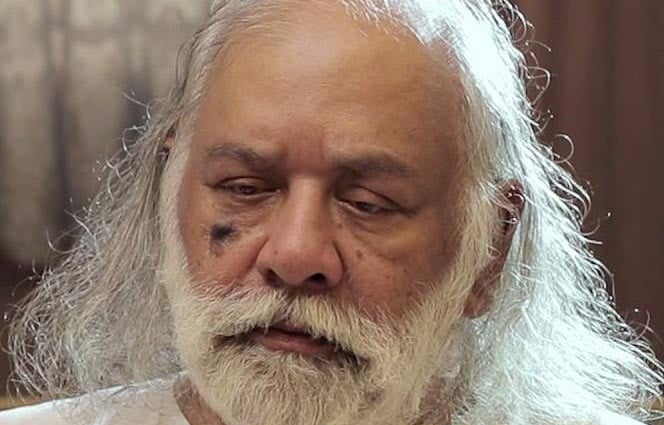

Away from the din of fashionable art circles was Shakeel Siddiqui whose genius lay in offering a deeper understanding towards the perception of reality

I had met Shakeel Siddiqui a few times but these were hardly meetings in the real sense. Exchanging glances, brushing fingers in brief handshakes, and being in the same room with other people do not qualify as personal encounters. Yet I don’t regret it. Had the artist, who passed away on Jan 11, lived more I know I would hardly get a chance to converse with him or visit his studio.

Meeting the artists is often a disappointing and boring exercise. Flaubert recognised this when he advised: "Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work". The death of soft-spoken and mild-mannered Shakeel Siddiqui has indeed come as a shock because now that swift eye-hand-coordination that created superb surfaces with sensitive layers of paint is no more.

Siddiqui has left the world after creating a parallel world which cannot be cloned or colonised. We may not have another painter with the same vision, sensibility and sincerity. The artist didn’t mingle with fashionable art circles. Actually, one reason also was that for years he was based in the UAE.

The longest I saw him, and that too from a distance, was when he was teaching a course in photorealistic painting at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi. I paid my respect to the painter who from an early stage of my life had impressed me. I spotted exercises of students, placed on easels, against the wall or put in their cubicle, all depicting windows or some other section of a building. But these did not seem like students’ work due to the maturity of skill and sophistication in paint application. The works were not merely replicas of what was there in a neighbourhood; these were emerging artists’ response to reality.

I don’t know if Siddiqui ever taught regularly at an art school but I believe that a good artist is essentially a good teacher. He does not teach through words but with examples of his works. Khalid Iqbal was one such teacher who taught generations of artists standing alone in scorching sun and rendering what he saw in front of him. Likewise, Zahoor ul Akhlaq influenced a number of artists through what he produced in the solitude of his studio. His perpetual search in trying to find a language that describes our times continued in the practice of many artists after him.

Shakeel Siddiqui also inspired artists by making works in a genre that exists almost on periphery. In a country where abstraction was once ridiculed, it is now accepted as a sign of modernity leading to various valuable experiments in form, medium and technique. Siddiqui’s contrary example certifies that one can still pursue one’s individual vision despite changing trends. It conveys that in art, multiple voices can coexist only if these convincing and confident.

The art of Siddiqui could be described as ‘avant-garde’ since it offers a different version to what is considered mainstream art. In the art world of Pakistan, like its social order, there is a hierarchy of genres. Misleadingly, artists who work in realist idiom are considered not as smart as those who deal with modern and contemporary vocabulary. Whereas it is not form but content that turns a work contemporary. Hence, many drippings of enamel paint to forge abstract surfaces are as forced and fraudulent as covering miles of canvases with clouds, plants, grass, village maiden or people stuck in narrow alleys of old towns.

On the other hand, the art of Siddiqui is different from the ordinary, and defies the superficial description of ‘realistic’ art. It is more about reality than realistic. Looking at his paintings, I always recalled Arthur C. Danto, the writer on art and philosophy, who dealt with the link between reality and its reproduction in art. In one of his essays, he mentions riding on a bus and spotting a painting of 10 dollars’ bill in a shop window (painted so convincingly that it looked pasted), which the owner of the bric-a-brac store sold for 10 dollars. I wish Danto had a chance to see Siddiqui’s surfaces because they reveal a lot more than what was in front of the painter.

He carefully selected his subject matter which must not be confused with his models, props or reference material. His work transcended beyond the mere rendering of details. One of the most important features of his art is his choice of visuals. Carefully selected images negotiate with the question of flatness, imagery and two-dimensionality -- for instance, a notice board with envelopes pinned on it, replica of a historical painting with its gilded frame, a door, they all reinforce the flatness of the pictorial plane.

It is not the craft of rendering that distinguishes Siddiqui as one of the significant artists of our history but his genius -- in composing views which offer a deeper understanding towards the perception of reality. In fact, these can be an individual’s way of perceiving and presenting the world. Like other professionals, artists too have a pair of eyes but they are kind of aesthetic dictators since they make us see how they had viewed the world once.

Whenever I come across a notice board, two panes of a closed window, a table laden with tea set, some books piled on a shelf, a picture frame, the art of Shakeel Siddiqui resurfaces and starts to mix with the concrete entities in front of me. I can’t see the world without his creations. Jorge Luis Borges talking about this phenomenon explains "[Oscar] Wilde said nature imitates art….. which is possible to the extent that art can teach us to see in a certain way".

Even though I never had the chance to converse with him, I feel I didn’t miss much because he is still there, alive, active and astonishing in the form of his painting at the Lahore Museum, the National Art Gallery Islamabad and in the homes of private collectors. Besides painting objects in front of him, he also painted himself which will remain with us -- for a much longer period than a human life.