Life is a series of happy and unhappy accidents and the best ones are buying and reading used books. Books that we buy at cheap rates always make us richer

The first book I ever read was stolen/borrowed from the shelf of an old retiring uncle who was moving to the country. Clearly, he did not need the book as his bags seemed packed and there seemed to be too many books on the shelf for him to have forgotten them all.

It was a copy of Agatha Christie’s By the Pricking of My Thumbs. I was 9 or 10 and had no idea what I was about to read. The book was thick, old and so impressive. I retained the memory -- the book cover held a hung painting, with trails of blood drizzling from the wall behind it. The painting displayed a house beside a flowing stream with a bridge over it. There were rows of trees on the other side of the wooden footbridge, and a clear blue sky in the background. The cover intrigued me despite the blood. The back cover had its upper left corner chipped and the book looked very used -- it had many dog-eared pages, several folds along its crooked spine and a certain looseness that comes from repeated page turning.

The pages, yellowed with time, had acquired that most sensuous scent of old, used books. I used to turn them and sniff them like an addict every now and then. I read that book many times, and the story changed as I grew older. However, right from the beginning, I felt that I was holding something very deep and meaningful -- a precious thing. It was too overwhelming a sentiment to put to words at that age.

Inside the book, on the first page, there was an inscription on the upper right corner in black. "…Something wicked this way comes…" and then my uncle’s name "- A. Karim". He’s a poet. He writes rhymes. I thought. But more interesting was the next page after a turn. "To Sally, with all our memories of childhood and adventure, with the love for crime, and the more heated love that I grow for you, every day. Yours ever, Bill". Every time I read the book, Christie’s Tommy and Tuppence came more alive for me but I struggled, every single time, with the mysterious Sally and Bill. I could never know anything more about them, except that Sally seemed to be a really fun person and that Bill was crazy about her. This little detail made me imagine so many Sallys and Bills that it became hilarious. They were English, I presumed, and that made me want to reach out to anyone from England. That’s the best part of childhood -- we are not aware of the alternatives to belief.

And as if the universe was conspiring -- almost hatching a plan to prolong my childhood -- I came across an advertisement in the young reader’s page of the newspaper from a certain Amy Turner, age 12, living near Hamsey Green, London, who was looking for a "Suitably-aged Indian pen-friend". I wrote to Amy immediately and without wasting much time, in my second letter I asked if she knew a couple called Sally and Bill. Amy replied that though she had a second cousin in Cornwall called Bill, she didn’t know if he had a friend called Sally. I persisted, of course, and I am sure she figured out soon enough that I was a creep. Our correspondence dwindled when I came to know that her second cousin was merely 13-years-old and couldn’t be the Bill I was looking for.

As the more real issues of school grades, homework and such made themselves urgent, my obsession with Sally and Bill began to fade. By the time I remembered them again, I realised the probability of ever finding them was almost null.

Also, something else caught my attention: a few years later we were to perform a play at school based on Macbeth and I realised my uncle was no poet, but William Shakespeare was. I like to believe that this had something to do with the fact that Macbeth is my most beloved text to date, and that the first role I aspired to act on stage was that of Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth.

The flow of cause and effect in life is mostly unpredictable -- we don’t really know how the things we do or don’t cause big alterations in ours and others’ lives. Life is a series of happy and unhappy accidents and the best ones, I think, are buying and reading used books. Though we buy used books at cheap rates, they always make us richer. Not only do we buy what the author-publisher intended us to read, but we get to read so much more: Notes, anecdotes, explanations, messages, inscriptions -- so many more stories, so many subplots, so many lives scribbled on pages used, read and lived by so many people.

I do not know how I would have completed an English Literature degree without coming across all the old, used books I bought at second-hand bookstores in different cities I’ve lived in. For example there is my ‘annotated Yeats’ (as I call it), which I bought from College Street in Calcutta. It once belonged to another literature student who almost used the collection as her (his?) notebook, and in the notes, almost argued with herself as she struggled with Yeats’ philosophy in his poems. There was even a sketch of the "widening gyre", unravelling for me the trajectory of the first lines:

Turning and turning in the

widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the

falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre

cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon

the world,

A few lines later, she had underlined the phrase "A shape with lion body and the head of a man" and scribbled "pg. 53" in the margins. That was the page where ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ began. She wrote, in a small, cursive, hurried hand, with dripping blue ink, how "The figure of the gyre is a repeated occurrence in Yeats’s world and once we have understood the workings of the gyre, we could, if we tried, understand the workings of our own perverted hearts and minds that constantly harbour an animosity for each other, forever in confidence, forever in conflict". This book for which I had paid Rs25 became my Bible and I carried it everywhere. Yeats became my god and the previous owner of this book, my prophet.

She had missed out on vital information though - nowhere had she written her or any other name. As if she always knew, that not books, but their contents belong to the reader. Even now, every time I think of how she must have slept with the book beside her or read it in a crowded bus or flipped through it while waiting for her friends at a dhaba, scribbling her thoughts onto these pages, a shiver runs down my spine. Why and how did this book find me?

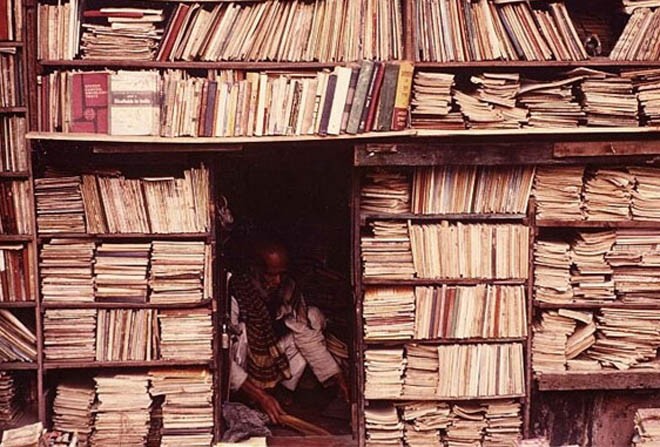

College Street Calcutta is one of the more bizarre of markets in the world. There, you can be rich even with a tiny amount of cash. All you need is time to while away, patience to turn pages, an eye for strangely damaged covers and the knack for chatting with old lanky men who seem to know nothing about the world except for books. These seemingly random men are a strange collective of the most well-read men I have known, surviving on loaned tobacco, gifts of small packets of spiced puffed-rice with mustard oil and years and years of reading old and used books. "And hwat do you want today, young sistar? Some Blake or Baairon? Or Emilee Dickinson paarhaps? See, I habe a thaard-hand kaalekshan. Give me 35," he said, and handed me The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. This collection was previously owned by one William Dunhill and then later by Radha Madhav Gupta, who identified herself as "Second Year, Scottish Church College, Calcutta", and who thought "Miss Bishop was way ahead of her times, solitude and truth her only companions in life and poetry, living a most painful, passionate life". In this way, I acquired used versions of Hamlet, Metamorphosis and The Great Gatsby, the last one belonged to a mysterious C. K. Later.

When I moved to Delhi, I frequented the Sunday second-hand book bazaar in the Old Delhi neighbourhood of Daryaganj. There I paid the same price for used copies of the Magna Carta and Sputnik Sweetheart, owned by a certain Samuel Webb and Anonymous, respectively.

A very strange incident tied me to the second-hand book bazaar in Lahore. I was approached by a Bangladeshi academic, Professor Lubna Maryam, who had recently discovered that her grandmother Rahat Ara Begum used to write fiction in Urdu and had even translated some of Chekhov’s Russian stories into Urdu. In order to restore her grandmother’s works, she had to first collect them. She asked if I could find old collections of Rahat Ara’s stories, that seemed to have been published by the erstwhile Taj Publications in Lahore.

I found that the publishing house closed years ago. I asked my friend who asked his friend who found a tattered copy of her collection of Ghunchhe Afsane, almost falling apart but the contents were intact. It had no name and one can’t say who owned the copy and what series of events caused this almost extinct book to finally reach the hands of Maryam Apa, currently living in Dhaka.

Second-hand book markets say so much about the city and the reading public inhabiting it. The market is almost a mirror to people’s choice of life and literature. In a world that is quickly shifting values to temporary success and pleasure, the market for old and used books is a symbolic struggle to hold onto a deeper, meaningful sense of value. I think second-hand book markets add a different dimension to debates between buying real books and buying e-books or Kindle versions. There are online associations that circulate used books but the joy of finding someone through a shared reading of books is unparalleled.

I fell in love with a man who sent me some of his books before we had ever met. His books are all I have now, the bookshelf has become a monument of love. A glance at one’s bookshelf is like a film playing, of one’s own life.

Books that belong to people we do not know, books that have tied our lives together at the crossings of old markets and lined hands of old booksellers, the reading of certain books as the only way in which our lives are connected. Books from friends, lovers, teachers, in different places and phases of life, books that have been touched by them, that still smell of who they once used to be, books that still hold their handwritings, in flowing English, flowery Bangla, drifting Urdu, scattered Hindi, illegible Punjabi, scrawny French, stern German. Books that we bought together, books that we stole from each other, books that we used as excuses to meet for an unplanned rendezvous. Books that encase time and memory in the form of dried flowers between pages, books that are leftovers of all the lives that touched us, books that belong to people who are no more with us, just like incomplete collections whose missing volumes grace the shelves of others with whom we have parted long ago. The books of others, carrying messages in a loop, year after year, decade after decade, across the linearity of time, as books are supposed to.

Twenty years later, I know what was so precious that I was holding in my hands as I picked up my uncle’s By the Pricking of My Thumbs. I am tempted to write ‘time’, but it was heavier than that. It was a willingness to believe, in a shared sense of time. Buying, reading and giving away/selling used books are all acts of faith, one way or the other. And whatever adulthood may have managed to do, it has not yet successfully nullified the possibility that as I leaf through the innumerable books sold at second-hand prices under Waterloo Bridge on the banks of the Thames, I might yet come across a used copy of Agatha Christie, that Sally had gifted Bill to reciprocate his enthusiasm, love and hope.