The similarities and differences between nations seem to be the core concern in Reena Saini Kallat’s work, currently on display at Manchester Museum

Flying to another country, you look out the window and realise that, despite national demarcations, the earth underneath is one. From a high altitude, you cannot figure out what tree belongs to which country, when does a green field fall into a different state, which part of the river belongs to another nation, and what line of national boundary crosses a mountain covered in snow.

A Pakistani citizen, crossing the border at Wahga/Atari to go to India on foot, spots the ‘border’ in a physical form, a thick strip of white colour. Maps and boundaries between countries are often virtual. But while stepping physically on a line of map and crossing it with all the documents in hand, hostile questions asked, body searches done, one is bound to notice the birds, clouds, and wind moving from one state to the other without much ado.

These boundaries are man-made, superficial and subject to change. Yet they are crucial for those who are trying to leave their homeland for another country, sometimes failing. Realisation of the borders being arbitrary becomes more pronounced when one encounters citizens such as Palestinian and Israelis, Kashmiris on both sides, Bengalis from Bangladesh and India, North and South Koreans, and Arab from various Arab states. Of course, there are differences but there are similarities between them too.

The matter of similarities and differences between nations -- which divide them and yet join them too -- seems to be the core concern in Reena Saini Kallat’s work, currently on display at Manchester Museum (part of North South Project). Kallat is an Indian visual artist who lives and works in Mumbai. An extensive body of work, these pieces in different formats offer the missing link between territories which were one before emerging as two different countries.

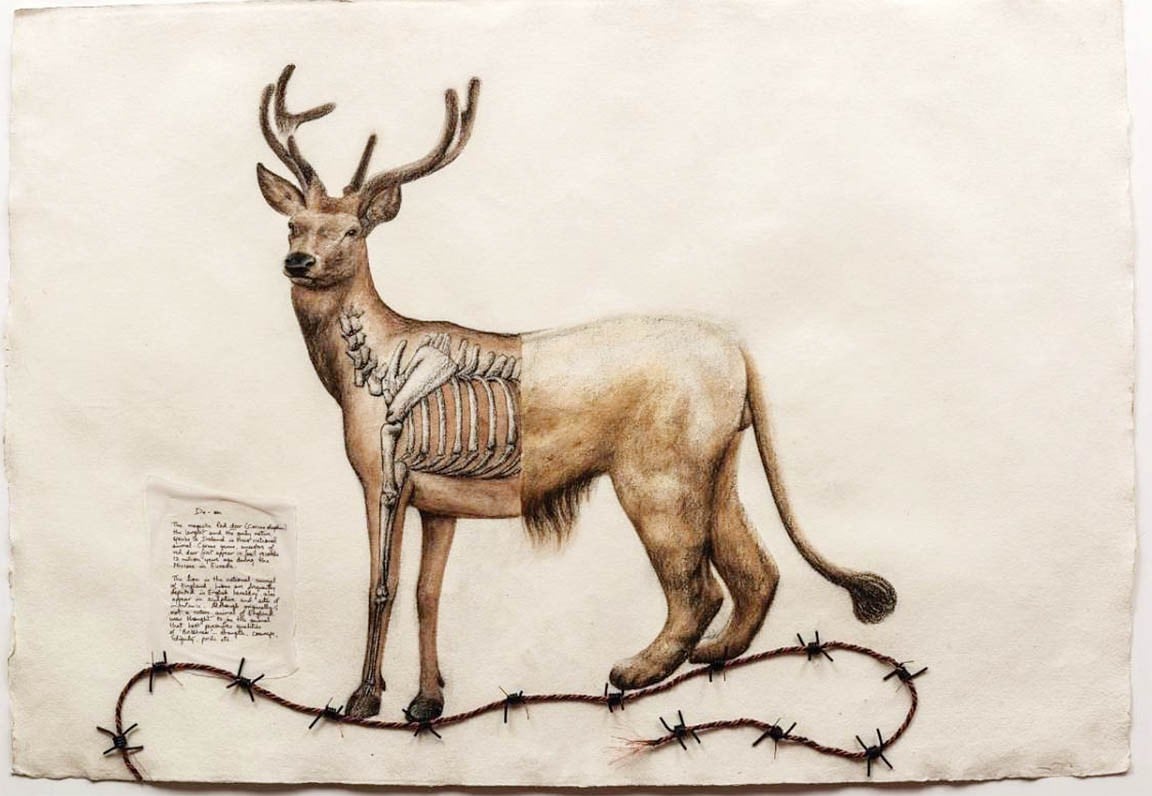

In a series of works on paper, which look like natural history drawings, text book illustrations, stamp designs, Kallat creates a range of hybrid species, joining two birds in the middle to make an unusual creature, mixing two reptiles, and connecting the bodies of two animals as a third entity. Looking at these remarkably rendered drawings, one ponders upon the impossibility and probability of these situations. Not far in future, one may get an animal like those presented in Kallat’s imagery, much like our recent past that produced countries that did not exist before. Kallat introduces skeletal structure in some of these, thus indicating the corresponding elements/content between different species.

Simultaneously, Kallat cuts and combines trees of two kinds into one. Like animals, which are not privileged to have a passport or any document to confirm their nationality (except a recent news item about Sindh Government’s decision to issue identity documents to animals in the province); plants are not part of a political division of geography. Through history, seeds travelled and you see date trees in the Middle East, as well as in Sindh and Multan; mangoes grow in India and Pakistan along with South America, strawberries are cultivated in countries like Pakistan besides many countries in Europe, and so forth. In her work, one comes across a merger of trees which critiques the system of divide that humans have developed for everything they use and own.

In these works with flora and fauna, from singular images developed into composite visuals, the artist creates an ideal -- joined but disjointed world; a sort of heaven of misfits, or a paradise of paradoxes. Here animals, reptiles, birds with split species roam in a landscape that is dominated with trees that have two different portions. Only clouds, sky and water is indivisible, but the rest is cut and ‘unnaturally’ composed.

This ideal, or deplorable, world is created with the precision of transcriber of encyclopaedia entries. The tone of depiction is distant, dispassionate, yet detailed, almost like a book illustration on zoology and botany. This body of work certainly does not deal with animals or plants; the images based on these entities, instead of a fantastical narrative, are about the political divide, mainly between India and Pakistan. A partition remembered due to carnage and exodus of a great number of refugees. However, the travellers of one country going to the other find more similarities than differences. Yet they are ‘enemies’ at some point of their histories and in the minds of some citizens, with many restrictions imposed on the free travel of individuals on both sides.

Kallat weaves her narrative in a way which signifies that maps and (history) books are means to segregate human beings. In the name of security, identity and history, invisible walls are erected between people, who share the same sunshine, rain, fragrance of flowers, breeze -- and, in many cases, features, languages, relationships, love, happiness. Yet they are far apart.

The matter of being similar yet opposite -- like a mirror image which is the replica of a person but on the opposite side -- is best rendered in two works, in which allegedly a spy pigeon from Pakistan was captured by Indian authorities or an Indian drone was intercepted by Pakistani government. Kallat creates visuals in the form a drawing and sculpture, accompanied by press reports that suggest the panic and paranoia on the basis of patriotism. The limit of patriotism is again addressed in an installation (part of the ‘Memories of Partition’ at the Manchester Museum. Here she produces the border gates between India and Pakistan, but one with two different parts. Each section adorned with each state’s national emblem. Weaved in thread, and joining together, this work conveys the problems of our times. The lines made by men (powerful politicians, bureaucrats, generals, but all men) are challenged through a different mode of image-making: weaving that has been associated with women in the past.

With its complexities, the work of Reena Saini Kallat comes from and refers to a specific region (South Asia). But it deals with issues that are global, and concerns that are universal. Like countries, continents and territories, each of us are also spilt into different nations and notions.