Asghar Nadeem Syed’s debut collection of stories hunts for answers to big questions posed by the political, social, cultural and literary history of Pakistan

Failure is the destiny of partition-seekers. Those who seek a partition between fiction and fact are destined to fail. In ordinary life, facts can be sorted out from fictional things but in literary fiction boundaries of true and false, fantasy and reality or imaginative and real become blurry. Voracious readers of fiction would testify to the fact that as some fictional text touches its extreme limits -- stretching the imagination to its remotest borders to feign things otherwise unimaginable -- it begins to rub shoulder with facts.

What is imagined in and through a story doesn’t remain aloof from truths of life. Nothing is more mysterious than life. This doesn’t mean that we find a single truth in ordinary life and fiction wearing different attire. The truths offered by fiction are usually alternate ones.

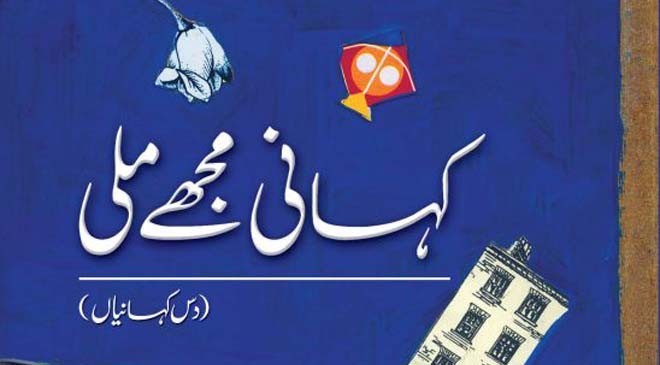

These introductory lines aim to epitomise the major themes of Kahani Mujhe Mili, a debut collection of Urdu stories by Asghar Nadeem Syed, a distinguished playwright, poet and columnist. He is known for TV dramas Khwahish, Chaand Girehan, Nijaat, Khuda Zameen Se Gaya Nahin and novelette Adhay Chaand ki Raat.

As the title Kahani Mujhe Mili suggests, the author goes in search of the Kahani and upon success, he embraces it. Syed’s search for the story reminds us of quests that the heroes of dastaans would indulge in. They would leave their homes to travel to distant lands in the hopes of treasure, or to embrace the princess of their dreams, or to find answers to life’s larger questions.

Syed’s story quest hunts for answers to big questions posed by the political, social, cultural and literary history of Pakistan. These answers are presented as alternate truths to official narratives about the country’s history. Syed’s stories are political in tone and nature alike. This doesn’t mean that his characters are essentially political animals having no existential and psychological life. The reality is that that both their existence and essence are wrapped in and shaped by political phenomena. Politics determines their destiny; political upheavals shape the emotional turbulence of Syed’s fictional characters.

Almost all 10 stories in the collection revolve around the three junctures of Pakistan’s political history: partition, the fall of Dhaka and the post-9/11 scenario.

Syed views Pakistan’s entire history through the lens of partition. To him, in one way or the other, the spectre of partition is ever-hovering around Pakistani imagination, intellect and life.

How partition brought suffering upon the people of this land has been overpoweringly narrated by the likes of Manto, Intizar Husain, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Krishan Chander, Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi and others in their short and long Urdu fiction. As a theme of fiction, some may argue, partition has turned into a cliché. Therefore, writing on partition would mean reproducing what has already been masterly produced. But the political facts being witnessed on either side of the border tell another story. From the Kashmir issue to the daily casualties along the LoC, from visa restrictions to the discriminatory treatment of minorities living in both countries, everything persistently reminds us that the woes of partition have not yet ended. So there is not only sense but also a justification to write on partition.

To Asghar Nadeem Syed, Manto and Intizar Husain are great fiction writers of Urdu who have skilfully narrated the miseries, pangs and anguishes brought about by partition. ‘Aik aur Toba Tek Singh’ and ‘Aik aur Shehr-e-Afsos’, two stories included in the book under review, suggest that what Manto portrayed in ‘Toba Tek Singh’ and Intizar Husain zeroed in on in ‘Shehr-e-Afsos’ still lingers not only in our memories but in reality as well.

‘Aik aur Toba Tek Singh’ is a story of an Indian Sikh spy who was captured by Pakistani intelligence forces and died in a Pakistani jail. The narrator brings his ashes to Indian Punjab to bury them.

Similarly, while Intizar Husain’s ‘Shehr-e-Afsos’ was written in the backdrop of fall of Dhaka. Syed’s ‘Aik aur Shehr-e Afsos’ is not a story of another ‘city of sorrow’ but another story of the same ‘city of sorrow’. The dead characters of the ‘city of sorrow’ relate a series of sorrowful events occurred after the fall of Dhaka. ‘Aik aur Shehr-e-Afsos’ narrates the miseries of Pakistani Christians killed in church attacks, the anguishes of parents collecting the remains of their children martyred in terrorist attack on APS Peshawar. They describe the inhuman and horribly immoral acts common people commit soon after some sad accident killing many people by collecting and snatching precious things from the killed ones.

The logic of narrating a story by dead people is unfolded in the following lines of the story.

The story seems to insist that the difference between alive and dead no longer exists. As per the Urdu idiom, the alive are ‘zinda dargor’ (in grave while alive). What a paradox and what a tragedy! Millions of people had to die to be liberated from the clutches of the colonisers while nobody knows how many millions have to die to save their land.

Kahani Mujhe Mili seems to assert that we, the people of South Asia, have not yet been able to transform the course of history. What this land witnessed during the colonial period is being continually observed in the postcolonial era. ‘Samandar Pe Kia Guzri’ is about the strategies adopted by neo-colonial forces to start business activities on the shores of a sea (presumably Gwadar). The story shows that New East India Company has arrived on the [Pakistani] coast, displaying techniques espoused by British East India Company in 18th and 19th centuries, which were a mixture of brutal and soft power. The story ends by showing that the natives are ready to initiate another freedom movement.

‘London 2050’ is another predictive text. It shows that in 2050 the ethnographic landscape of London looks like that of subcontinent. The population of Pakistanis, Indians and Bangladeshis has grown so much that they have enough representatives in the English parliament to launch their own PM. Here too, the malady of partition hovers behind the disputes about who would be the PM of England: a Pakistani Muslim, Indian or Bangladeshi? The story ends at an optimistic note when all three nations agree on the name of Sanwal, the son of a Pakistani poet and English lady.

‘Hamary Hero Wapas Kar Do’ is another insightful story. Written in the backdrop of tense Pak-Afghan relations, the story brings into focus the problematic nature of hero and the complex psychology of hero-mongering nations. The Afghan ambassador is shown demanding the Pakistan government to stop using names of their warriors, Ghauri, Ghaznavi and Abdali, as names of Pakistani missiles that are then dropped on their land. Understandably, the demand is rejected by Islamabad asserting that these warrior tribes have been assimilated into Pakistan.

This is the politics of signs, names, nomenclatures -- and semiotics. Signs have become more powerful, and more hazardous in many cases than the thing they represent. The politics of semiotics seem to have overthrown the real polity. At the end of the story, it is shown that Kabul also gets missiles from India and names them Ghauri, Ghaznavi, and Abdali in a bid to reclaim their heroes. Pakistan is shown protesting to Kabul to stop dropping missiles on its land that bear the names of its heroes.