The artist’s show at the Manchester Art Gallery testifies that a work of art, like a lark, is free to fly beyond the limitations of a passport, mark of a period or stamp of a practice

The case of Waqas Khan, the rising star of Pakistan in the international art world, is interesting regarding some important aspects of the present art scene. Everyone who had taught him at the National College of Arts (NCA) or studied with him during his four years at the Department of Fine Art would remember his modesty, pleasant manner and good nature as well as his struggle as a student of print-making.

Today, he is the most talked about artist of his generation outside Pakistan, with shows in museums and art fairs, and reviews appearing in reputed publications like The Guardian. Yet many members of the art community here still remember him as a struggling young man at NCA. They cannot deny his success and yet find it hard to believe in his artistic merits. For many, his recognition in the international art scene owes itself to his personal charm and his play of exoticism that includes a narrative of spirituality and his use of meditation, and his stress on craft (of making innumerable small lines constructed with tiny dots). The Western audience adores all of this and is said to expect this from an artist who comes from this part of the globe.

Some attribute it to the genius of Waqas Khan who recognised that there has been an overdose of identity, gender, and violence and the world expects something different, more soothing and sublime from the East; hence the reception and recognition of his work outside South Asia.

Whatever one believes in, it is clear that Waqas Khan casts doubt on the system and the structure of the art establishment and art teaching in Pakistan. A student who barely managed to pass the class, was always criticised by his tutors and got negative remarks from fellow students, has now emerged as the leading figure in art. Perhaps this is a fit case to re-examine, revamp and review our art education. The teachers at the oldest and the biggest art institution of the country need to examine their pedagogical strategies because an art school is essentially supposed to produce a successful artist. The fact that Khan has won international acclaim -- with his solo show at the Manchester Art Gallery included in the list of best art shows in UK (other being Dali and Duchamp at the Royal Academy of Arts London) -- means the conflict between local sensibility and international appreciation ought to be resolved as well.

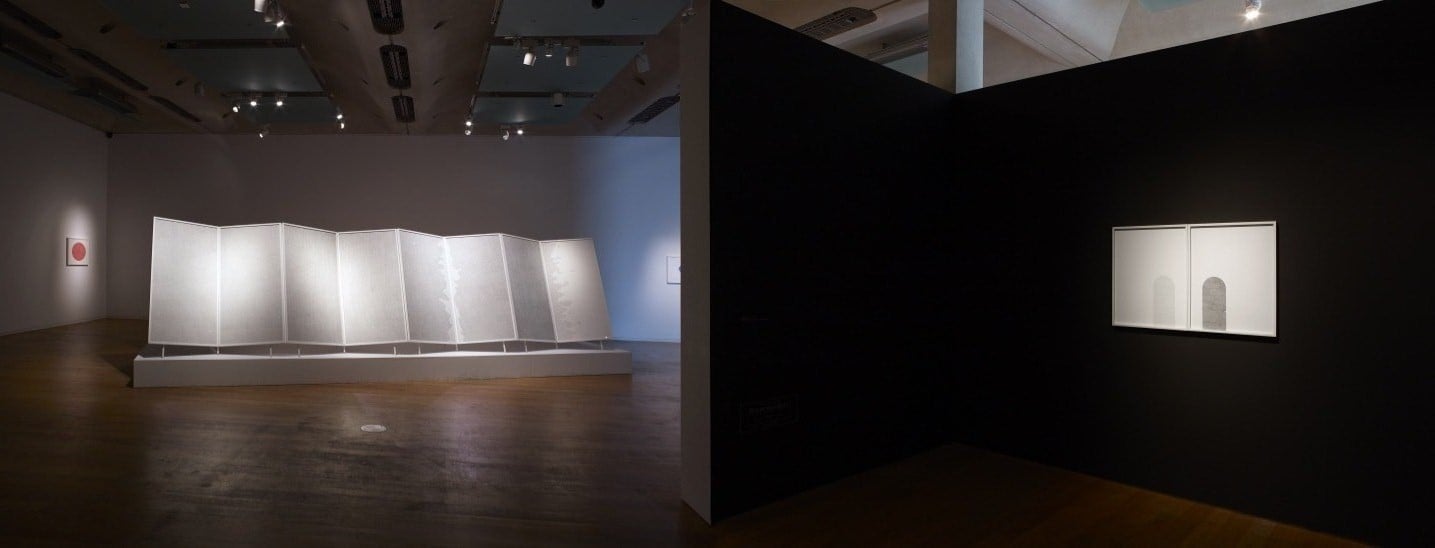

Even if it is not resolved, it should at least be addressed. One had a different experience at his recently concluded exhibition at the Manchester Art Gallery (Sept 30, 2017-Feb 25, 2018) from how one looked at the same works at his studio in Model Town Lahore. The scheme of installing the work, lights, scale of rooms, colour of the wall, all contributed towards creating a magical sensation. Marks made with points in white in a circular shape on a dark surface appeared to be suspended in space and were as luminous as the disk of moon. These seemed to have an otherworldly effect. The darkness around that particular piece (‘My Small Dancing Particulars’) enhanced the feeling of light coming from the work, rather than being directed on it.

In a similar way, his other work, a sequence of papers in different frames but joined as open pages of a manuscript (‘In the Name of God’), offered a sensation not much different from watching sea weaves, except that these were created with innumerable dots.

Likewise, his other relatively smaller works have a pictorial sophistication in which you spot an image and later it disappears, echoing the breathing of a human being. Khan controls that impact through his command on the selection of colour; varying shades of whites or imperceptible tones of blacks created that sensation.

A viewer from a different part of world may engage with and enjoy an artistic output with much more freedom and openness compared to how that creative personality is viewed by his or her compatriots. Many writers who have a wide readership around the world -- from Orhan Pamuk to Haruki Murakami -- are accused by their countrymen of writing for the Western audience by relying on exotica. But readers who enjoy Pamuk or Murakami do not care for local politics or criticism. They access the essence of work that transcends regional connections and communicates in a universal tone. What you read is not characters in Istanbul or Tokyo but yourself and people around you.

Reader who knows these works have been translated may not bother about the debates in terms of representation of indigenous culture for outsiders because they are amazed and enthralled by the power of the world constructed with the words of these novelists. For them, exoticism hardly exists because specific references are absorbed into general human conditions which can be identified by people from different continents. Similarly, the art of Waqas Khan is an example of a work levitating above its national, historical and traditional ground and entering into the pictorial hemisphere and imagination of a public without borders, local taste, or prejudice.

His case denotes that a work of art, like a lark, is free to fly beyond the limitations of a passport, mark of a period or stamp of a practice. It can still allure everybody from everywhere, like the works at the Manchester Art Gallery did.