, forced displacement and all sorts of sufferings engendered by partition. Similarly, Manto’s ‘Toba Tek Singh’ is a classic example of how terribly the partition of Punjab tarnished the entire existence of people.

That Urdu fiction has filled the lacuna and gaps of history is well exhibited by Manto’s ‘Allah ka Bara Fazal Hae’ published in the second issue of Urdu Adab, a literary magazine edited by Manto and Askari which appeared in 1949. The direction in which Pakistan was heading remained missing in historical accounts of the period but Manto’s Afsana prophetically discloses that direction.

[God is great. The era of ignorance has been brought to a close. There used to be dance halls, cinemas, art galleries in every nook and corner. Now by the grace of Allah you can’t come across any poet or musician. All sorts of curses including music exist no more. You will not find any barber shop using razor anymore. However, halwa, the religious food of our religious leaders is available everywhere in abundance]The same theme was adopted by Ghulam Abbas in his long story ‘Dhanak’ in late 1960s. This story also narrates an imaginary yet not-historically-unbelievable story of a religious revolution in Pakistan -- a revolution that ultimately devastatesthe country.