Haruki Murakami’s latest anthology of short stories explores various facets of love… and life

The title gives a fair guess of what lies within. When you pick up Haruki Murakami’s compilation of short stories -- Men Without Women (2014, now translated into English) -- you expect lovelorn tales, tales of heartache and heartbreak and some fine pieces of prose.

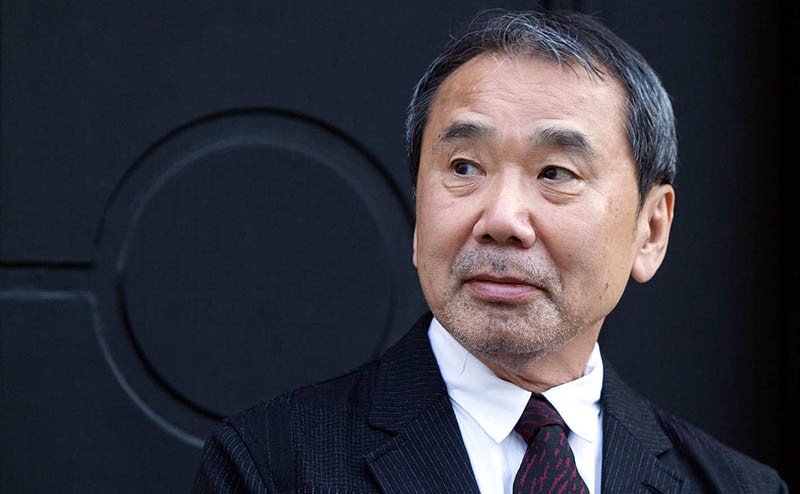

Men Without Women is all that, and more. It does not disappoint on the scores mentioned above, certainly. Murakami has been translated into 50 languages, and is globally acclaimed among writers of postmodern literature. There is finesse in his storytelling, and delicacy; at times he surprises by interjecting a word or two of starkly crude slang. There are stories about life, about different lives, of pubescent sexuality, and of coming-of-age -- at different ages. There is also sadness, there is poignancy and there is darkness.

Through all the stories, there is the running thread of overlapping fantastical realms with worlds of reality. As Scherezade’s storytelling is described in the titular story, "reality and supposition, observation and pure fancy seemed jumbled together in her narratives," so too does one surmise the experience of this tryst with Murakami. But then, Murakami is a writer who is loved for his magic realism, and this may well be how he describes himself too. In his twilight zone, beautiful thoughts such as, "Dreams are the kind of things you can -- when you need to -- borrow and lend out", slip in seamlessly. But stay with you for a long time.

What else are Murakami hallmarks? You cannot read a Murakami work without adding to your knowledge of music. Like him, some of his characters in Men Without Women have a penchant for playing music. The man who runs a bar, Kino, plays Coleman Hawkins, Billie Holiday, Teddy Wilson. Kafuku, the actor who inhabits the story ‘Drive my Car’ listens to Beethoven, or the Beach Boys, the Rascals or the Temptations. And then there are the cats. In this anthology, there is a docile grey cat in one narrative. Murakami’s cat is not black, it is not malevolent; that there is a chilling air to the story, Kino, in which the cat appears and then disappears in a bar, among other mysterious happenings, simply leaves one wondering. You are led into worlds and then left wandering. In actual life, Murakami, together with his wife, once managed a coffee house and jazz bar in Tokyo, called Peter Cat, from 1974 to 1977. Ah yes, there’s the cat again…

The author has, in fact, been quoted on the integration of the abovementioned into his literary world -- music, and cats -- as saying "I collect records. And cats. Whenever I write a novel, music just sort of naturally slips in (much like cats do, I suppose)."

The brevity of this collection -- seven short stories in all -- adds its own flavour. These are effective, powerful words, loaded with meaning, carefully chosen and carefully crafted. You are left with images. Something as mundane as the skill of a good driver is described in a lyrical way. "When he closed his own eyes, though, he found it next to impossible to tell when she shifted. Only the sound of the engine let him know which gear the car was in. The touch of her foot on the brake and accelerator pedals was light and careful. Best of all, she was entirely relaxed. In fact, she seemed more at ease when driving." Thus Kafuku describes Misaki in ‘Drive my Car’.

‘An Independent Organ’ and ‘Drive my Car’ are stories that carry the maximum intensity of love, or, of men without women. They are imbued with passion, pain, and longing. And with basic human emotions. "I worried that I might lose her. Just imagining that made my heart ache." And lose his wife Kafuku does; first to infidelity, and then to death. "In the end, though, I lost her. Gradually, in the beginning, then completely. Like something that is eroded bit by bit. The process began slowly until finally a tidal wave swept it all away, the roots and everything…"

Dr Tokai, the main protagonist in ‘An Independent Organ’ falls in love, and, for the worldly womaniser that he is, is overwhelmed by an intensity that is beyond his comprehension and control. In a world that is unknown to him, Tokai ends up on a destructive path. Is there a lesson therein, about infidelity? Perhaps. The doctor dwells on his helplessness as he reveals his emotions to a friend, "I couldn’t come up with many negative things about her. And there’s the fact that I find even those negative qualities attractive. And another thing is I can’t tell myself what’s too much for me, and what isn’t. This is the first time in my life I’ve had these kind of senseless feelings."

Yet, the ultimate ode to love lies in the story ‘Men Without Women’ itself. Dotted with sparkling little gems, there is a passion in his words when Murakami says, "It’s quite easy to become Men Without Women. You love a woman deeply, and then she goes off somewhere." Or, "You are a pastel-coloured Persian carpet, and loneliness is a Bordeaux wine stain that won’t come out."

Murakami paints a surrealistic canvas. In his tale a willow tree can become…whatever you want it to be. Love can take on sinister overtones. A seemingly simply told story of an ordinary relationship can have profound melancholy undercurrents. The love he writes about is more often than not steeped in ugliness, instead of beauty. As he deconstructs his story in layers, ordinary folks come to life in shades of grey. You could find yourself empathising with the darkest character in a narrative, or wondering about thoughts left unsaid.

Nonetheless, when he chooses to paint love in bright hues, he does so beautifully, and yet also at times in cliché, making a mockery of the fact that he is, after all, writing about the emotion that is often best left to clichés. "It feels like our hearts have become intertwined. Like when she feels something, my heart moves in tandem. Like we’re two boats tied together with rope…If my feelings for her get even stronger, what in the world’s going to happen to me?" There is a sense of wonder in these words, of celebrating love, yet there is a question mark.

Somewhat baffling is the fact that Murakami gave his book the same title as Hemingway’s Men Without Women -- also a book of short stories published in 1927. Why? My guess is as good as yours. To compare the two would be to start off another debate entirely, but is that what the author sought? Perhaps, in the author’s words…"But, Mr Kafuku, can any of us perfectly understand another person?"