Another rejoinder to the essays on the application of the British literary canon that argues how colonial ideology was part and parcel of this apparently ‘innocuous’ discipline of English literature

Mahboob Ahmad’s article ‘The Lingering Canon’ (published on these pages on November 5 and 12, 2017) predicted that the debate regarding Shakespeare’s dispensability would "startle, shock and offend most English departments in Pakistan". Something of the sort happened and his article managed to tease out an impressive response by Sibghatullah Khan titled ‘The Canon Question’ (November 26, 2017). Khan misconstrued Ahmad’s critique of the unparalleled reign of the English canon as an attempt to displace it to make room for its American counterpart.

Khan seems to have taken an affront to Ahmad’s observation that Pakistani English departments suffer from "intellectual stagnation", and has thus offered some evidence to the contrary. He has also, almost vociferously, advocated for "developing our own canon of Anglophone Pakistani literature" without the overarching influence of Western writers grandstanding on issues that are best addressed by Pakistanis themselves.

Conspicuously missing in Sibghatullah Khan’s article, however, is his engagement with the very basic premise of Ahmad’s article: that [Pakistani] "universities should constantly engage and dialogue with past, present and future." Although Khan engages with the question of the discipline’s future -- development of "our own canon of Anglophone Pakistani literature" -- yet, the issue of the discipline’s past is completely ignored. I would like to bring this crucial issue to the fore and argue in favour of a more critical engagement with the discipline’s past.

If we keep the colonial past of the discipline in mind -- the fact that English literature was a "major institutional support structure of colonization", as Gauri Vishwanathan has conclusively argued in Masks of Conquest -- then Shakespeare is not important just for his literariness, but also because of his institutionalised persona in colonial universities, of which our English departments are an offshoot. Shakespeare, then, is not just an artist but an epitome of Anglo centricity. The problem, then, is not Shakespeare, the writer, but the appropriated, eulogised and institutionalised Shakespeare who had the backing of the state’s ideological apparatus for over 150 years.

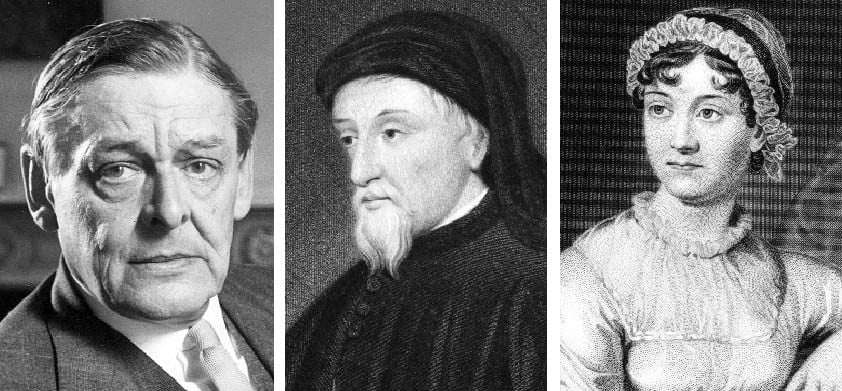

Shakespeare is not just one Shakespeare, the innocuous literary genius who is uncritically evoked in critical pedagogical debates; but, along with other literary stalwarts from Chaucer to T.S. Eliot, part of the grand colonial project. He was a crucial cog in the massive colonial juggernaut whose objective was to cower native students into accepting their cultural inferiority and embracing "inherent" superiority of the English culture. In this unequal transaction, the native students were also alienated from their actual socio-political and historic context. In their historical memory, plundering and looting Clives were replaced with literary lives of Spensers, Miltons and Shakespeares. They became the surrogate Englishmen for their criminal compatriots.

Read also: The literary canon

But what about their literary merit, some of our colleagues would protest. I would respond by sharing with them a few glimpses from the primary data that I have garnered from 135 years of the MA English programme’s history at Punjab University. Aesthetic engagement with Shakespeare and other English writers was only a partial concern, probably less in significance than the other objectives that the colonial administrators and educationists had in mind. Consider these questions from MA’s paper on poetry that was conducted in 1918: "Illustrate Shakespeare’s relation to national [English] history". "Show the truth in the statement that Shakespeare had a keen sense of national history". An inevitable connection was thus forged between Shakespeare, the literary genius and "the great English nation".

Similar examples are endless and even a basic perusal of this data allows us to see how colonial ideology was part and parcel of this apparently ‘innocuous’ discipline of English literature. In fact, the discipline was used as a conduit through which culturally imperialist ideas were inculcated in the native minds, their subjectivities were transformed and thus made more pliant for colonial purposes. For those who disagree, I offer the following question from the paper of Prose that was asked in 1884: "Explain the fascination of Macaulay’s style and write after Macaulay an account of the political events that took place in Bengal in 1756-1757". I am sure everyone can see the ulterior motive for asking such a question. Literariness was thus not the exclusive reason due to which engagement with English literary stalwarts was facilitated, rather it was their remarkable political utility that led to the establishment of the discipline. The pre-eminence of the English canon continues to persist in the discipline perniciously in the name of universalism. This has to end.

Read also: The literary canon – II

And yes, replacing Shakespeare or the English canon with Poe, or O’Neill, Frost or Whitman would not be of any help either. That too came about in the wake of increased American influence in the region, as one might speculate, in the run-up to US invasion in Afghanistan. A university, then, is not an isolated, ivory tower that has nothing to do with politics, but part of the Ideological State Apparatus and not even literary disciplines can stay away from such politics. When General Zia came to power in 1979, the very same year, Russell’s In Praise of Idleness, Mill’s On Liberty, Lawrence’s Women in Love and Byron’s Don Juan were "deleted from the Syllabus". It wasn’t just this military dictator who was fond of such banishments, even British colonial administrators found it convenient to drop T.S. Eliot from the curriculum during WWII, apparently, for his inconvenient critique of the Western civilization in The Wasteland. The belief, then, that textual engagement within literary establishments is not connected with what happens in the power corridors is a naïve belief considered anachronistic in the academic world these days.

As far as the issue of Pakistani Anglophone Canon is concerned, uncritical emulation of the English/American or Western Canon can never lead to the creation of a Pakistani variety. Every single category of writing, globally, that has emerged and established a niche for itself, has grown out of the stranglehold of the imperial/western theory. In Pakistan, the so-called critical works duly-anointed by Western knowledge-publishing complex, fail to move beyond the western critical-imaginative stranglehold. Without breaking this mould and without an intimate engagement with Pakistani realities (imaginations too), Pakistani writing in English will never be able to establish itself as a separate category of literature. In fact the whole desire to get acknowledged in ‘the eyes of the world’ as "Pakistani Anglophone Canon" is flawed. Literature shouldn’t exist in the first place to get anointed by some elusive, global literary establishment but should serve the human locale from where it emerges or to where it arrives.

Read also: The canon question

At the moment, however, much of what goes in the name of Pakistani writing in English is either hopelessly reductive or reveals a dissonance between the writer and her subject matter -- an artistic demerit which has political ramifications too. The loudest voice, however, seems to be of those who are simply in love with English and are not willing to accept lingering questions.

These anglophiles, uncritically in love with Shakespeare, call English "our own language" but are not willing to acknowledge the cultural imperialism that comes with such an approach. They are not willing to acknowledge the historical (read colonial) "privilege" that comes with this claim. Such a ‘privileged’ stance often leads to writing that is pretentious, aims for the English condition and sneers at every reminder about the culture and people who exist close by.

This privileged clique overemphasizes the cultural productivity of the English-speaking elite of the country and calls their fascination with English, our country’s fascination with it. Such groups celebrate the likes of Jane Austen and would love to call our country "Austenistan". Perhaps we should learn something from the poetic conversation on the matter that took place between two African poets:

Molara Ogundipe:

…ask why the

austen folk carouse all and do

no work -- play cards

at noon and dance the while

-- the while the land

vanished

behind closures…

Felix Mnthali:

…if we had asked

why Jane Austen’s people

carouse all day

and do no work

would Europe in Africa

have stood

the test of time?

and would she still maul

the flower of our youth

in the south?

Would she?

Your elegance of deceit,

Jane Austen,

lulled the sons and daughters

of the dispossessed

into a calf-love

with irony and satire

around imaginary people.

Eng. Lit., my sister,

was more than a cruel joke --

it was the heart

of alien conquest.