Dr Mahmood Nasir Malik’s poetry deals with nature, the changing forms of seasons and evenings

It’s difficult to imagine full-time poets. Around us, the luckier poets are professional teachers who steal time from classes to write poetry. But here is a man who typically embodies a future poet in an environment of receding government jobs and pension benefits and with little leisure time at hand. Dr Mahmood Nasir Malik is an accomplished physician, having retired as Professor of Medicine from Allama Iqbal Medical College Lahore and currently serving as Professor and Dean of Medicine in a private medical college.

For Dr Malik, time has a special value. He has completed many a ghazal and nazm on the way from Nishtar Hospital Multan to his hostel or while travelling between hospital and home. Once, he composed a poem on his way to Pakistan Television’s Lahore Centre where he was to record the very poem he just composed.

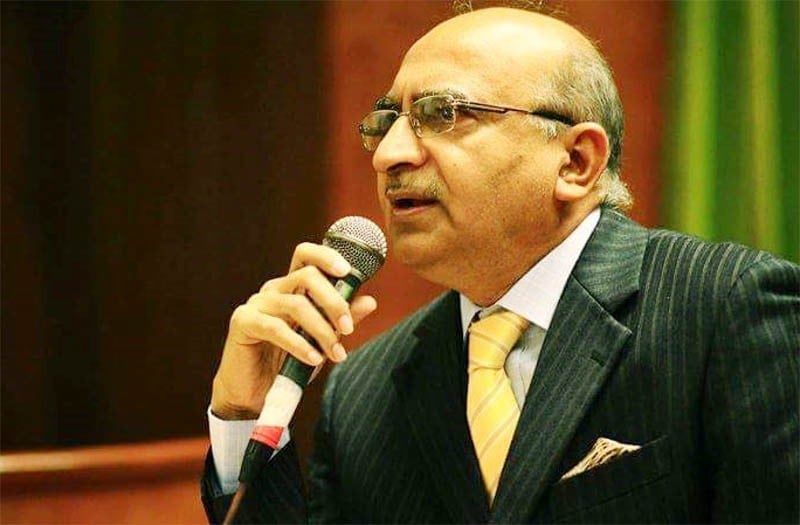

At 60, Dr Malik is a striking figure with pointed eyes wrapped in gentle glasses. The precision that is typically seen in physicians can be felt in his words when he talks about poetry. He is a man who remains attentive while having a conversation; disjointed phrases are rare. His memory is remarkable. One wonders how vividly he remembers dates and names, interspersed with lines from his own and others’ poetry.

When I meet him in his clinic on a Friday afternoon, he tells me it’s important to find time in our busy schedules. "Now I realise there is a state of mind that overpowers me. I do it in a go. I read out a new composition to a friend. I ventilate and it’s done. I don’t rework."

The concept of time in his poetry, however, is in contrast with the schedule of the poet. It’s subtle, serene and captures the complicated motions of things without being hallucinatory. His poetry deals with nature, the changing forms of seasons and evenings, rains, birds particularly sparrows, trees and rivers set in an imagery of green pastures. Some hills too and a lot of sadness.

His poetry touches you for its visual imagery. When I ask him why this tendency to capture images, he says this is how he perceives the world. He attributes this to his rural background, the imagery of his village Birbal Shareef on River Chenab near Shahpur, district Sargodha. In its horizon, lie mountains that hide the village Nulli in Soon valley, the valley from where his father came. He lost his father when he was only 6-months of age and this loss perhaps spreads in many directions in his poems.

Dr Malik lived in the village of his maternal grandparents. "There were two mulberry trees in our home, one was later cut, where sparrows would incessantly chirp during early mornings and evenings around maghrib time. As a child, I wondered what they talked about. What they were doing and saying? Why were they making the noise? Sometimes they would all suddenly break and start this chorus again.

"I noticed that some sparrows died after heavy rains or storms. Once, all the chicks of one of our hens died. She went under the tree where they died, stopped eating and we had to carry her back to her cage every day. Then I realised there is sense of loss in animals too. She was depressed.

"I internalised that environment, especially the evenings. I have a deep sense of sadness and amazement but I don’t conceive it in words or a statement. I imagine poetry in images, subtle images. That is why I put distances between couplets. There is link between couplets but also distance."

Shakil Adilzada, renowned writer and editor, wrote in his first book, Dhoop Hai Mairay Dil ka Mausam (1991), that he was touched by the sadness in Dr Malik’s poetry. He wrote: "Mourning the loss of a person then searching for him, is the asset of this poetry…If a poet makes you that anxious then he must have been tested by times in multiple ways".

Dr Mahmood Nasir Malik was fond of painting and calligraphy in childhood. He would draw sketches on his copy of Fanoon-e-Amli (then a sketchbook of sorts). His teacher Khalil Farooqi made tughras (calligraphic monograms). Dr Malik started copying that art and developed his own writing style in reverse.

When he became the editor of his college magazine Nishtar, he joined the team of Sadequain for filling his paintings in the main branch of the National Bank on Mall Road. He got this opportunity through a friend, Syed Saleem Zia. After a week’s work, he requested Sadequain to design the title and draw sub-sections of Nishtar. Sadequain willingly agreed. He was twice selected as the editor of Nishtar Medical College’s magazine including its silver jubilee edition. Fifty copies with resistance literature were published separately from the edition that went public. In that limited edition, there were pieces from progressive writers in Multan like Samee Ahuja, Asghar Nadeem Syed, Rasheed uz Zaman and Dr Anwar Ahmad. He says that it was Zia era and "publishing such stuff was risky".

Having topped in the middle school exam in Sargodha district, he had two options: either to study in Sargodha or Lahore. Since his brothers had already come to Lahore, he followed them and was admitted first to Central Model School in 1970 and then Government College Lahore (GC) in 1972. These were charged times when people were experimenting with new ideas in politics and literature, both.

Government College Lahore groomed him well. He was a self-styled founder and organiser of the Young Writers Guild. Unfortunately, the Guild did not survive for too long. Dr Malik, however, absorbed himself in other literary activities.

He studied a lot of Russian and French fiction translated in Urdu. Looking at his reading habits, one day the college librarian asked him: "Don’t you have to prepare for your FSc exams?" He remembers a story about how his brothers had to once search for him because he lost track of time while attending session of Halqa Arbab-e-Zouq.

According to Dr Malik, it was at Majlis-e-Iqbal at the Government College that he learnt what poetry was.

Siraj Muneer, a writer who Dr Malik met during these times, thought he had in him a great poet and encouraged him. By this time, Dr Malik also started contributing a column on the literary activities of the college, entitled "Ravi Diyan Chhallan" (Tides of Ravi) in the literary page of the daily Musawat. The editor of that page was the famous film reporter Zahid Akasi. Along with fellow GC student, Amin Ul Hasnat Shah, now an MNA and federal minister, he also joined daily Wafaq as co-editor of its student page. It was in these times that he became well versed with Arooz (prosody) through his cousin Najam Hussain who studied in the Oriental College.

"Those were wonderful times. It was a great learning experience. People had authority over their respective fields and would instruct juniors," recalls Dr Malik.

However, it was at the Nishtar Medical College Multan that he found freedom from the bounds of home, he learnt how to live on his own, and found his poetic expression. Shamoon Saleem, Shahid Mubashir, Ibrar Ahmad and Nasir Saleem were his contemporaries. Then Azhar Ali and Muhammad Ayub joined. All these medical students earned a reasonable name in the poetry scene.

Dr Mahmood Nasir Malik thinks that this creative and intellectual environment was largely owed to stalwarts of progressive movement who ran the Multan Academy, i.e. Dr Anwar Ahmad, Muhammad Amin, A.B. Ashraf, Asghar Nadeem Syed, Arshad Multani and others. Their encouragement brought many medical students to the literary world.

Dr Mahmood Nasir Malik says he burnt all his poetry in the final year of the college after listening to a poem of Musadiq Iqbal, better known as Musadiq Sanwal. "A friend got suspicious about what I was doing in the locked room and kept knocking on my door, but I did not open it until all my poems were burnt. I felt my poetry was worthless. That evening, however I composed a ghazal that contained the radeef, (repeating end words of second line in each couplet) duhkh."

The rationale to publish his poetry came from Fida Hussain Gaadi, a Seraiki intellectual, who told him that not everyone could do poetry as well as Ghalib. Before hearing this, Dr Malik was adamant about not publishing his work. Thus came Dhoop Hai Meray Dil Ka Mausam.

Urdu and Punjabi poet Munir Niazi appreciated his poetry and commented in writing: "I love the poetry of Mahmood Nasir Malik because it absorbs beauty along with dreams and ideas. I find freshness and uniqueness in his poetry. He writes ghazals in short metres impressively and his poems sound like unheard stories". These were huge compliments.

Novelist and translator Dr Arshad Waheed, another fellow student from Nishtar Medical College, views that the striking feature of Dr Malik’s poetry is his primary relationship with nature. "It is grounded in his childhood in the 1970s and the rural/peri-urban experiences. It is about scenes and environment that are fading away now. There were many creative writers and poets who expressed themselves in Zia’s era."

This year, after a gap of 26 years, Dr Malik has published his second collection of poems, entitled Badal Jhukktay Pani Par. Poet Nazir Qaiser calls a "magical book". Dr Malik says that the motivation for this book came from Mazhar Tirmazi.

About the future of ghazal, Dr Malik says: "Whatever you may feel, neither ghazal nor nazm can die as long as there is even a single creator left who writes good poetry. Even one lone line can strike you."

On the overarching mood of his poetry, he says he realised that he missed something: "Apparently I had many things but a kind of sadness (dukh), that loss would always prevail. Sadness is part of the game. It has its own beauty. Personally I think it’s bigger than happiness. It gives you the value of happiness and the opportunity to know yourself. Separation (hijr) is alive and induces courage. But life is about moving on. It’s not a regressive memory…And statement-oriented poetry? Never. I feel like am sitting on a rostrum. This I don’t appreciate!"

"We have to have a commitment in medical practice and be sure of things. But the beauty of art is that there is no single way. Come this way and go there. Free your senses, you can talk and have full freedom," Dr Malik concludes.