In Meher Afroz’s recent exhibition at Rohtas 2 Lahore, one can detect the artist’s quest to investigate the essence of life

Pakistani art is caught in the midst of monochrome with many artists using black & white or single colour for their imagery. A number of works by Lala Rukh, Waqas Khan, Mohammad Ali Talpur, Ali Kazim, Noorjehan Bilgrami, Farida Batool, Adeeluz Zafar, Hasnat Mehmood, Imran Channa, Ayessha Qureshi and several others are rendered in varying shades of greys or in one colour. In a sense, these hark back to the aesthetics of Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Anwar Jalal Shemza who, inspite of applying a range of colours, treated their painted surfaces as pages of a book (with text inscribed in a singular black colour).

There could be other reasons for preferring lines and forms instead of playing with a variety of colours. If black & white films and photography are regarded as classic, serious and subtle, a number of works executed in singular colour also offer this illusion. For many, colour is a frivolous notion, not much different from the term ‘colourful man’.

Away from these assumptions, the decision of not choosing colours and refraining their palette to one hue is related to artists’ focus on form (made up of lines and shapes) and content which, like the text of a book, can be read -- compared to colours that are enjoyed on a sensuous level. Hence the element of ‘reading’ is common between works of monochromatic sensibility and the lines on the page of a book/manuscript, both to be accessed in a cognitive state.

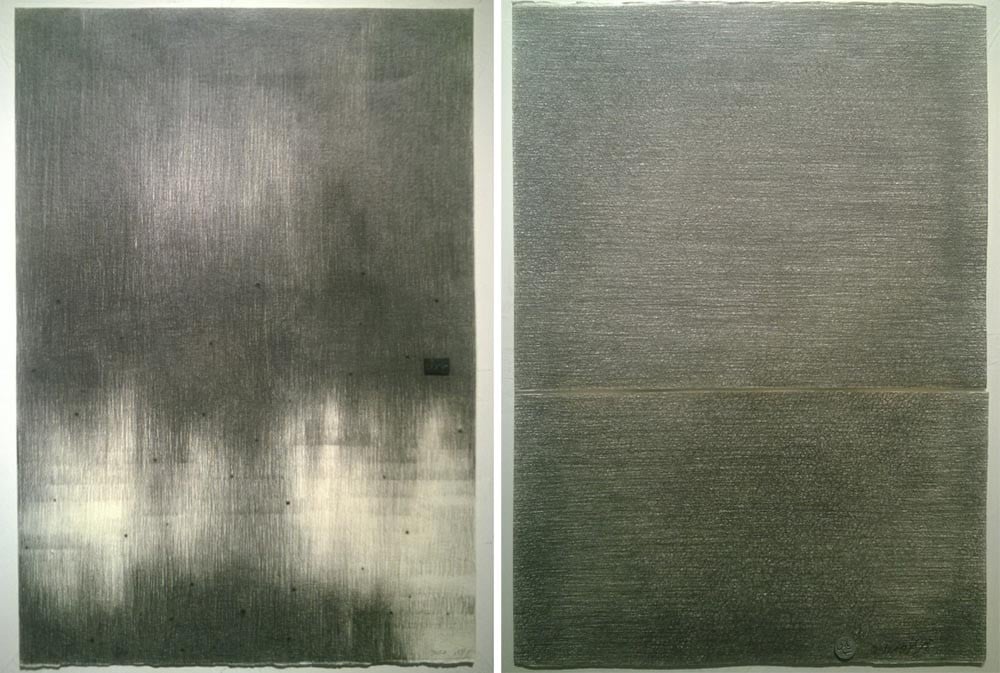

However, while reading a book, one is bound to be carried away with feelings, emotions and passions caused by those mechanical shapes composed on a page. The subtle difference between passion and precision, dealt with by many artists in Pakistan, is again experienced at the solo exhibition of Meher Afroz (‘Aap Beeti’, being held from Dec 15- 30, 2017 at Rohtas 2 Lahore). Created with graphite on archival paper, the works offer multiple variations of grey tones, enhanced with mixed media in two works.

Afroz reflects on her works: "The fabric of my life-story is woven with the emotional transformations of the decades’ long journey as an artist". Each of the eight works in the exhibition has one Urdu word placed in the otherwise abstract composition. These words if translated are about silence, distance, journey, indifference and love. But if a person knows the language, the connotation of these words supersedes one meaning, like ‘Masafat’ that can be translated into distance and also alludes to the pain of that passage. Or ‘Sakoot’, which can mean silence like ‘Khamoshi’, but the former is more about ‘the absence of voices/sounds’ than the latter suggesting ‘not speaking’.

Talking about these words, Afroz narrates her father’s stance on the condition of a new country when the family migrated from India to Pakistan in 1972. When we look at the work of Meher Afroz, we get a glimpse of what could have happened to a sensitive person who was uprooted from her homeland and came to a new country. Her inclusion into that community and her acceptance into a different environment must have been tasks beyond one’s imagination and calculation. Yet Afroz made a mark by reverting to the seals of Indus Valley Civilization; this was a way to reconnect and relocate herself to a different territory.

With these earlier excursions, Afroz soon found solace in the realm of art, her real home, an entity comprised of visual sensations and pictorial pleasures. Her later work comprised references from Muslim history as well as memory of a cultural past that exists in the artistic forms across the indigenous population.

Meher Afroz merges historical reference as well as contemporary experiences, in order to suffice a narrative about displacement, disorientation, and distortion of history. In her work at Rohtas 2, Afroz concentrates on a private and personal story through her choice of words. Apparently, her father often mentioned these terms to describe life which she explains and identifies with. But she moves ahead and transcribes a life in lines and textures. In these works, one can detect a person’s quest to investigate the essential aspect of life.

For a young person, every moment, hour, day and week is important. But with the passage of time, let’s say when people are 50 or 60, each day diffuses and passing weeks are evaporated in that huge body of memory. What a person recollects then is the essence of life, experiences and ideas. Viewing the work of Meher Afroz one realises the artist has arrived at her quest to a perfect surface. Her previous interest in the art of Antonio Tapies, her experiments with different forms and materials have led to the present body of works (all from 2017) that are about translating a period of time on a piece of paper. But, like the process of every translator, the second language adds as well as restricts; in her work, one reads the limits of narratives. Because even if one removes the tags of words -- like silence, journey, distance, love etc. -- or switches them, the work still communicates.

What these works convey is beyond literal meaning or local reference. Her way of building surfaces is more about constructing imagery through its visual appeal that entails layers of intricate marks in graphite. At places, she builds boxes of light greys and blacks in her work, so a viewer is entangled into the depth of these spaces. Along with these pieces, some graphite on papers is also created on the basis of a grid. These works by Meher Afroz refer to an artist’s life story (hence the title of the exhibition Aap Beeti), but narrated in such a scheme that the personal history turns into a common story, which is more about material, medium and manner of making, all that takes one away from specific to general and universal.

It is about her own autobiography as well as the life stories of all those who love the touch of a pencil and brush on paper and canvas, and compose tones and shades to create sensitive surfaces. As Jose Saramago describes his compatriot Fernando Pessoa, a person who spent his years in arranging words with each other.