Film hoardings and billboards were a much sought after publicity campaign, known to the filmwallahs, till digital technology and flexes took over, leaving the poor, self-trained artists out of work

The decline of Lollywood, a term used strictly for the Lahore-based film industry, over the years, put many people associated with it out of work. These include, among others, the poor and mostly illiterate men who earned from painting the huge film hoardings to be displayed on the cinema houses.

Traditionally, these hoardings were the reason why the common people would be attracted to a film that was showing at a theatre or due out. These ‘paintings’ were often also placed behind the tongas and rickshaws as part of the publicity campaigns.

The audience turnout at the box office depended also on how delightfully attractive -- not to mention, laborious -- artwork employed by these men who were skilled professionals.

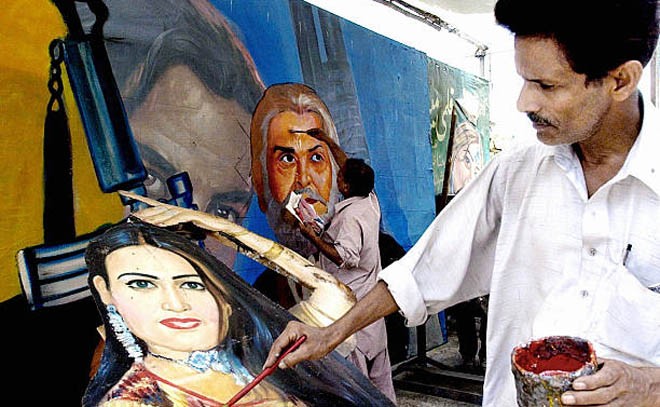

Painting the film hoardings was a common practice -- till the early 2000s, when the art gave way to digital technology and flexes. The ability to capture the essence of a movie, apart from creating exact replicas of the actors, was tough. Everything, from the tedious sketching of the outline to the delicate strokes of paintbrush on the canvas, was like breathing life into a lifeless picture. It was an art that required keen and talented individuals.

For the painters of film hoardings, it was more of a passion than a means to earning bread and butter. They were highly sought after people. However, the introduction of new technologies and lack of relevant policy framework on the part of the government pushed these artists into oblivion.

Royal Park, near Lakshmi Chowk, was the hub of Pakistan’s film business in the region. There was a time when it was considered among the biggest film markets in South Asia. Its history dates back to the pre-partition times when luminaries like B R Chopra and Dev Anand walked the streets of the same market.

Munir, a middle-aged man who has been working in the market for over 40 years, recalls the time when there were about ten different shops that had at least eight to ten painters ready to work. He was not an artist but he was witness to so many eminent film personalities of the time visiting the place. The main attraction was the many film hoardings and billboards adorning the place. "There were a large number of cinemas, close to Royal Park, which required the expertise of painters of these hoardings on a regular basis," he tells TNS. "And there were about a hundred individuals who were regularly employed for the

It was a lengthy process. The artists usually had to work on 20-40 feet high billboards that they would divide into different sections, initially with lines and later they would start sketching. The sketching would be done in a way that they could work on one section at a time before they put it all together, to be colour-painted later on.

This was not the only attention to detail that was expected of them. The way a movie protagonist and anti-hero were painted was dependent on how they were positioned in the film. Their expressions, facial features, continuity, all of it had to be perfect for the billboard/hoarding to attract large audiences to the movie.

With the advent of digital printing and flexes, the Royal Park painters began to lose their importance. The new technology meant that the film producers could save more of both their time and money. The cost-effectiveness of these modern practices led to the substitution of man with machine. Regardless of the contribution of these artists in the movie business, their skills and recognition were lost in translation.

Artists are given great value around the globe. Enthusiasts would be ready to pay hefty amounts on a renowned painter’s work to be hung on their home walls. Artists spend years perfecting their brushstrokes in order to create a brand for their name. What is worth mentioning is that the painters of Royal Park, despite lacking any formal training or diploma, were just as perfect in their work as any other artist.

The ability to paint a billboard picture was a family heirloom that was proudly passed down from one generation to another. Their fathers, who were trained by theirs, trained majority of these artists. There are not many left in the business now. Ustaad Ajmal, Ustaad Arif and Sarfraz Iqbal are the only ones who are still part of this dying art. Sarfraz Iqbal (aka S. Iqbal) has stayed in the industry because of his contributions, starting from the early 1970s till his most recent work on the poster of Zinda Bhaag. Ustaad Ajmal and Ustaad Arif have stuck around because they were able to gain some form of formal training and now make a livelihood by selling paintings commercially.

The question that arises here is: what happened to the rest? Unfortunately, their current occupations are not even remotely relevant to those of an artist. Some are driving rickshaws, painting houses, working as a cleaning staff at a hotel, school, or a restaurant, or not working at all.

Advancements in technology are inevitable. Science will continue to innovate and make our lives simpler by inventing machines that reduce human effort by a large margin. People will continue to lose jobs as time passes by. However, with practical support from the government, and with the right policies introduced, the skills of out-of-work artists can certainly be put to better use. Sadly, our artists from the Royal Park market have received no help at all.

Theatres are still operational in Pakistan, which require set designing quite often. A part of a proposed rehabilitation programme for these artists could have been to reallocate them to these theatres where they could continue with their artistry. Sections of the government responsible for the restoration or preservation of culture could have organised festivals for these artists to showcase their skills. Welfare programmes could have been devised from tax revenues, if there were any, for these disengaged from the workforce. Even movie producers themselves could have come up with ways to still put these maestros to work. They certainly have the experience for that.

Unemployment, of any type, has consequences to the economy. Little efforts can go a long way, but people seem reluctant to take the first step. If nothing was to be done about this dying art it will only be remembered in the annals of film history in Pakistan.