As years rolled by, two revolutionary friends Faiz and Khurshid Anwar had a different trajectory regarding aligning action with words or note

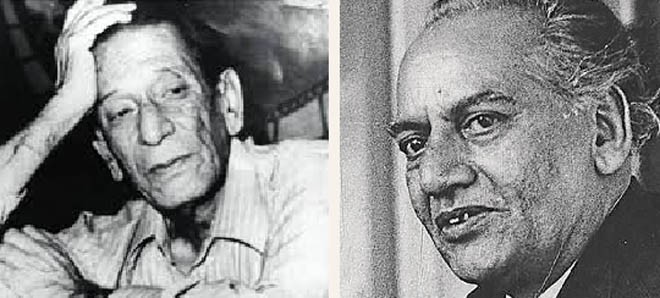

Khurshid Anwar and Faiz Ahmed Faiz were friends. They were in college together and their friendship lasted their life time. So much so that they also died within days of each other.

In the 1930s, when the two met in Government College Lahore, the air was abuzz with the fervour of getting rid of the colonial yoke. The nationalist movements were widespread and popular, and had many strains to it -- the latest that had added its hue then was of Marxism. The aligning of ending exploitation of colonial rule and all other types of exploitation must have been an irresistible ideal to pursue.

It appears from the record and conversations with those more familiar with the times that Khurshid Anwar was more into aligning action with words or the note. He appeared to be more active and took part in politics which was more action-oriented, compared to Faiz who seemed to be more preoccupied with the magic of the spoken and the written word.

It is difficult to say how Khurshid Anwar from a family of non-musicians got so immersed in music. It could be that his father was a connoisseur of music and held sessions in his house which obviously exposed the young Khurshid Anwar to music of the highest quality in his impressionistic years. Lahore, at that time, had some of the most outstanding vocalists and instrumentalists of the subcontinent. And it was in those times that he was made the shagird of Ustad Tawwakal Hussain Khan, a virtuoso and a no nonsense type ustad. He started to be taught music in the most conventional manner, that is through the ustad shagird personalised nexus which had been the proven time-tested system of transmitting music knowledge from one generation to the next.

Faiz was writing poetry and new experiments fascinated young poets. N. M Rashed was seen as very promising and given plenty of space by the editor of the Ravi, Agha Abdul Hameed. Faiz followed suit as if together heralding the new era of Urdu poetry in this region. But Khurshid Anwar got involved in politics outside the college campus and was fascinated by activism and armed struggled of many youngsters that espoused what was best represented by the charismatic personality of Bhagat Singh.

It was in one of the severe crackdowns on the group that he was also arrested and tasted prison, charged with armed rebellion very early in life. Though he was acquitted in the popularly known Picric Acid Case, the traumatic happening did have a telling effect on him and in some fundamental way changed his life. Faiz wrote poetry and was not so drawn to the armed and militant activities of freedom struggle then. He made a name for himself gradually among the ranks of the poets of his times, and grew more conscious of the inequalities and injustices embedded in the system as he graduated and went out into the big bad world to sustain his body and soul.

Realising the changes that had taken place, and the need of involving the common listener in music, drove Khurshid Anwar to initially join the radio and then the films. There, his struggle must have been to retain the excellence of music while refraining from bowing low to popular taste. Instead of bringing down the level of music, he must have wanted to raise the level of the listener, a task that has rarely been achieved by even the most passionately ardent and committed of humans in pursuit of bridging the great divide of class and with it of its cultural variations.

As the years rolled by, the onset of the war and subsequent partitioning of the subcontinent into two independent countries, it appeared that Faiz ironically got more involved in the active side of politics while Khurshid Anwar receded from it to be more engulfed in the battle of the cultural divide that he was facing or had come to realise that it mattered more. With Faiz joining journalism, it was apparent that he was thrust, as if just behind the frontline of politics in the country. He was not able to avoid it much longer and was to be imprisoned in 1951, for a much longer period on charges that were similar to that of Khurshid Anwar levied a decade and a half earlier. It must have been sedition, rebellion, treason, armed attack against the functionaries of the state, inciting violence and garnering help from enemy countries. The list of the charges, a holdover from the colonial era, has continued to be imposed on those wanting a country different from what it became over the decades.

When Faiz asked Khurshid Anwar to do something about music in a much later phase, during the 1970s, the latter proposed the recordings of the thaats/raags with some basic information about the gharanas accompanied by succinct comments and to initiate a programme for the acquisition of musical knowledge in the most traditional of manners -- the way he had acquired it himself decades ago through the ustad shagird nexus. Of the entire package called Ahang-e Khusravi, the first proposal he was able to execute but the second could not be implemented for whatever reason.

Times had changed so the old methods had to be incorporated in the then current times. The same dilemma he must have faced, that of accommodating the most effective system of a personalised transfer to times which had moved on to a more impersonalised transfer of music knowledge. He was again out to balance the virtues of the past with the demands of the present, the same which Faiz was also wanting to achieve by incorporating the stylised lyricism of the traditional poetry for themes that were very different like that of freedoms and equality. Many felt that the poetry demanded a new idiom but Faiz did not see any contradiction between the two.