Sialvis in the perspective of history

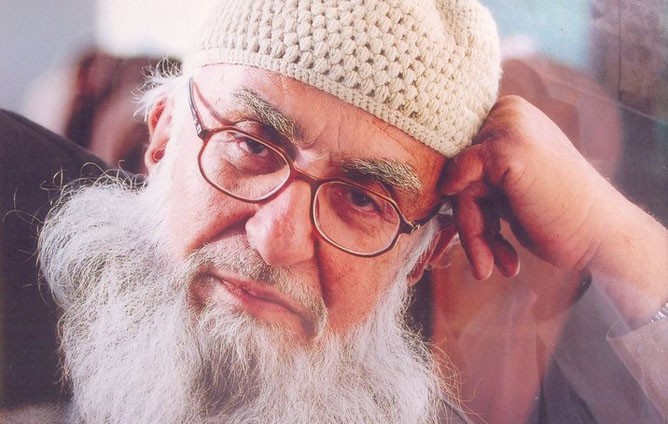

In the last few days, the media spotlight has shifted from Khadim Hussain Rizvi to Hameedud Din Sialvi, sajjada nashin of Sial Sharif. Pir Hameedud Din Sialvi has taken on Punjab’s law minister Rana Sanaullah for his equivocation regarding Khatm-i-Nabuwwat (finality of Prophethood). The limelight that Hameedud Din Sialvi has invited warrants a full-fledged column on the shrine of Sial Sharif and the various sajjada nashins who had ensconced on the Gaddi from Shams-ud-Din Sialvi onwards.

Sial Sharif is the most revered shrine of Chishtiyya Sufi order in district Sargodha. In British India, Pirs of Sial Sharif were visibly tilted towards religious puritanism, thereby moving quite close to the ideas of the Deobandi creed. The sajjada nashin of Sial Sharif’s condemnation of Ahmadis and damnation of Shias marked repudiation from the established inclusive discourse of Chishtiyya silsila. The shrine in Sial Sharif is surrounded by Shia Sufis’ shrines at Shah Jewana and Rajoa Saddat in Jhang district, which wielded considerable spiritual and political influence in the region.

Because of these, the sajjada nashins of Sial Sharif espoused ideas and practices of religious exclusion. Sectarianism was reinforced and, after independence, Sial Sharif has drawn closer to the extremist Sunni sectarian organisation, Sipah-i-Sahaba Pakistan.

Generally, Chishtiyya Sufis such as Moeenud Din Chishti Ajmeeri, Khawaja Qutb-ud-Din Bakhtiyar Kaki, Sheikh Farid-ud-Din Ganj Shakar and Sheikh Nizam-ud-Din Auliya subscribed to inclusive and syncretic religious tradition, making that order popular among all shades of religious communities. The silsila attained its zenith in fourteenth-century Delhi with the rise of Nizam-ud-Din Auliya.

In the Punjab, however, Chishtiyya teaching acquired the momentum of an organised mystic movement through striving and karamaat of Sheikh Farid-ud-Gin Ganj Shakar. The force of his charisma and elevation of Pakpattan to the silsala’s epicentre attracted people from all corners of India. With Farid’s demise in 1265, Nizam-ud-Din Auliya became its principal protagonist. After Nizam-ud-Din Auliya, Chishti influence in the Punjab suffered an apparent decline until the eighteenth century.

Throughout these centuries, the Punjab witnessed the waxing influence of the Qadiriyya and Suharwardiyya orders. The resurgence of the Chishtiyya silsila in the region is coterminous with the decline of the Mughal Empire in the region, emergence of Sikh Kingdom and the arrival of British from the late 18th century onwards.

In the resurgent Chishtiyya order, the emphasis was on the strict following of the sharia and reestablishment of the Muslim political rule, either by reviving religious practices among Muslims or jihad. In the 18th and 19th century South Asia, Sufis’ involvement in politics and war, and in influencing the social and cultural practices based on the sharia, significantly redefined relations among different Muslim communities. One such relationship was between the Sunni and Shia communities.

Read the first part: Religious modernism and Barelvi creed

Importantly enough, Chishtiyya revival came about in the Punjab through Noor Muhammad Muharvi (1730-91), who established a khanqa in a small town of Muhar near Bahawalpur. The Chishtiyya revitalisation subsequently reached its culmination in Taunsa, Golra, and Sial Sharif. Muharvi’s teachings accorded primacy to "ethical ideals and standards of Islam" in the code of conduct and rules of behaviour. Thus, Muharvi’s teachings reconciled Sufis with the ulema by preferring devotional Islam over literal and professed strict adherence to the Sharia as a prerequisite for entering the fold of the Tariqa. This neo-Sufi pattern was followed by Muharvi’s successors such as Salman Taunsvi (1770-1850) and Shams-ud-Din Sialvi (1799-1883).

Here it would not be out of place to mention Barbara Metcalf’s assessment of the 19th century Punjab where religious consciousness increased among the ulema as well as Chishtiyya, Nizamiyah Sheikhs, and later came to be known for the teaching of Islamic law that was the specialty of only Deoband. Thus, not only the literalist version of Islam came into vogue, emphasis on scripture found acceptance.

It was this context in which Shams-ud-Din Sialvi, Muharvi’s illustrious successor and the spiritual preceptor of Shah Salman Taunsvi established his khanqa in Sial Sharif, and directed Muslims "to cling tenaciously to the path of the Shariat, and reform their manners and morals". He also exhorted the Muslims to rescind practices such as Samaa (Qawwali) with music and Chilla Kashi (40-day spiritual penance) which were presumed to be in violation of the edicts of sharia.

Read the second part: Religious modernism and Barelvi creed II

All said and done, the practices rooted in the composite culture of the Punjab, which have been flapped throughout the medieval age as the distinctive feature of the Chishtis, were being purged as un-Islamic. Puritanical tendencies, therefore, crept into the Chishti inner core in the early 20th century and rural Punjab was profoundly affected by these reformist ideas. The reformatory streak proceeded to gain further strength among Shams-ud-Din’s successors; Zia-ud-Din Sialvi, the grandson of Shams-ud-Din, was also a staunch follower of the sharia, and this clearly resonated in the organisation of Khanqa-i-Nizamiyah under him.

Such tendencies made an indelible impression on the spiritual leadership of popular Islam, too, which was demonstrated in the establishment of Dar-ul-Uloom Naumaniya in 1887 in Lahore. Later on, in 1920, another institution, Dar-ul-Uloom Hizb-ul-Ahnaf was founded in Lahore which "tied the development of Ahl-i-Sunnat Wal Jammat perspective to a similar perspective being developed by Ahmed Raza Khan Barelvi." Emulating the same pattern, Sialvis also established Dar-ul-Uloom Zia Shams-ul-Islam [Sial Sharif] in the early decades of the 20th century. It was set up along modern lines and the instruction provided there was sharia-oriented. Ulema were invited to instruct students in Hadith, Fiqh and logic. Zia-ud-Din’s efforts to bridge the gap by organising lectures and meeting there significantly shaped the ideas of his successor and particularly his son Qamar-ud-Din Sialvi (1906-1981).

To be continued