Understanding the doctrinal aspects of Sufism

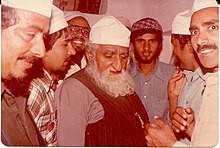

Pir Qamar-ud-Din Sialvi (1906-1981) wielded extraordinary power and authority during his tenure as the Pir of Sial Sharif. He was a staunch supporter of the Pakistan Movement; therefore, he lent unflinching support to the cause for promulgating laws based on Sharia in Pakistan in true spirit.

Immediately after the establishment of Pakistan, he vehemently pleaded to Quaid-i-Azam for the implementation of Sharia. That espousal of Sharia in preference to syncretic and inclusive values, that had been intrinsic to the Chishtiyya order in the medieval period, stood starkly null and void under Qamar-ud-Din.

This puritanical tilt had its glaring illustration in Chishtiyya castigation of the Ahmadiyya movement, which emerged in 1889. Another renowned Chishti Sheikh, Mehar Ali Shah of Golra Sharif (1859-1937), issued a takfiri fatwa (verdict to denounce apostasy) against the Ahmadi community. Prior to that, no precedent ever existed of such a takfiri fatwa originating from a Chishti Sufi. Likewise, then the Sialvis condemned Ahmadis and participated in the Tehreek-i-Khatam-i-Nabuwwat (movement for the finality of prophethood), an anti-Ahmadi organisation in the early 1950s.

Thus, for the Sialvis, exclusion on the basis of denominational difference became an important postulate of the Sharia, which came to take precedent over the more traditional ties of tariqat.

As such the Sufi-Alim divide ceased to last, with these two traditions being gradually brought closer together. Emphasis on foundational text and their literal meaning came to punctuate Islamic life across these categories. In the age of Chishtiyya revivalism, the diffusion of Chishti teaching was carried out through theological scripture on Hadith and Fiqh. Besides the concept of imamat (held as an important postulate of Shia denomination), Hadith and Fiqh represented a fundamental source of friction separating the Sunnis and Shias.

For instance, the difference between them and relation to ascertaining the authenticity of Hadith is very striking. From eighteenth century onwards, the importance of Hadith as a source of Islamic epistemology and law was reinforced in India. Jamal Malik, Muhammad Qasim Zaman and Francis Robinson in their respective writings have pointed to that development; Francis Rosbinson particularly delineates two changes bringing about transition in learning "from the rational science to transmitted sciences " and even more significantly "the complete rejection of the past scholarship". Thus Indo-Muslim civilization drifted away from what Robinson has called its "great traditions", most probably in sense of a civilization that originated and subsequently blossomed in the Iranian, Temurid and Mughal world, and, gravitated instead towards what he described as "the pristine inspiration" of Arabia and the first community at Medina.

Read also: Religious modernism and Barelvi creed -- III

It is equally important to note the change in the nature of the Pir-Murid relationship, as closer contacts between the Sufi and the Hadith scholars resulted in "more stress being placed on the doctrinal aspects of Sufism". Another point that Robinson propounds pertains to the Holy Prophet "as the perfect model for human life" which became the focal point of "South Asian Muslim piety".

For Barelvi piety, the Prophet was even more central, and Ahmad Raza Khan’s wujudi formulation of noor-i-Muhammadi cemented the Holy Prophet’s centrality in the religious sensibility of South Asian Muslims. Thus the personality of the Prophet and emphasis on Hadith as an important part of the foundational text created a new Islamic oeuvre in which the significance of the saint and shrine substantially receded.

In that socio-epistemic scenario, the Sialvi pirs embraced the sectarian, exclusionary mode which contravened the essential ethos of Chishtiyyas embedded in local tradition.

The Sharia-centred approach of Qamar-ud-Din Sialvi drew him closer to General Zia-ul-Haq. Given the denominational inclination of Zia-ul-Haq, it is interesting to note that a Barelvi Pir extends unequivocal support to a military dictator like Zia. Qamar-ud-Din’s 125-page book Mazhab-e Shia, published in 1957 provides a testimony to his condemnatory stance against Shia, that is a clear deviation from inclusivity that the Chishtiyya order and the Barelvi creed is known to have stood for.

Read also: Religious modernism and Barelvi creed -- II

More ironic is Qamar-ud-Din’s initiative of establishing a Shia Shanasi Centre which was meant to produce polemical literature against the Shia denomination. He also took parts in manazras (polemical debates). It is important to mention that the outcome of manazra had a profound bearing on the people inhabiting that vicinity and its surrounding. A large number of people tend to change their denominational faith in the wake of that polemical debate. What has been witnessed is that on the call of the victorious party, the whole village was converted from one denomination to the other.

Coming back to Qamar-ud-Din Sialvi, it must be highlighted that in the 1974 anti-Ahmdiyya campaign, Qamar-ud-Din took part as the president of Jamiat Ulema-i-Pakistan with extraordinary zeal. Qamar-ud-Din passed away in 1981 in a road accident. Since then, Sialvis were confined to the local vicinity opting to remain at a safe distance from any political or religious controversies. It was only the Faizabad sit-in by the Barelivs that Qamar-ud-Din’s successor Hamid-ud-Din came under a media spotlight.

What is overridingly important is the postulate of Khatam-i-Nabuwwat which has caused tremendous stirring among the Barelvies. That primarily was the cause which incited Mumtaz Qadri to assassinate the then governor Punjab Salmaan Taseer. Qadri’s hanging infused fresh lease of life among the dormant rank of Barelvi movement which came alive under the leadership of Khadim Hussain Rizvi. Ironically, however, all the Mashaikh gave a nod of approval to Rizvi’s imitational mode but none of them has so far questioned his leadership.

Read also: Religious modernism and Barelvi creed

The only one throwing down a gauntlet to Rizvi was Dr Asharaf Jalali who like Rizvi is a cleric himself. The interesting inference which one can draw out of the prevailing situation of the Barelvi politics is that clerics have come to hold precedence over the Mashaikh, the latter being reduced to the second tier leadership of the Barelvis.

One may argue that the present-day Mashaikh are starkly devoid of the requisite charisma that used to be the hallmark of their forefathers. Therefore, in this particular scenario, the professional clerics have come to the centre-stage of religious movements pushing the Mashaikh to the backseat.

The evolution of Barelvi movement in the modern era appears to be exactly like the evolution of Deobandi creed.

(concluded)